The director-novelist: it’s a somewhat rare combination, but it does exist. In Europe and Great Britain, filmmakers like Betrand Blier, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Neil Jordan, Catherine Breillat, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Fernando Arrabal, Alan Parker and Marc Behm have dabbled, to varying degrees, in novel writing, while in the US the late filmmaker Samuel Fuller published a steady stream of novels throughout his life, and Edward D. Wood, Jr. wrote, or contributed to the writing of, around 80 paperbacks for the smut book market.

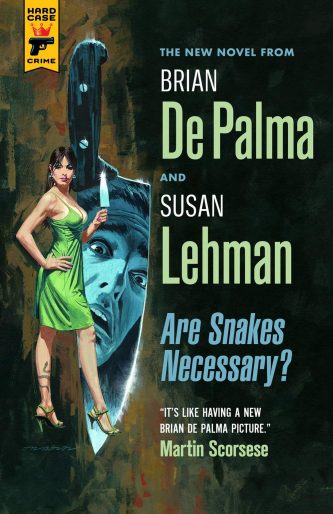

2020 was an especially fertile year for directors turned novelists, with the releases of the suspense thriller ARE SNAKES NECESSARY? by Brian De Palma (and Susan Lehman) and the unclassifiable ANTKIND by Charlie Kaufman, as well as THE LIVING DEAD by George Romero and Daniel Kraus, and THE NOTCH by Tom Holland. The latter two entries point to a most curious fact: that horror movie makers are by and large a more literary-friendly bunch than more respected mainstream directors.

2020 was an especially fertile year for directors turned novelists, with the releases of the suspense thriller ARE SNAKES NECESSARY? by Brian De Palma (and Susan Lehman) and the unclassifiable ANTKIND by Charlie Kaufman, as well as THE LIVING DEAD by George Romero and Daniel Kraus, and THE NOTCH by Tom Holland. The latter two entries point to a most curious fact: that horror movie makers are by and large a more literary-friendly bunch than more respected mainstream directors.

Why? Maybe because funding for horror cinema has become increasingly difficult to come by, resulting in filmmakers putting out their “films” in textual form (which, as we’ll see, was indeed the case in several of the following instances). Another, more likely possibility for the prevalence of genre affiliated filmmaker-novelists is that horror fans, contrary to what much of the world seems to believe, actually read a great deal.

The advantage for an established filmmaker turning to prose is evident in the fact that David Cronenberg, upon announcing he’d begun writing a novel in the early 2010s, was reportedly deluged with interested offers by publishers, and that Oliver Stone’s first and thus far only novel A CHILD’S NIGHT DREAM (1997) actually became a bestseller, even though many readers (this one included) judged it unreadable. The disadvantages should be obvious, as I think it goes without saying that far more people see movies than read books (note that none of Samuel Fuller’s novels have attained a fraction of the popularity of his films, and the same holds true for Mr. Wood), and that filmmaking talent doesn’t automatically translate to literary brilliance.

For proof of the latter assertion see LITTLE ORPHAN VAMPIRES (1995), the sole English language publication by the late French provocateur Jean Rollin. An 82-page trifle about vampire siblings on a sex and mutilation spree in Paris, it’s an uninspiring account that lacks the poetic charge and dark eroticism of Rollin’s best films. The fault may be with the translation by Peter Tombs, but the book feels rushed and perfunctory, more like an extended screen treatment than a proper novel. See also THE DOGFIGHTER, the sole novel by Jonathan Betuel, who scripted THE LAST STARFIGHTER (1984) and wrote and  directed MY SCIENCE PROJECT (1985). THE DOGFIGHTER was written nearly a decade prior to his work in Hollywood, yet Betuel’s screenwriter instincts are evident in the novel’s most glaring flaw: its dialogue-heavy treatment, which seems rather odd and out-of-place in a novel peopled by sub-literate rednecks.

directed MY SCIENCE PROJECT (1985). THE DOGFIGHTER was written nearly a decade prior to his work in Hollywood, yet Betuel’s screenwriter instincts are evident in the novel’s most glaring flaw: its dialogue-heavy treatment, which seems rather odd and out-of-place in a novel peopled by sub-literate rednecks.

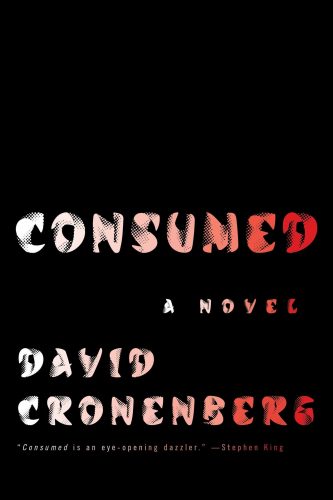

But of course the news here isn’t all bad. Regarding David Cronenberg’s attempt at novel writing, 2015’s CONSUMED, it’s not perfect, but did evince a unique and distinctive fictional voice. About a pair of workaholic journalists who share twin passions for technology and depravity, the novel encompasses venereal disease, dismemberment, cannibalism, insect eating and other arcane subject matter, making for a book that, unlike Cronenberg’s films, is quite expansive and overstuffed. It’s interesting enough, though, to suggest that Cronenberg could have a promising future in prose fiction.

The same was true for the late Wes Craven, who with FOUNTAIN SOCIETY turned out a strong piece of popular fiction. The novel appeared in 1999, when Craven, of LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT and A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET infamy, was looking to broaden his range (note the author description in the hardcover edition, which goes out of its way to tout “his first nongenre film, starring Meryl Streep and Aidan Quinn, a moving drama about a violin teacher in Spanish Harlem”). That explains the genre-hopping nature of the book, which encompasses horror, science fiction, espionage and romance in its tale of a brilliant scientist given new life, literally, in the body of a much younger man, courtesy of a top secret government-sponsored project. Drafted in a highly extroverted manner that doesn’t utilize too many big words, and featuring sexy and attractive protagonists, it’s very much in the mode of Dean Koontz, in whose bestselling footsteps Craven could well have followed.

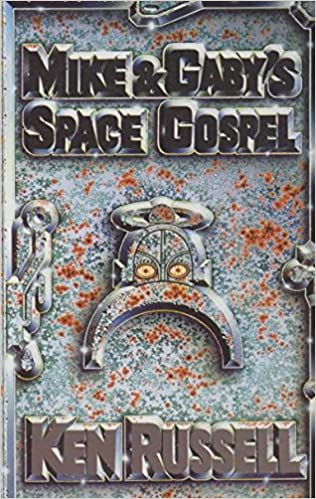

FOUNTAIN SOCIETY debuted around the same time as MIKE AND GABY’S SPACE GOSPEL, written by another genre-happy filmmaker making his  fictional debut: Ken Russell. The novel is a comedic science fiction reverie that retells the New Testament in the form of a “Space Gospel” in which a pair of all-powerful robots create a race of beings—humans—that bear a fundamental design flaw, for which a corrective is conjured in the form of a personage named Jesus Christ. The novel’s basis was a screenplay written by Russell and Derek Jarman that Russell was never able to film—hence MIKE AND GABY’S SPACE GOSPEL.

fictional debut: Ken Russell. The novel is a comedic science fiction reverie that retells the New Testament in the form of a “Space Gospel” in which a pair of all-powerful robots create a race of beings—humans—that bear a fundamental design flaw, for which a corrective is conjured in the form of a personage named Jesus Christ. The novel’s basis was a screenplay written by Russell and Derek Jarman that Russell was never able to film—hence MIKE AND GABY’S SPACE GOSPEL.

A subsequent Russell novel, 2005’s self-published VIOLATION, takes the themes of the former book ever farther. Its setting is a future world where a fellow named Jeez performs miracles amid a horrific landscape of torture, cannibalism, shape-shifting and giant bugs. Russell doesn’t exactly tame his wild side, which probably explains why VIOLATION was shunned by mainstream publishers—well, that and the fact that it’s sloppily written. That Ken Russell was not a novelist by trade is clear in the half-baked descriptions and wobbly narrative herein.

MIDNIGHT MOVIE was the only novel by THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE’S late Tobe Hooper (written in collaboration with Alan Goldsher). His hard-bitten, quintessentially Texan worldview is never less than thoroughly readable and inviting, utilized in service of a faux-documentary overlay of missives and interviews. It involves the screening of a lost, and apparently cursed, Hooper film at a shithole Texas venue, with the man himself on hand to introduce the screening. As a filmmaker Tobe Hooper was never known for his storytelling prowess, so I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that this novel is a bit light on narrative clarity. In ghoulish invention and black humor, however, it excels, and the film geek milieu it describes feels accurate (this, keep in mind, is from one who knows that milieu quite well).

THE NOTCH by Tom Holland is an odd book. Sprawling yet quite intimate in its scope, it relates what occurs over the course of two fateful days, during which an apparently autistic boy is discovered in a notch between two Arizona desert buttes. The boy, it quickly transpires, is able to heal wounds with the touch of a hand, which sets off a wave of madness that sees the boy come into contact with a band of gangbangers just as a deadly worldwide pandemic sweeps the land (rendering this a most appropriate 2020 release). At 478 pages the book is too long, but Holland, the writer- director of movies like FRIGHT NIGHT and CHILD’S PLAY, amply demonstrates his skill for plotting and structure in short 2-4 page chapters, with prose that positively surges with forward momentum. THE NOTCH is, in short, a page-turner.

director of movies like FRIGHT NIGHT and CHILD’S PLAY, amply demonstrates his skill for plotting and structure in short 2-4 page chapters, with prose that positively surges with forward momentum. THE NOTCH is, in short, a page-turner.

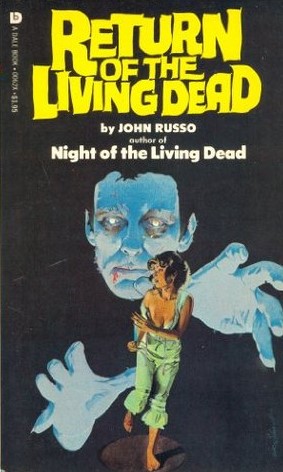

John Russo seems destined to remain best known for co-scripting George Romero’s NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968). Russo officially became a writer-director with the 1976 feature THE LIBERATION OF CHERRY JANOWSKI, a.k.a. THE BOOBY HATCH, after having novelized NIGHT two years earlier. A prose sequel, RETURN OF THE LIVING DEAD, followed in 1977; it was this novel that inspired the 1985 RETURN OF THE LIVING DEAD, although by the time that film went into production everything about Russo’s original had been completely changed—which didn’t stop Russo from writing the film’s novelization (around the same time as, to add further confusion, Romero’s own NIGHT sequel DAY OF THE DEAD was theatrically released).

The original RETURN novel is just okay, with Russo’s inexperience as a novelist all-too evident in the flat reportorial prose and overstuffed descriptions. Russo at least knows how to tell a good story, which has zombies terrorizing a portion of the United States Midwest, where a crashed bus disgorges a fresh batch of deaders. But of course it’s living, breathing humans that pose the greatest threat, as when several folk find themselves sequestered in a tiny house surrounded by zombies (again) and are attacked from within by a pair of miscreants looking to loot and pillage.

Russo’s next novel was THE MAJORETTES (1979), which like RETURN began life as a screenplay but ended up a novel (although that script was eventually filmed, unfortunately enough, in 1987). It’s better written than the previous book, but suffers from a by-the-numbers narrative involving a nut who kills majorettes and their lovers in a succession of gory passages that are neither shocking nor particularly inspiring. It took until 1983, with the impressive vampire epic THE AWAKENING, for Russo to reach his full potential as a novelist. As a filmmaker, alas, he has yet to fully blossom.

George Romero, Russo’s late NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD partner, appears to have had the opposite problem. His filmmaking legacy is secure, but  he never found his footing in the fictional realm, despite having had literary aspirations. Romero’s shortcomings as a prose stylist were proven by THE LIVING DEAD, a near 700 page zombie epic put together by Daniel Kraus. I feel it might have made more sense for Kraus’s name to appear first, as he was apparently the driving force behind this novel, finishing an incomplete manuscript by Romero and incorporating a short story, along with another novel-in-progress entitled THE DEATH OF DEATH.

he never found his footing in the fictional realm, despite having had literary aspirations. Romero’s shortcomings as a prose stylist were proven by THE LIVING DEAD, a near 700 page zombie epic put together by Daniel Kraus. I feel it might have made more sense for Kraus’s name to appear first, as he was apparently the driving force behind this novel, finishing an incomplete manuscript by Romero and incorporating a short story, along with another novel-in-progress entitled THE DEATH OF DEATH.

With so many disparate sources mixed in, it’s no surprise that THE LIVING DEAD is a choppy and discordant reading experience. It suffers from an excess of principals alive, dead and undead, as well as lugubrious prose (“We want to whisk her away from that hothouse, address her injured flesh, show her our own. Perhaps by doing do so, we can still be saved”) and the fact that zombies are officially a done-to-death subject. Twenty years ago THE LIVING DEAD may indeed have been the genre landmark it so desperately wants to be, but right now it comes off as a well-intentioned but late-to-the-party addendum.

Regarding the prolific moviemaker Mick Garris, the news is far better. Best known for his Stephen King film and TV adaptations, Garris has proven himself more adept at writing fiction than he is at making movies. His premiere work of fiction was “A Life in the Cinema,” a dark and perverse Hollywood horror story that first appeared in 1988 (the same year as Garris’s feature directorial debut CRITTERS 2: THE MAIN COURSE). It was incorporated into the collection A LIFE IN THE CINEMA in 2000, and formed the inception of a novel, DEVELOPMENT HELL, in 2006. The latter was what is known as a fixup novel, with its first half consisting of three tenuously related stories, beginning with the aforementioned “Life in the Cinema” and continuing with “Starfucker” and “A Hollywood Ending,” which takes us up to and beyond the protagonist’s death. As with most all of Garris’s fiction, the book is lively and imaginative, although the major criticisms that have been lobbed at it—that it’s overly episodic and fragmented—are dead-on.

Also worthy of mention here is Garris’s 2016 novella UGLY, a warped variant on VERTIGO and FRANKENSTEIN set, once again, in a debauched Hollywood milieu. In both novels Garris pointedly ignores his Hollyweird instincts, which decree that happy endings are a necessity and that the protagonist must be likeable. The endings of DEVELOPMENT HELL and UGLY are not what I’d call happy, and the first person protagonists of both  are irretrievable scumbags. Garris himself, I should add, is widely known for living up to the name of his company Nice Guy Productions, but we mustn’t forget Albert Camus’s claim that “fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth” about ourselves.

are irretrievable scumbags. Garris himself, I should add, is widely known for living up to the name of his company Nice Guy Productions, but we mustn’t forget Albert Camus’s claim that “fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth” about ourselves.

Further examples of genre filmmakers thriving in the fictional realm? Try Eric Red, the screenwriter of classic films like THE HITCHER and NEAR DARK, and director of the less-than-classic COHEN AND TATE and BODY PARTS. In 2012 he published DON’T STAND SO CLOSE, a terrifically perverse and suspenseful novel that suffers from some noticeable first-time writing mistakes and the type of plausibility issues that tend to plague Red’s scripts (such as an antagonist who in the climactic pages appears to have the ability to be in several different locations at once), but is quite powerful overall. About a teenage boy seduced by an attractive teacher, it’s well paced and furiously readable, with characterizations that ring consistently true. It was followed by several more Red penned novels, not all of them horror-themed.

The New York bred Buddy Giovinazzo is another filmmaker who found success (artistic, that is) writing fiction. Giovinazzo, whose horror accreditation is based primarily on his 1984 film COMBAT SHOCK, once told an interviewer that “When I want to get something out of my system—to get my rocks off—I write prose.” That prose was initially displayed in the 1993 collection LIFE IS HOT IN CRACKTOWN (which Giovinazzo adapted for film in 2009) and the 1996 novel POETRY AND PURGATORY.

Both showcase Giovinazzo’s penchant for big city ugliness and despair (as did COMBAT SHOCK), with the former being the superior book by far. The vision of urban desperation showcased in LIFE IS HOT IN CRACKTOWN is worthy of the writing of Hubert Selby, Jr., while POETRY AND  PURGATORY, about a street punk with terminal brain cancer, contains a rather uneasy mixture of grit and hallucination. A third Giovinazzo novel, the Berlin set mob thriller POTSDAMER PLATZ, appeared in 2004; far more conventional than its predecessors, it had the distinction of being optioned for film by the late Tony Scott, who provided an enthusiastic back cover blurb.

PURGATORY, about a street punk with terminal brain cancer, contains a rather uneasy mixture of grit and hallucination. A third Giovinazzo novel, the Berlin set mob thriller POTSDAMER PLATZ, appeared in 2004; far more conventional than its predecessors, it had the distinction of being optioned for film by the late Tony Scott, who provided an enthusiastic back cover blurb.

That about covers the category of horror directors turned novelists, but what about horror novelists turning to filmmaking? It happens, unfortunately. Check out the filmographies of John Farris, Stephen King, S.P. Somtow and Jay Bonansinga, accomplished horror novelists all who gave us the less-than-accomplished films DEAR DEAD DELILAH, MAXIMUM OVERDRIVE, THE LAUGHING DEAD and STASH. On the other hand, the veteran novelist/screenwriter William Peter Blatty adapted his 1966 novel TWINKLE, TWINKLE, “KILLER” KANE into the strange and moving self-directed film THE NINTH CONFIGURATION, so perhaps there’s hope for the novelist-filmmaker—but then again, Blatty followed that film with the considerably less moving EXORCIST III, so maybe not.

See Also: THE TWILIGHT WORLD by Werner Herzog.