By GEORGES MELIES, JON SPIRA (georgesmelies.co.uk; 2020)

By GEORGES MELIES, JON SPIRA (georgesmelies.co.uk; 2020)

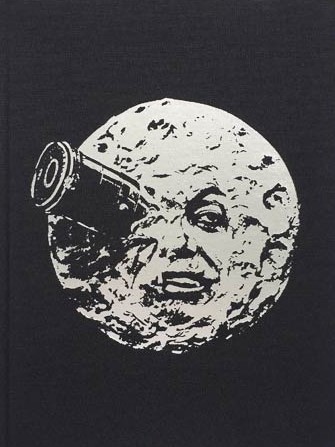

Possibly the most important film book of 2020, and one that fills a longtime void in silent film studies. This is the premiere English language translation of the autobiography of Georges Méliès (1861-1938), the legendary illusionist and film director. It’s certainly no exaggeration to state that Méliès revolutionized the art of filmmaking, being the inventor of filmic special effects and the creator of one of the most iconic images in cinema history: that of the rocket crashing into the eye of the man in the moon (which adorns the cover of this book).

The autobiography that makes up the bulk of this volume was taken from a limited edition 1945 French language book on Méliès. Entitled “Mes Memories” and written, bizarrely, in the third person, the memoir was included as a thirty page addendum to the book that author-filmmaker Jon Spira, upon discovering a copy, concluded would be of interest to English speaking cinema lovers. He was right.

Being as short as it is, Méliès’s recounting is printed in extremely large text, alongside detailed annotations by Spira. Those annotations are necessary not merely as filler, but to correct the many inaccurate claims made by Méliès, who’s given to self-aggrandization that borders on braggadocio (he unhesitatingly proclaims his “unrivaled place in the history of cinematography” and “astonishing and even unique career”). This is nonetheless an excellent summation of his life, taking us through its high points around the turn of the Twentieth Century, during the “first infant steps of cinematography” and the many innovations introduced by Méliès, to the financial problems that overwhelmed him and led to the destruction of the negatives of his films, to his happy (or so he claims) final years, when Méliès’s films gained a newfound popularity.

What’s lacking in this overview is detailed information on those films. Méliès’s astonishingly varied filmography, a full rendering of which is contained here, includes classics like THE CONQUEST OF THE POLE/A LA CONQUETE DU POLE and A TRIP TO THE MOON/LA VOYAGE DANS LA LUNE (the source of the aforementioned rocket-crashing-into-the-eye image), and a more detailed account of their making would have been welcome.

Also included is a Méliès penned manual for prospective filmmakers entitled “Cinematic Views” and a biography of Méliès’s brother Gaston, whose life story, Spira argues, was “far, far more exciting” than that of his more celebrated sibling. It involved a lengthy sojourn in the US, where during the years 1910-12 Gaston helped popularize the western film, followed by a grand sea voyage in the South Seas, in which Gaston Méliès made a number of pioneering documentaries that apparently no longer exist.

Rounding things out are interviews with Méliès enthusiast and restorer Serge Bromberg, BFI silent film curator Bryony Dixon and filmmaker Michel Gondry. The first two, at least, are quite informative about Méliès and the early days of cinema (whereas Gondry speaks more about 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY than he does the subject at hand).

Whatever issues I might have with its contents, I can’t fault the design of this book. It’s a sturdy, good-looking hardcover with classy pen-and-ink illustrations by Lucy Collins, although the expected stills from Méliès’s films are in shockingly short supply.