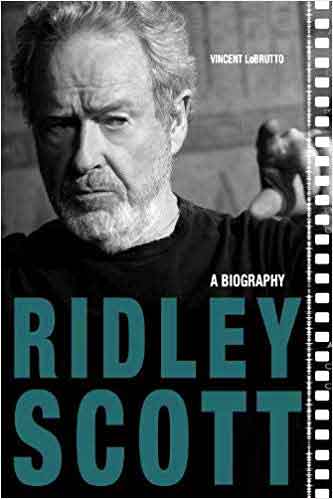

By VINCENT LoBRUTTO (University Press of Kentucky; 2019)

By VINCENT LoBRUTTO (University Press of Kentucky; 2019)

A book about the prolific British filmmaker Ridley Scott that isn’t what I’d call revelatory. RIDLEY SCOTT: A BIOGRAPHY is, in fact, very much a surface-level exercise that never delves too deeply into Scott’s attitudes or proclivities, leaving us with a subject who was and remains something of an enigma.

…a surface-level exercise that never delves too deeply into Scott’s attitudes or proclivities, leaving us with a subject who was and remains something of an enigma.

Author Vincent LoBrutto takes us through Scott’s life, starting with his WWII scarred childhood in Northeast England. From there Scott rose to become a prolific director of TV commercials, creating his own advertising firm that employed his younger brother Tony.

Scott’s feature filmmaking debut was THE DUELLISTS (1977), a low budget Joseph Conrad adaptation (this from a director who, as LoBrutto repeatedly notes, dislikes Conrad), followed in 1979 by the shouldn’t-need-any-introduction ALIEN (despite the fact that Scott apparently doesn’t like science fiction much more than he does Conrad). Both films showcased Scott’s overriding passion and obsession as a filmmaker: light and all its properties, something which Scott, as LoBrutto readily acknowledges, has been roundly criticized for emphasizing over things like plot and characterization.

From there followed BLADE RUNNER, which took Scott’s visual brilliance to new heights and, in conjunction with his justly famous 1983 Apple Macintosh commercial, established him as one of the world’s top filmmakers. His subsequent output, alas, has been quite uneven, marked by several hits (THELMA AND LOUISE, GLADIATOR, BLACK HAWK DOWN, THE MARTIAN), some interesting failures (LEGEND, SOMEONE TO WATCH OVER ME, 1492: CONQUEST OF PARADISE) and a number of outright duds (WHITE SQUALL, BODY OF LIES, THE COUNSELLOR, EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS).

LoBrutto, as was the case with his biographies of Stanley Kubrick and Martin Scorsese, is a bit too fawning toward his subject. He vastly overpraises Scott disasters like MATCHSTICK MEN (noting its “deft comic touch” and “lively pace”) and ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD (apparently a “Stylish and grueling thriller” that “holds a special place in the Ridley Scott oeuvre”), while in those Scott films the author can’t bring himself to defend someone else usually takes the blame. In examining 2000’s HANNIBAL, for instance, LoBrutto attributes that film’s shortcomings to its executive producer—“This really was a director-for-hire job: Dino de Laurentiis was the boss and Ridley Scott the craftsman”—while on 2006’s failed rom-com A GOOD YEAR he calls out its star Russell Crowe, who is “not funny or very romantic.”

Of Scott’s personal life only the most perfunctory details are included. We learn he’s been married three times and sired just as many children, dealt with the death of two siblings, is a clean freak and spends a few hours each day (whether he happens to be directing a film or not) dealing with the varied businesses he runs. In LoBrutto’s defense, Scott has never seemed too interested in letting the public in on more than that, making a fully-rounded biographical portrait difficult if not impossible.