- My Favorite Book of the Year

- The Year’s Biggest Disappointment

- Film Books

- Fiction

- Graphic Novels

- Reprints

- Etcetera

Here, in the early days of 2021, is the latest edition of my annual Bedlam in Print overview. As always, I’ll be exploring the good and not-so-good books I read over the previous year, as well as several worthy publications from the year before that (2019) that I missed, and some recommended upcoming releases.

This BiP differs from its predecessors in one major respect: it’s much longer than nearly any of the others. Clearly I had more time to read books in 2020 than in previous years, the reasons for which should be pretty obvious (and I certainly wasn’t alone, as print book sales increased by a reported 8.2 percent from those of last year). So let’s not waste any more time with this preamble and get to the overview, starting with…

My Favorite Book of the Year

That would be THE BROOD (PS Publishing), a 662 page “forensic and holistic” study of David Cronenberg’s THE BROOD that is, quite simply, the most thorough and wide-ranging analysis of a horror movie that’s ever been put to paper. It was penned by the famed comic book artist, editor and film commentator STEPHEN R. BISSETTE, an author who works best in large doses.

That would be THE BROOD (PS Publishing), a 662 page “forensic and holistic” study of David Cronenberg’s THE BROOD that is, quite simply, the most thorough and wide-ranging analysis of a horror movie that’s ever been put to paper. It was penned by the famed comic book artist, editor and film commentator STEPHEN R. BISSETTE, an author who works best in large doses.

THE BROOD, released in 1979, was the depraved account of a man discovering that his estranged wife is creating a brood of inhuman creatures who enact her darkest impulses. It was Cronenberg’s fourth feature, and apparently his “first masterpiece.” Bissette makes a persuasive case for THE BROOD’S greatness, although it seems to me that the film described here is closer to what Cronenberg wanted to make than what resulted.

The film’s creation and reception are explored at great length in these pages, which can literally be said to leave no BROOD-related stone unturned. This entails a wealth of footnote packed digressions; as Bissette warns early on, “This text may wander afield at times, but stay with me: it always comes back to THE BROOD, with a purpose.”

Also included are interviews with the film’s star Art Hindle, his onscreen daughter Cindy Hinds, novelist Graham Masterton and cinematographer Mark Irwin. Conspicuously absent from the line-up is David Cronenberg, who Bissette admits in the acknowledgements page will “most likely never read this book.” I hope Mr. Cronenberg reverses that stance, as I believe he’ll appreciate Bissette’s thoroughness and erudition. I certainly did.

Bissette’s was but one of quite a few film-related books I read in 2020, but before getting to the rest I’ll have to, having just revealed my favorite book of 2020, veer to the opposite category…

The Year’s Biggest Disappointment

That, I’m afraid, would be THE LIVING DEAD (Tor) by GEORGE A. ROMERO and DANIEL KRAUS. Clocking in at nearly 700 densely packed  pages, it seeks to be nothing less than the zombie novel to end all zombie novels, with a scope that Romero was never able to achieve in his films. Such ambition is laudable, but also foolhardy.

pages, it seeks to be nothing less than the zombie novel to end all zombie novels, with a scope that Romero was never able to achieve in his films. Such ambition is laudable, but also foolhardy.

A lengthy afterword by Kraus fills us in on the travails he faced in putting together this novel. Romero apparently completed less than half of it before he died, but left behind detailed notes about the remainder of the book, as well as 100 pages of an unfinished novel and a short story. With so many disparate sources mixed in, it’s no surprise that THE LIVING DEAD is a choppy and discordant reading experience, suffering from an excess of principal characters alive, dead and undead.

Another problem is that, simply, all this has been done before. See Romero’s six films on the subject, as well as WORLD WAR Z, THE WALKING DEAD and innumerable other examples of zombie-themed media. Twenty years ago THE LIVING DEAD may indeed have been the genre landmark it so desperately wants to be, but right now it comes off as a well-intentioned but late-to-the-party addendum.

And now, with that out of the way, let’s get back to my favored category…

Film Books

We’ll start this category with my second favorite book of 2020: ERASERHEAD, THE DAVID LYNCH FILES Volume 1 (BearManor Media). Included are author KENNETH GEORGE GODWIN’s articles “ERASERHEAD: An Appreciation” and “The Making of ERASERHEAD,” which provide an analysis and production history of Lynch’s classic 1976 film, and the 1981 interviews with Lynch and his collaborators that Godwin used as research.

We’ll start this category with my second favorite book of 2020: ERASERHEAD, THE DAVID LYNCH FILES Volume 1 (BearManor Media). Included are author KENNETH GEORGE GODWIN’s articles “ERASERHEAD: An Appreciation” and “The Making of ERASERHEAD,” which provide an analysis and production history of Lynch’s classic 1976 film, and the 1981 interviews with Lynch and his collaborators that Godwin used as research.

“ERASERHEAD: An Appreciation” offers an intelligent reading of this notoriously abstract and (seemingly) impenetrable film. The focus is on sexuality, which Godwin claims is manifested most blatantly in the form of the mutant baby that powers the film. “The Making of ERASERHEAD” provides an in-depth look at the film’s five year gestation, with the film having begun as an AFI student project and growing into the mini-epic it became through the dogged efforts of Lynch, his lead actor Jack Nance and the crew.

The interview section of this book is something else entirely. In contrast to the polished and articulate sheen of the two articles, these interviews are somewhat raggedy. Godwin transcribes the chats verbatim, without editing or condensation, and that decision, IMO, was the correct one.

KENNETH GEORGE GODWIN and BearManor also provided DUNE, THE DAVID LYNCH FILES Volume 2 in 2020, focusing on Lynch’s 1984 filming of Frank Herbert’s DUNE. That film was of course one of the biggest cinematic follies of the eighties, and Godwin was handpicked by Lynch to document its Mexico City based shoot. The video footage created by Godwin didn’t survive (having apparently been destroyed by Universal), but the diary entries he kept throughout DUNE’S six month shoot did.

Those diaries are reproduced here, providing a concise rendering of how this mega-production went wrong. Godwin’s was a tiny part of a massive whole, but the travails he experienced showcase a mismanagement that started at the top and worked its way outward. As the DUNE shoot wound on morale steadily plummeted, resulting in defecting crewmembers, substandard special effects and widespread fears that the finished film might wind up “incoherent” and “quite simply, dull,” two things that did indeed come to pass.

THE BIG GOODBYE: CHINATOWN AND THE LAST YEARS OF HOLLYWOOD (Flatiron Books) by SAM WASSON is ostensibly about the making of CHINATOWN (1974), but its true concerns are Hollywood in the early 1970s and one of that milieu’s most contentious figures: Roman Polanski. The book’s Polanski-centric bent announces itself in the opening chapter, which fills us in the man’s Nazi-scarred background, his courtship of and marriage to Sharon Tate, and her brutal murder by members of the Manson family.

With regards to CHINATOWN, Polanski was instrumental in rewriting an extremely messy script, paring it down to what has been proclaimed the greatest screenplay ever written. Another pivotal collaborator was screenwriter Robert Towne’s little-known partner Edward Taylor, who worked quite extensively on CHINATOWN, as he apparently did on all of Towne’s scripts, yet never received any screen credit.

Wasson also explores CHINATOWN’s aftermath, during which Hollywood transformed from the classy business it was to the high concept-driven endeavor it became. I was a bit irritated by the author’s constant attempts at delineating the psychological states of his subjects, which aren’t always particularly convincing. But THE BIG GOODBYE is worth reading, being a (mostly) strong biography of an authentic masterpiece of American cinema, and a provocative depiction of the passions and crimes of one Roman Polanski.

Another iconic movie making-of book from 2020 was MADE MEN (Hanover Square Press) by GLENN KENNY, which explores one of the greatest films of our age: Martin Scorsese’s 1990 gangster epic GOODFELLAS. The picture painted by MADE MEN is a thorough one, answering most every question one could think to ask about GOODFELLAS and its creators. Included are copious interviews with nearly all the actors and technicians, a scene-by-scene breakdown of the film and some astute critical analysis.

Another iconic movie making-of book from 2020 was MADE MEN (Hanover Square Press) by GLENN KENNY, which explores one of the greatest films of our age: Martin Scorsese’s 1990 gangster epic GOODFELLAS. The picture painted by MADE MEN is a thorough one, answering most every question one could think to ask about GOODFELLAS and its creators. Included are copious interviews with nearly all the actors and technicians, a scene-by-scene breakdown of the film and some astute critical analysis.

Attesting to the thoroughness of Mr. Kenny’s approach, we also get a lengthy analysis of all the famous rock ‘n’ roll tunes played in the film (which makes for quite a list) and how they relate to the images they accompany.

ALRIGHT, ALRIGHT, ALRIGHT (HarperCollins) by MELISSA MAERZ explores Richard Linklater’s 1993 film DAZED AND CONFUSED in the form of an oral history. Depicting what occurs on the night of the last day of an Austin, TX high school in 1976, the film is a vast, unruly spectacle that also happens to be an unusually thoughtful and observant portrait of adolescence.

Linklater managed to make a staunchly personal, quirky film with big studio resources, and a cast that included Matthew McConaughey, Ben Affleck, Rene Zellwegger and Parker Posey. That achievement didn’t come about without a great deal of struggle by Linklater, who had to fight clueless studio heads at every turn, whereas the exploits of Linklater’s young cast were decidedly less fraught—with, according to their own recollections, drinking, pot smoking and hooking up being the order of the day.

Maerz also explores what occurred in the years after the film’s release. Actor Rory Cochrane asserts that “it’s a complete nostalgia movie,” although the nostalgia the film evokes is not for the 1970s, but rather the time in which DAZED was made. Anyone doubting that the early 1990s were a golden age for cinema need only view DAZED AND CONFUSED or read this book—or, better yet, do both.

Far, far down the quality scale from CHINATOWN, GOODFELLAS and DAZED AND CONFUSED is GRIZZLY II: REVENGE, whose making is  covered in SWIMMING AMONG SHARKS—THE STORY BEHIND THE MAKING OF GRIZZLY II: REVENGE (GBGB International) by the film’s producer SUZANNE C. NAGY. GRIZZLY II was a modestly conceived Hungarian made sequel (to the 1976 JAWS wannabe GRIZZLY) that wound up becoming one of the most monumental film shoots in its nation’s history.

covered in SWIMMING AMONG SHARKS—THE STORY BEHIND THE MAKING OF GRIZZLY II: REVENGE (GBGB International) by the film’s producer SUZANNE C. NAGY. GRIZZLY II was a modestly conceived Hungarian made sequel (to the 1976 JAWS wannabe GRIZZLY) that wound up becoming one of the most monumental film shoots in its nation’s history.

That English is not Nagy’s native language is evident in prose that appears to have been the result of Google translate (sample: “Contrary from the past when the American editor from 1987 wanted to bring in a new line in the story”). It’s worth slogging through for the story it relates, with Nagy having to contend with an inexperienced director, paranoid Soviet authorities, a constantly rewritten script, an incompetent editor and expulsion from the socialist-run Hungarian film industry.

The “good” news is that in 2020 GRIZZLY II was finally completed and unleashed upon an all-too-suspecting public, with Nagy boasting of learning an important lesson: “we all have to stick to important things in our life, which is the highest level of achievement.” That depends, obviously, on one’s definition of “important.”

CHASING THE LIGHT (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) is a memoir by filmmaking legend OLIVER STONE. It’s a good book whose biggest drawback is that it only covers a portion of its subject’s life, specifically the years from his birth to the release of PLATOON. That Mr. Stone is a skilled writer is evident in his descriptions of his early years, in which the focus is kept where it should be: on the relationship between his stockbroker father and French immigrant mother, whose divorce when Stone was a teenager inspired a vision quest of sorts that led to him joining the US Infantry to “take part in this war of my generation.”

Of Stone’s early filmmaking experiences, this book devotes the most ink to SALVADOR (1985). Its calamitous shoot is detailed quite extensively, with perilous south-of-the-border shooting conditions, a temperamental star and a painfully low budget all taking their toll.

The book ends on a rather ominous note, with Stone claiming of his 1980s-era self that “Thirty years now, I look back and realize I had no idea then of the storm that was coming.” Let’s hope Oliver Stone has a follow-up volume in the works, as I’d very much like to get his take on that storm.

APROPOS OF NOTHING (Arcade Publishing) is the autobiography of WOODY ALLEN, who not too long ago he was considered the epitome of class in Hollywood but is now a pariah. The Woody Allen unveiled in these pages is very much in keeping with the lovable schlemiel persona he’s cultivated over the decades; if his jokey recollections are to be believed, his success was due mostly to luck and circumstance. Of the films for which he’s become famous, Allen is similarly deprecating: “while some are entertaining, no idea I ever had is going to start any new religion.”

APROPOS OF NOTHING (Arcade Publishing) is the autobiography of WOODY ALLEN, who not too long ago he was considered the epitome of class in Hollywood but is now a pariah. The Woody Allen unveiled in these pages is very much in keeping with the lovable schlemiel persona he’s cultivated over the decades; if his jokey recollections are to be believed, his success was due mostly to luck and circumstance. Of the films for which he’s become famous, Allen is similarly deprecating: “while some are entertaining, no idea I ever had is going to start any new religion.”

Thus it’s all the more jarring when the tone changes in the final hundred pages, in which things turn very serious indeed. They detail Allen’s affair with GF Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter Soon-Yi Previn, with he leaving X-rated Polaroid pics of these lovebirds in plain sight of Soon-Yi’s mother. Allen’s explanation for that is simple short-sightedness, or “simply a blunder by a klutz. Sometimes, a cigar is just a blunder by a klutz.” This led to allegations of child molestation that continue to dog him.

Of Allen’s legendary sexual appetite we learn very little (he’s partial to the term “make love”), nor the particulars of his relationships with Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein, who are both mentioned here, but only briefly. This book may tell the story of Woody Allen, but it doesn’t tell the whole story by any means.

CONCLUSIONS (Faber & Faber) is the second of two memoirs by the acclaimed British filmmaker JOHN BOORMAN. His former memoir, ADVENTURES OF A SUBURBAN BOY, only went up to 1991, and in the appropriately titled CONCLUSIONS the eightyish Boorman gives his thoughts on what occurred in the ensuing years. Boorman’s advanced age likely accounts for the book’s rambling nature, incorporating as it does straight autobiography, poetry, drawings, lessons on filmmaking and a great deal of recycled material from the previous book. CONCLUSIONS, then, is not an entirely satisfying read, but I suspect that makes little difference to the soon-to-be-late Boorman.

BARRY SONNENFELD, CALL YOUR MOTHER: MEMOIRS OF A NEUROTIC FILMMAKER (Hatchette Book Group, Inc.) was written by BARRY  SONNENFELD, a cinematographer-turned-director whose defining trait, it seems, is self-deprecation. This, his autobiography, is very much in keeping with the life story Sonnenfeld tends to put forth in interviews: that of a happy-go-lucky moron who happened to stumble into making movies.

SONNENFELD, a cinematographer-turned-director whose defining trait, it seems, is self-deprecation. This, his autobiography, is very much in keeping with the life story Sonnenfeld tends to put forth in interviews: that of a happy-go-lucky moron who happened to stumble into making movies.

Of course, Sonnenfeld’s self-mockery masks some decidedly unpleasant childhood memories. Most of them center on an individual referred to as Cousin Mike the Child Molester, or “CM the CM,” whose outrages were so horrific that Sonnenfeld doesn’t appear to entirely know how to deal with them.

So focused is Sonnenfeld on relating childhood anecdotes that the book’s primary reason for being—his cinematic output—isn’t nearly as robust as one would expect. Of the “profoundly painful experience” of directing MEN IN BLACK 3, for example, all he reveals is the promise that “someday I might write about it.” But apparently not now.

I’M YOUR HUCKLEBERRY (Simon & Schuster) is a memoir by movie star VAL KILMER. He can be a great actor on occasion (as in THE DOORS and TOMBSTONE), but the majority of Kilmer’s roles, and the movies they grace, are unmemorable. It certainly doesn’t help matters that, as he acknowledges in these pages, Kilmer has a reputation in Hollywood for being an irrepressible pain in the ass.

His story is related in a voice that’s exactly as you’d expect. Beginning with the words “Dear Reader, I have a crush on you,” the book weaves in snatches of poetry, magic realism and a great deal of proselytizing about the glories of Christian Science, the religion in which he was raised.

Kilmer is not hesitant to take full credit for the success of certain movies in which he appeared (he claims he once told a producer that “If you want, I’ll stop making the film better”), and unafraid to let his pretentions take center stage (he says Batman “could be a character out of Ovid’s METAMORPHOSES”). He is, as they say, a character, and this book appears to reflect his mercurial personality quite well—something that, depending on your point of view, you can take as either a recommendation or a warning.

In 2020 a most unexpected treat for film nerds appeared in the form of THE LONG LOST AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF GEORGES MELIES (georgesmelies.co.uk), the premiere English language translation of the autobiography of GEORGES MELIES (1861-1938), the legendary illusionist and film director, with additional material by JON SPIRA.

In 2020 a most unexpected treat for film nerds appeared in the form of THE LONG LOST AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF GEORGES MELIES (georgesmelies.co.uk), the premiere English language translation of the autobiography of GEORGES MELIES (1861-1938), the legendary illusionist and film director, with additional material by JON SPIRA.

Written, bizarrely, in the third person, this memoir is a short recounting printed in extremely large text, alongside detailed annotations by Spira. Those annotations are necessary to correct the many inaccurate claims made by Méliès, who’s given to self-aggrandization that borders on braggadocio. This is nonetheless an excellent summation of his life, taking us through its high points around the turn of the Twentieth Century and the many filmic innovations he introduced, to the financial problems that overwhelmed him, to his happy (or so he claims) final years.

Also included is a Méliès penned manual for prospective filmmakers entitled “Cinematic Views” and a biography of Méliès’s little known documentary filmmaker brother. Rounding things out are interviews with Méliès enthusiast and restorer Serge Bromberg, BFI silent film curator Bryony Dixon and filmmaker Michel Gondry.

Another filmic autobiography from 2020 was MY FILMS WITH CARMELO BENE (Damocle) by MARIO MASINI, consisting of about thirty pages of text printed in Italian, English and French.

A true iconoclast, Carmelo Bene was an actor, playwright, novelist and filmmaker who in his films (as in his life) favored the ridiculous, the outlandish and the extreme. Mario Masini, the cinematographer on four of Bene’s five feature films, claims to have first met Bene in 1967. The two apparently developed a mental bond that proved quite useful given that Bene worked without a script and was a compulsive improviser.

A longer and more detailed treatment would have been preferable, but Masini provides a good overview of his Bene collaborations, and some fun tidbits. Among the latter are the revelation that the filming of DON GIOVANNI (1970) took place entirely in Bene’s tiny apartment, and that a tampon “spurting out” of a naked extra ruined a shot in SALOME (1972). In closing Masini states, quite persuasively, that “We need to get back our sense of irony, to get back our sense of sarcasm, and to get back to making fools of ourselves. In short, we need someone like Carmelo.”

Moving away from the memoirs, let’s take a look at THE CANNON FILM GUIDE Volume 1 (BearManor Media) by AUSTIN TRUNICK, a 527 page  study that is either a standout example of gonzo scholarship or an extended manifestation of unfiltered insanity. Either way I’m glad the book exists, as it’s as gloriously obsessive a study of the late, notorious Cannon Films as any eighties movie buff could possibly desire.

study that is either a standout example of gonzo scholarship or an extended manifestation of unfiltered insanity. Either way I’m glad the book exists, as it’s as gloriously obsessive a study of the late, notorious Cannon Films as any eighties movie buff could possibly desire.

Cannon was an exploitation movie outfit purchased in 1979 by the Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus. They went on to turn Cannon into a mini-powerhouse that boldly intermixed trash and prestige. This book, the first of a three volume whole, covers the early years of Cannon’s output, which was heavy on the trash part of the equation.

All of Cannon’s major releases from the years 1980-84 are profiled. Included are well-known hits like ENTER THE NINJA, DEATH WISH II, BREAKIN’ and MISSING IN ACTION, as well as more obscure entries like TEEN MOTHERS, NANA and THE SECRET OF YOLANDA. Each has a detailed backstory and production history, laid out by Trunick in a voluminously researched and reader-friendly manner that’s not without a great deal of humor. An absolute must!

Fiction

Disappointing though THE LIVING DEAD was, I quite enjoyed another 2020 debut novel by a prominent genre filmmaker: ARE SNAKES NECESSARY? (Hard Case Crime) by BRIAN DE PALMA and SUSAN LEHMAN. The novel contains at-times clumsy present tense prose that’s constantly telegraphing the fact that its authors view their story in visual rather than literary terms (in sentences like “The face she sees reflected in the guest-room mirror looks exhausted”), yet De Palma and Lehman’s ignorance of proper novelistic etiquette makes for something unique and interesting.

Inspired by the John Edwards sex scandal, it pivots on Barton Brock, a ruthless political campaign manager who instigates a twisted drama of sex, betrayal and murder with a suitably delirious Eiffel Tower set climax that’s pure De Palma. The narrative is consistently clever and unpredictable, with a couple of surprising twists (one of them quite perverse). It may be a bit over-reliant on coincidence, and a little too neat in its wrap-up, but overall ARE SNAKES NECESSARY? is terrifically nasty, sexy, disreputable fun.

Another successful director who published a novel in 2020 was TOM HOLLAND, the writer-director of movies like FRIGHT NIGHT and CHILD’S PLAY. THE NOTCH (Cemetery Dance) is the novel, and it’s an odd one.

Another successful director who published a novel in 2020 was TOM HOLLAND, the writer-director of movies like FRIGHT NIGHT and CHILD’S PLAY. THE NOTCH (Cemetery Dance) is the novel, and it’s an odd one.

Sprawling yet quite intimate in its scope, it relates what occurs over the course of two fateful days, during which an apparently autistic boy is discovered in a notch between two Arizona desert buttes. The boy, it quickly transpires, is able to heal wounds with the touch of a hand, which sets off a wave of madness that sees the boy come into contact with a band of gangbangers just as a deadly worldwide pandemic sweeps the land (rendering this a most appropriate 2020 release). At 478 pages the book is too long, but Holland amply demonstrates his skill for plotting and structure in short 2-4 page chapters, with prose that positively surges with forward momentum. THE NOTCH is, in short, a page-turner.

For an example of literary horror done right see TENDER IS THE FLESH (Pushkin Press) by AGUSTINA BAZTERRICA, about a future world where a mysterious disease has wiped out nearly all the world’s animals, resulting in the mass harvesting of human flesh for food.

That’s a metaphor, obviously, for modern man’s self-destructive tendencies, but Bazterrica does a thorough, non-satiric job constructing this dystopia. Laws are in place as to how the “special meat” of this society is to be handled and who is selected to supply it (societal outcasts, obviously), with the details of the meat production being disturbingly graphic. This is necessary to a book whose overall impression is that of a complacency-shattering kick in the gut. Good!

The novella LAST CASE AT A BAGGAGE AUCTION (Harper Day Books) by ERIC J. GUIGNARD has a set-up that is, as they say, a grabber. Set  in Detroit, circa 1963, it’s about Charlie, a compulsive hoarder who likes to bid on discarded items. His latest acquisition is an old suitcase that when opened reveals an antique gramophone player and some records to go with it. When those records are played they emit an eerie chanting that proves hypnotic, leading Charlie to investigate the origins of the suitcase and its unholy contents.

in Detroit, circa 1963, it’s about Charlie, a compulsive hoarder who likes to bid on discarded items. His latest acquisition is an old suitcase that when opened reveals an antique gramophone player and some records to go with it. When those records are played they emit an eerie chanting that proves hypnotic, leading Charlie to investigate the origins of the suitcase and its unholy contents.

I’ll refrain from revealing what Charlie’s investigations turn up, other than to say that they involve a historical personage whose addition to the book is as delightfully unexpected as it is menacing. The prose is smooth and uncluttered, in service of a consistently surprising narrative that’s packed with the type of thrills you’d expect from a scary book, along with a great deal of sumptuously researched historical detail.

ERIC J. GUIGNARD was also the driving force behind EXPLORING DARK FICTION #5: A PRIMER TO HAN SONG (Dark Moon Books). It contains six stories by Song, with commentary for each by Michael Arnzen.

What’s most striking about these stories—presented via excellent translations by Nathanial Isaacson—is their range. We’re informed that “Science Fiction” in China encompasses the fantastic in virtually every form, which explains the varied nature of Song’s fiction, including “Earth is Flat,” a quirky historical speculation; “The Wheel of Samsara,” which explores the quantum-verse; and “Two Small Birds,” a potent example of magic realism. Rounding things out are three novella-length tales: the surreal “Transformation Subway,” the horrific “Fear of Seeing” and the futuristic espionage thriller “My Country Does Not Dream.”

The book concludes with a detailed bibliography of Song’s publications, which is quite extensive. If this book’s contents are truly an indication of the quality of those publications, it’s clear we westerners have missed out on a great deal.

Another potent 2020 anthology was THE AGE OF DECAYED FUTURITY (Hippocampus Press) by MARK SAMUELS. Samuels’s tales drip with old world decadence, but have a modern and even somewhat futuristic air (as summed up by the title), being the logical evolution of the bent universe evoked by Lovecraft and Machen.

Another potent 2020 anthology was THE AGE OF DECAYED FUTURITY (Hippocampus Press) by MARK SAMUELS. Samuels’s tales drip with old world decadence, but have a modern and even somewhat futuristic air (as summed up by the title), being the logical evolution of the bent universe evoked by Lovecraft and Machen.

The Lovecraft connection is perhaps most evident in this book’s shortest tale “The Black Mould,” which can be viewed as a modern-day rewrite of “The Fungi from Yuggoth.” Other tales collected here include “Mannequins in Aspects of Terror,” about a profoundly creepy art exhibit, “Apartment 405,” involving a mysterious disappearance, sleepwalking and a strange mirror, and “The White Hands,” which concerns a solitary author and his apparently undead muse.

THE SPIDER MAN was a late-in-coming translation of the work of EDOGAWA RANPO (a name often rendered in English as “Rampo” but here given its correct spelling) from Zakuro Books. Initially published in 1929, THE SPIDER MAN is brainy and grotesque in equal measure, and never less than fully absorbing.

No, the novel has nothing to do with the Spiderman we know. Rather, it’s about a villain who, as the opening chapter informs us, “is named the Spider Man since just like the spider he is brutish and otherworldly.” This individual dons various disguises in order to kill unsuspecting women, with his overriding purpose revealed in the penultimate chapter.

Graphic Novels

One of the sickest surprises of 2020 was the release of MANIAC (Eibon Press), which breaks new ground in splatterific excess. It’s an adaptation of  the William Lustig directed 1980 movie of the same name, crossed with the 1982 Lucio Fulci slasher THE NEW YORK RIPPER. The adaptor was the always-inspired STEPHEN ROMANO, and the superbly rendered illustrations were by PAT CARBAJAL, whose respective labors are complimented by durable and attractive packaging.

the William Lustig directed 1980 movie of the same name, crossed with the 1982 Lucio Fulci slasher THE NEW YORK RIPPER. The adaptor was the always-inspired STEPHEN ROMANO, and the superbly rendered illustrations were by PAT CARBAJAL, whose respective labors are complimented by durable and attractive packaging.

As with many Eibon Press comics, MANIAC “stars” a number of real life performers impeccably rendered by Mr. Carbajal, among them Joe Spinnell and Caroline Munro. Spinnell plays Frank Zito, a serial killer bearing an unhealthy fixation on his deceased mother and a most unfortunate habit of dismembering prostitutes.

The nature of Frank’s insanity (and the book overall) is laid out at the very beginning, with an eye-popping two page spread depicting slashed throats, ripped-out hearts and exposed innards, and the proceedings only grow steadily nastier. The MANIAC film may be one of the most notorious gore fests of its era, but this book far outdoes it, and the equally controversial NEW YORK RIPPER, in a potent blast of no-frills nastiness.

The Argentine epic PERRAMUS: THE CITY AND OBLIVION by ALBERTO BRECCIA and JUAN SASTURAIN is an important release by Fantagraphics, who previously published a portion of it in 1991. Here they provide the entire saga in sturdy hardcover format.

It’s a strange and foreboding comic that interprets the horrific realities of the Argentine military dictatorship, during which over 15 thousand citizens “disappeared,” in a surreal and often absurd manner. The tale is driven by a band of machine gun wielding monsters with skull faces and overcoats. The protagonist is a harried man named Perramus who narrowly escapes a raid by the creatures, and winds up pursued by them through a variety of strange landscapes, with companions that include a quirky band of circus performers and the author Jorge Luis Borges.

The best thing about the project is the nightmarish artwork, rendered in magnificently skewed, expressionistic black and white. The story is often incoherent, although that’s probably due to the fact that, as has been claimed by Fantagraphics editor Robert Boyd, PERRAMUS contains allusions that can only be fully understood by residents of Argentina.

Reprints

The Jim Morton translated, Pop Void published MINE-HAHA, OR ON THE CORPORAL EDUCATION OF YOUNG GIRLS isn’t the first English version of FRANK WEDEKIND’s 1903 German language novella, but it is the most widely accessible.

The Jim Morton translated, Pop Void published MINE-HAHA, OR ON THE CORPORAL EDUCATION OF YOUNG GIRLS isn’t the first English version of FRANK WEDEKIND’s 1903 German language novella, but it is the most widely accessible.

The subject is a girls’ boarding school whose pupils are trained in how to be ladylike. This includes a great deal of strenuous exercise and forced marching, with a switch utilized to ensure that assignments are carried out correctly. There’s also a hushed-up drowning, a singularly bizarre play the girls perform and the protagonist’s coming of age, in which she goes from victim to perpetrator.

Prudish early Twentieth Century literary standards prevented Wedekind from exploring his overriding theme, of a young woman’s maturation in a male-dominated society, in too literal a fashion, but it shines through nonetheless. This brings us to perhaps the book’s most impressive aspect: its entirely convincing depiction of a woman’s point of view, making this a very rare example of male-essayed feminism done right.

CODE BLUE (Punk Hostage Press), originally published in 2014, is a novella by So Cal punk legend JACK GRISHAM. Grisham was the front man for T.S.O.L., whose 1981 ode to necrophilia “Code Blue” (sample lyric: “I creep on over to the mortuary/Lift up the casket and fiddle with the dead/Their cold blue flesh makes me turn red”) was the inspiration for this book, consisting of a darkly comedic short story with R. Crumb-esque black and white illustrations by Scott Archer.

It’s the story of James, a teenage punk who elects to visit the mortuary where the corpse of a deceased sex-mate is interred…and, based on the above-quoted song lyrics, I think you can figure out what he does next.

That Grisham’s specialty is music rather than fiction is evident in the halting and at times amateurish prose. But the near-poetic simplicity of the tale is salutary, as is Grisham’s talent for describing the indescribable. Yes, the descriptions of Jack’s final outrage are extremely graphic and detailed, and yes, this is strictly an adults-only tale.

Etcetera

I APPEARED TO THE MADONNA (Contra Mundum) is a memoir of sorts by the abovementioned CARMELO BENE. It covers most of the major  occurrences in Bene’s life, albeit in extremely unorthodox fashion, with Bene’s esoteric ruminations given prominence over factual detail—although precisely how much of what Bene details is “factual” remains an open question.

occurrences in Bene’s life, albeit in extremely unorthodox fashion, with Bene’s esoteric ruminations given prominence over factual detail—although precisely how much of what Bene details is “factual” remains an open question.

There’s also a 1995 “Autobiographical Portrait” that commences the book with a swirl of disjointed observations that seem closer to an extended prose poem, and so makes for a good introduction to what follows. It’s all illuminated by a sarcastic, self-mocking air that was a quintessential component of Bene’s stage and screen (and, evidently, literary) personas.

PULP HORROR: ALL REVIEWS SPECIAL EDITION (thepaperbackfanatic@sky.com; 2020) is an absolute must-have for literary horror buffs: a collection of over 130 reviews of vintage horror-themed publications, put together by paperback enthusiast JUSTIN MARRIOTT (of Pulp Horror magazine and other like-minded periodicals). The highs and lows of horror lit are explored, from Ramsey Campbell (whose ANCIENT IMAGES and THE GRUESOME BOOK are given admiring notices) to Guy N. Smith (represented by reviews of THE SUCKING PIT and THE FESTERING). Horror magazines are also brought up, as are comic anthologies and classics by H.P. Lovecraft and Richard Matheson.

Stylistically the reviews are a bit uneven, but such complaints were overridden by the eclectic nature of this book. It’s certainly the only place you’ll find the widely revered BOOK OF SKULLS by Robert Silverberg and the magazine tie-in version of the 1970s porno feature DRACULA SUCKS sharing the same space, and I say that’s a good thing.

2019: Books I Missed

Here’s a great idea, if you ask me: THE COLLECTED PULP HORROR (thepaperbackfanatic@sky.com), a single-volume collection of the first three issues of the JUSTIN MARRIOTT edited Pulp Horror magazine. Given that Marriott’s periodicals tend to go out of print extremely quickly, he’s done us a great service with this book (and the one listed above).

Here’s a great idea, if you ask me: THE COLLECTED PULP HORROR (thepaperbackfanatic@sky.com), a single-volume collection of the first three issues of the JUSTIN MARRIOTT edited Pulp Horror magazine. Given that Marriott’s periodicals tend to go out of print extremely quickly, he’s done us a great service with this book (and the one listed above).

As I’ve come to expect from Marriott, the contents are strong. Reviewed are classics like Fred Chappell’s DAGON, Gerald Kersh’s NIGHTSHADE AND DAMNATIONS, Sarban’s THE SOUND OF HIS HORN and Robert Stallman’s THE ORPHAN. Other goodies include interviews with the pulpmeisters Robert Lory and Guy N. Smith, an admiring profile of the late Charles Birkin and a learned take on Robert Heinlein’s PUPPET MASTERS.

THIRD INSTAR by DAVID GULLEN is a dreamy fantasy from Eibonvale Press, a tantalizing glimpse of a city located quite literally at the edge of the world. The protagonist is a petty grifter identified as Mazehew, who in the midst of a parade is attacked by a mob and tossed into a cauldron. In this enclosure he’s lowered down the side of a cliff in some kind of execution ritual, a descent that lasts for some time but u:ltimately leads to a “second life.”

This story, obviously, has real metaphoric significance, and adroitly straddles the borderline between dream and reality. Ultimately the author’s descriptive power and world building are what resonate most, with an impressive amount of incident and detail packed into just 54 pages, which conclude on an appropriately haunting note.

More fun from Eibonvale occurred in THE MAN WHO MURDERED HIS MUSE by JAMES CHAMPAGNE, a pleasingly eccentric horror novella. Set  in a convincingly delineated East Coast hipster milieu, it’s a depiction of old school decadence updated, quite ably, to 21st Century America.

in a convincingly delineated East Coast hipster milieu, it’s a depiction of old school decadence updated, quite ably, to 21st Century America.

The narrator is Hamsa Cauldron, a literarily inclined 19-year-old lesbian based in New England. There she meets Hector Teufel, a retired horror novelist. The two have a most interesting conversation in which he reveals that he was once a great success due to dabbles in mysticism, the nature of which is unveiled in the subsequent chapters.

THE MAN WHO MURDERED HIS MUSE won’t change the world, and could possibly have stood to be a bit longer (the ending is a tad abrupt), but taken on its own terms it’s an enormously clever and well-wrought little book. It may be the ultimate example of a neo-decadent tale, set in a very up-to-the-minute environ but with a distinctly old world flavor.

TOMORROW, WHEN I WAS YOUNG is another Eibonvale novella, a most peculiar fantasy by JULIE TRAVIS. It’s about a mortal woman named Zanders who finds herself aboard The Giantess, a ship making its way through a world that corresponds to our own but for the fact that life, death, past, present and future all co-exist.

Crucially, we’re thrown directly into the action on the Giantess, with the explanation for Zanders’ presence on it left open-ended until later on in the story. The traditional dream-reality narrative dynamic is inverted, with the surreality of the Giantess’s voyage assuming “normal” status and the details of Zanders’ former life presented as a “series of dreams.”

The closest antecedent I can think of is THE SANITORIUM UNDER THE SIGN OF THE HOURGLASS (both the Bruno Schultz novella and 1973 film adaptation), which also concerned a dream-region marked by a decidedly fluid sense of reality. Ultimately, though, TOMORROW, WHEN I WAS YOUNG is pretty unique, a potent example of freeform fantasy done right.

Yet more Eibonvale goodness can be found in THE UNEASY by ANDREW HOOK. It follows the exploits of Imogen, a British perfumer who moves to Paris. She arrives expecting it to live up to its reputation as the city of romance, but finds that Paris’s other major attribute, as the birthplace of surrealism, is more appropriate. Imogen desires a lover, but has very precise specifications: “a man as shadowy as he were dark, a doppelganger lover, who would cling in adulation and respect but who would not exist without her allowance of existence.”

Yet more Eibonvale goodness can be found in THE UNEASY by ANDREW HOOK. It follows the exploits of Imogen, a British perfumer who moves to Paris. She arrives expecting it to live up to its reputation as the city of romance, but finds that Paris’s other major attribute, as the birthplace of surrealism, is more appropriate. Imogen desires a lover, but has very precise specifications: “a man as shadowy as he were dark, a doppelganger lover, who would cling in adulation and respect but who would not exist without her allowance of existence.”

Imogen’s minutely described reveries are quite carnal in nature, involving bird mask wearing men whose “penises swirled like guy ropes in a sea breeze” and a climactic coupling that involves a “gradual suicide into a faction of normalcy.” I strongly believe that Andre Breton and his cohorts, who were partial to darkness and unreality, would have approved.

2019 contained a Zakuro Books published translation of the work of EDOGAWA RANPO: POMEGRANATE AND THE DEVOURING INSECTS, two previously untranslated stories. “Pomegranate,” initially published in 1934, and “The Devouring Insects,” from 1929, represent the two extremes of Ranpo’s early fiction. This means the first is a straight detective story while the second reminds us quite forcefully that Ranpo was the father of Japan’s “ero-guro” (erotic-grotesque nonsense) genre.

In “Pomegranate” a police detective relates the particulars of the Case of the Acid Murderer, involving the discovery of a man’s acid-scarred corpse and the investigation into said man’s death. The story overall is a strong one, with prose that’s thoroughly redolent of early twentieth century pulp fiction, down to the leering yet restrained descriptions.

“The Devouring Insects” is much simpler. It’s about Masaki Aizou, a psychotically introverted loner who becomes romantically obsessed with Fuyuo Kinoshita, a beautiful former schoolmate. This leads to staking, voyeurism and, eventually, a complete psychotic break, with Masaki murdering Fuyuo and taking her corpse back to his home. Ranpo, you can be sure, describes the corpse’s decomposition in loving detail, and also Masaki’s concluding act of (implied) necrophilia.

SEVEN DAYS (Simon & Schuster), initially published in 2001, was the second English language thriller by Quebec’s PATRICK SENECAL. Hugely  popular in his native land, Senecal deserves to be better known in ours—although SEVEN DAYS probably isn’t the best place to start.

popular in his native land, Senecal deserves to be better known in ours—although SEVEN DAYS probably isn’t the best place to start.

It pivots on Bruno Hamel, a contented surgeon whose life is shattered by the torture-murder of his young daughter. It doesn’t take the police long to track down the perpetrator, who Bruno becomes determined to make pay for his crimes by kidnapping “the monster” from police custody and subjecting him to a seven day torture-thon.

A great deal of inventive grotesquerie is detailed in these pages, as are moral implications that are provocative, to say the least. Decidedly less edifying are the abundance of clichés, implausibilities and purple prose (“He was saving his emotions for later…when hate and joy would be joined in a most devastating marriage”). Senecal knows how to spin a gripping and thought-provoking yarn, but I wish that in this particular case the raw material was a bit stronger.

More film books were in the offing in 2019, including MY BEST FRIEND’S BIRTHDAY: THE MAKING OF A QUENTIN TARANTINO FILM (BearManor Media) by ANDREW J. RAUSCH. Detailed is a late 1980s no-budget feature directed by a young Quentin Tarantino. Another point of interest—for me at least—is the fact that the film was made during Tarantino’s employment at Southern California’s late Video Archives, an establishment I used to frequent that served as a primary filming location for MY BEST FRIEND’S BIRTHDAY.

The film is a scrappy and amateurish black and white comedy that currently exists in an incomplete compilation. Included in this book are recollections from a number of the players in the MY BEST FRIEND’S BIRTHDAY saga, including co-creator Craig Hamann, producer Roger Avary, lead actress Crystal Shaw and Tarantino himself. Overall I feel the book is indispensable, not just for Tarantino fans but for anyone curious about the gritty realities of DIY moviemaking.

RIDLEY SCOTT: A BIOGRAPHY (University Press of Kentucky) isn’t what I’d call revelatory. The book is, in fact, a surface-level exercise that never delves too deeply into the attitudes or proclivities of filmmaker Ridley Scott, leaving us with a subject who was and remains something of an enigma.

RIDLEY SCOTT: A BIOGRAPHY (University Press of Kentucky) isn’t what I’d call revelatory. The book is, in fact, a surface-level exercise that never delves too deeply into the attitudes or proclivities of filmmaker Ridley Scott, leaving us with a subject who was and remains something of an enigma.

Author VINCENT LoBRUTTO takes us through Scott’s life, starting with his WWII scarred childhood in Northeast England. From there Scott rose to become a prolific director of TV commercials, creating his own advertising firm and, starting with THE DUELLISTS (1977), attained success as a director of feature films, with ALIEN, BLADE RUNNER, GLADIATOR and THE MARTIAN among his credits.

LoBrutto, as with his biographies of Stanley Kubrick and Martin Scorsese, is a bit too fawning toward his subject. He vastly overpraises Scott disasters like MATCHSTICK MEN (noting its “deft comic touch” and “lively pace”) and ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD (apparently a “Stylish and grueling thriller”), while in those Scott films the author can’t bring himself to defend someone else usually takes the blame. Of Scott’s personal life only the most perfunctory details are included, although in LoBrutto’s defense, Scott has never seemed too interested in letting the public in on more than that, making a fully-rounded biographical portrait difficult if not impossible.

While on the subject, let’s turn to TONY SCOTT: A FILMMAKER ON FIRE (McFarland & Company, Inc.) by LARRY TAYLOR, a must-read by default. It’s certainly not the ideal biography of Ridley Scott’s late brother Tony (1944-2012), but it is currently the only one.

Few other filmmakers had such a skilled and assured facility for kinetic moviemaking as Tony Scott. His is a solid and exciting filmography, from the arty horror fest THE HUNGER to TOP GUN, which provided the first glimpse of the glitzy commercialism that would become his trademark. Yet Scott was also careful to keep an eye on things like structure, characterization and authenticity.

Constructing his account from previously published interviews, profiles and reviews, Taylor provides a lively but only partially satisfying overview of Scott’s career. I’ll confess I was hoping for something in the way of an explanation for Scott’s 2012 suicide, but Taylor, perhaps understandably, has none to offer.

Looking Forward

BEAUTIFUL STAR by YUKIO MISHIMA

The long-awaited English translation of Yukio Mishima’s 1962 Japanese language sci-fi novel UTSUKUSHII HOSHI, the basis for the similarly monikered 2017 film.

CINEMA SPECULATION by QUENTIN TARANTINO

A nonfiction book by Tarantino, described as a “deep dive into the movies of the 1970’s, a rich mix of essays, reviews, personal writing, and tantalizing what-if’s,” incorporating, presumably, the now-defunct “Tarantino’s Reviews” section of the New Beverly Cinema website.

DANGEROUS VISIONS AND NEW WORLDS edited by ANDREW NETTE, IAN McINTYRE

Subtitled “Radical Science Fiction 1950-1985,” this is an overview of the new wave sci fi book scene that follows STICKING IT TO THE MAN and GIRL GANGS, BIKER BOYS AND REAL COOL CATS, both of which come highly recommended.

ECHO by THOMAS OLDE HEUVELT

ECHO by THOMAS OLDE HEUVELT

A new novel from the author of HEX, ECHO is “a harrowing novel of obsession and the destructive force of nature” about “A mountain climber wakes from a coma after a devastating accident in the Swiss Alps…and finds something terrifying has awakened inside of him.”

THE MAN WITH KALEIDOSCOPE EYES by TIM LUCAS

A novel based on the famous unfilmed screenplay by Tim Lucas and Charlie Largent (Joe Dante, FYI, was supposed to direct the film, and Quentin Tarantino was at one point set to star) about the making of Roger Corman’s THE TRIP.

NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI by CARMELO BENE

The long-in-coming English translation of Bene’s Italian language novel, the inspiration for the infamous 1968 film.

NOTHING BUT BLACKENED TEETH By CASSANDRA KHAW

A great deal of pre-release praise has greeted this horror novella, scheduled to be released in October. It’s said to involve a haunted house, and set down in poetic prose that’s steeped in Japanese folklore.

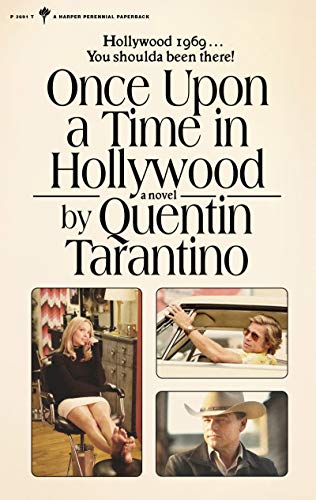

ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD by QUENTIN TARANTINO

From Tarantino’s press release: “as a movie-novelization aficionado, I’m proud to announce my contribution to this often marginalized, yet beloved sub-genre in literature.”

POTSDAMER PLATZ; OR, THE NIGHTS OF THE NEW MESSIAH by CURT CORRINTH

The premiere English translation of a novel first published in German in 1919 that claims to “preach the sexual orgy as a means to salvation and universal copulation as a new world religion.”

SILENT MOVIE by PATRICK SENECAL

The third English publication of the work of Quebec’s Patrick Senecal, a translation of Senecal’s first novel 5150 RUE DES ORMES (adapted for film in 2009).