I’m very sorry to bid farewell to Sir Alan Parker, who passed on July 31. One of the most gifted, and shamefully underrated, directors of his generation, the staunchly British Parker (who ironically set the majority of his films in the US) was known for nervy and hard-hitting cinema, albeit with a quintessentially Anglo sense of refinement. Many of his films were political in nature, yet all possessed a watchability factor that set them apart from those of Parker’s British rabble-rouser fellows. Had Ken Loach or Alan Clarke had made crowd-pleasing Hollywood fare those films would very likely have played like Alan Parker’s.

I’m very sorry to bid farewell to Sir Alan Parker, who passed on July 31. One of the most gifted, and shamefully underrated, directors of his generation, the staunchly British Parker (who ironically set the majority of his films in the US) was known for nervy and hard-hitting cinema, albeit with a quintessentially Anglo sense of refinement. Many of his films were political in nature, yet all possessed a watchability factor that set them apart from those of Parker’s British rabble-rouser fellows. Had Ken Loach or Alan Clarke had made crowd-pleasing Hollywood fare those films would very likely have played like Alan Parker’s.

A standout factor of Parker’s filmography is its versatility. Parker once stated that before he died he was determined to make a film in every genre, and he very nearly achieved that goal; science fiction is one genre he missed, but nearly all the others are represented. This is probably why, as a Telegraph article stated, he was “loved by audiences more than critics.” Critics, under the spell of the auteur theory (which states that the director is the “author” of a film, with recurring themes and motifs to announce his or her presence), have had a difficult time categorizing Parker’s films, which they saw as a bad thing. I say the opposite.

Here’s my take on Alan Parker’s filmography. Not included are the TV films he directed (such as 1975’s THE EVACUEES and the following year’s NO HARD FEELINGS), the script he wrote but didn’t direct (1971’s MELODY) and the two novels he published (PUDDLES IN THE LANE and THE SUCKER’S KISS, the latter of which comes highly recommended). Rather, what follows are my thoughts on Parker’s fourteen feature films, grouped as I feel they should be.

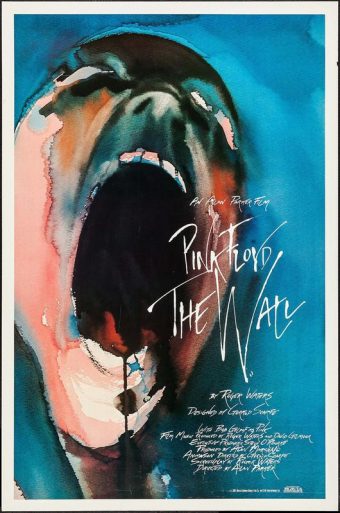

1. PINK FLOYD—THE WALL (1982)

The one and only film adaptation of Pink Floyd’s immortal rock opera THE WALL, about a drugged-out rock star who sequesters himself in a Los Angeles hotel suite and goes mad. Many people I know (even the so-called Pink Floyd fans) profess to despise this film, but I say it’s one of the most beautifully sustained visual assaults ever, with a great performance by Bob Geldof (yes, that Bob Geldof) and equally potent animation by Gerald Scarfe. Parker’s struggles with Roger Waters, who wrote the script, are legendary, and resulted in a film that reportedly turned out much darker and crazier than anyone anticipated (at its Cannes premiere one of the attendees, Steven Spielberg, is said to have turned to his seatmate, Universal CEO Sidney Sheinberg, during the end credits and asked “What the fuck was that?”). The mixture of animation and live action was and remains revolutionary, enhanced by a virtuosic cinematic technique that depicts the whorls of an unquiet mind in a manner that would have made the outré auteurs of the 1960s and 70s (Fellini, Russell, Jodorowsky, Bene, etc.) proud. This is, quite simply, the most brilliant, shocking, outrageous and all-around satisfying film ever made by Alan Parker, and that, as I feel the following films on this list adequately demonstrate, is no small claim.

2. THE COMMITMENTS (1991)

Very nearly the inverse of the above film, this is the high-spirited tale of a soul band formed by working class Irish youths that enjoys some (very) minor success before breaking up. The actors, most of whom never appeared in a movie before this one, all have an appealing naturalness, and prove quite adept as musicians (no joke: the soundtrack album was a hot seller in its day). Another of the film’s strengths is the all-pervading atmosphere of urban grit conjured by Parker, who translates the dialogue driven aesthetic of Roddy Doyle’s 1987 source novel into an unforgettably vivid cinemascape. The proceedings have an appealingly laid-back sensibility that nicely offsets all the ugliness, and while not a whole actually happens this is still an impossible-to-resist film.

3. MIDNIGHT EXPRESS (1978)

3. MIDNIGHT EXPRESS (1978)

This prison escape saga, adapted from the nonfiction account by Billy Hayes, is exploitive, xenophobic and outrageous—and also brilliantly pulled off in every respect. Parker’s first major success, it was scripted by Oliver Stone, who added many over-the-top elements to Hayes’ straightforward account of being interred in a Turkish prison during the early 1970s for drug smuggling, and his eventual escape. Parker proves himself a good match for the famously outspoken Stone, evincing a similarly bombastic bent. Also on display is an impressive grasp of the mechanics of thriller moviemaking, with the opening ten minutes, utilizing the oft-imitated (but never bettered) device of a beating heart on the soundtrack, being a masterclass in suspense. The film’s true spark, however, comes from the lead turn by the late Brad Davis, who has a genuinely troubled, uneasy air; that, combined with his unfettered emoting (the scene where he goes mad and nearly beats to death a fellow prisoner is still a bit too authentic for comfort), propels the film like a steam engine, and makes for an extremely exciting ride.

4. SHOOT THE MOON (1981)

This isn’t the movie Pauline Kael (who raved about it unreservedly) thought it was, but it is damn good. In fact, I’d say it’s the best entry in the divorce movie craze of the early 1980s (which included KRAMER VS. KRAMER, ORDINARY PEOPLE, SMASH PALACE and MY FIRST WIFE), a keenly observed drama about the break-up of an affluent Northern California couple, and the effect it has on their four children. The bizarrely (but potently) cast Albert Finney is at his best as George, an English writer with a hair-trigger temper, and Diane Keaton excels as his dissatisfied better half. Parker’s direction is (mostly) pitch perfect in creating an ambiance (there’s very little music of any sort) of unspoken pain and bitterness that boils over in several laceratingly violent scenes. Beautifully photographed from start to finish, it’s a definite standout in the oeuvre of Parker’s frequent cinematographer Michael Seresin. The ending, alas, ties everything up far too neatly (especially given that the rest of the film is so messy and complicated), and is a definite point of contention in an otherwise impeccable tapestry.

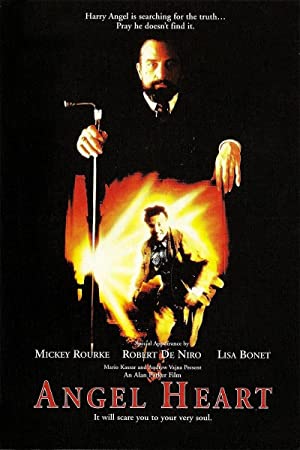

5. ANGEL HEART (1987)

Recalling Parker’s vow to work in every genre, ANGEL HEART was his nod in the direction of horror, combined with film noir. Based on William Hjortsberg’s excellent 1978 novel FALLING ANGEL, it’s the Raymond Chandler-meets-Stephen King story of Harry Angel (Mickey Rourke), a hardboiled private dick tracking down a mysterious singer on the orders of a weird dude named Lou Cypher (Robert De Niro). The film starts out in late-fifties NYC and then, unlike the book, takes a detour into New Orleans. I think this was a mistake, as the book’s big city setting made for a memorably bizarre contrast to the black magic that accompanies Angel on his search. The film also feels a bit overly drawn-out, sorely lacking the book’s headlong drive. On the plus side, Rourke is quite effective in the title role, as is THE COSBY SHOW’S Lisa Bonet as the requisite femme fatale, and Parker and Seresin do their usual fine job creating a dark, forbidding visual landscape.

6. THE ROAD TO WELLVILLE (1994)

With this adaptation of T. Coraghessan Boyle’s period novel about John Harvey Kellogg (the cereal guy) and his Battle Creek Wellness sanitarium, Parker delivered a film that’s weird, off-putting and lewdly funny. It’s also a bit dull and formless overall, but has enough diverting raunchiness to be classified as a conditional success—think of it as an early twentieth century PORKY’S. Anthony Hopkins is hilarious as the buck toothed Kellogg, and Matthew Broderick, John Cusack, Bridget Fonda and a scene-stealing Lara Flynn Boyle offer terrific support. As for Dana Carvey as Kellogg’s wayward son, he doesn’t have nearly enough to do, with the kid who plays him in flashbacks (GUMMO’s Jacob Reynolds) making a far greater impression.

7. BIRDY (1984)

7. BIRDY (1984)

Here Parker adapted William Wharton’s bizarre 1978 novel BIRDY, about a pair of traumatized ‘Nam vets, one of whom (Nicolas Cage) is suffering from a severe facial wound while the other (Matthew Modine) has gone mad, believing he’s a bird. Flashbacks fill us in on these guys’ early years in a Philadelphia suburb, and the unlikely but enduring friendship they forge. It’s in those flashbacks, alas, that Parker made his first big mistake, by having Cage and Modine play themselves even though both were far too old to be convincing as preteens. Parker’s second mistake was hiring Peter Gabriel to do the music; to be sure, Gabriel has done some great film scoring in the years since (on THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST and RABBIT-PROOF FENCE), but here, in his first such attempt, he delivers a consistently distracting electronic score that feels wholly out of place. Yet BIRDY is (once again) beautifully visualized by Mr. Seresin, and consistently absorbing no matter how strange it gets, with a final scene that can be viewed as a brilliant bit of semi-comedic incongruity or a profound misconception; truthfully I’m not sure on which side I fall.

8. COME SEE THE PARADISE (1990)

This romantic drama wasn’t much of a success critically or financially, but I say it deserved better than it got. Set during WWII, it’s about the millions of Japanese Americans who were shipped off to concentration camps during the years 1942-45. Yes, the interracial love story at its center, between Dennis Quaid as a white soldier and Tamlyn Tomita as a Japanese-American woman who’s exiled to a detention camp together with her family, is rather superfluous (having been inserted, evidently, to entice white viewers), but the film overall is more entertaining than it has any right to be, and (of course) looks great. At the very least, COME SEE THE PARADISE deserves credit for being the only feature film ever made about this troubling but vital chapter in America’s history.

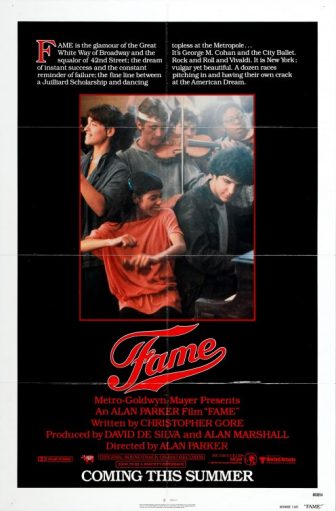

9. FAME (1980)

Touted as a high energy musical, FAME is actually a tough-minded and rather depressing account of the pratfalls of fame, as seen through the (mis)fortunes of several eager kids making their way through New York’s High School for the Performing Arts. One such kid who leaves for Hollywood early on in the film is stuck waiting tables by its end, while another thinks she’s landed a big movie roll only to end up sexually harassed by a camcorder wielding slob. Parker brings all his expected visual brilliance and dramatic fatalism to the proceedings, and a good thing, because the characters by and large aren’t very interesting.

10. ANGELA’S ASHES (1999)

Better than I expected, but still no masterpiece, this film was adapted from the famed 1996 book by Frank McCourt, an autobiographical account of his impoverished prewar childhood in Limerick, Ireland. Unsurprisingly, this film is said to be a lot darker than the book, although it seems to me that Parker had mellowed quite a bit here, in what was to be his second-to-last feature. ANGELA’S ASHES features an excellent performance by the ever-dependable Emily Watson (as the protagonist’s mother) and remains highly diverting throughout its expansive 2½-hour running time. The problem is the whole thing is just too damned “respectable” and (in the category of prestige biopics) by-the-numbers. A chief virtue of Parker’s best films, let’s not forget, was their wily unpredictability, and despite quite a few squalid and disturbing aspects there aren’t any real surprises to be found in ANGELA’S ASHES.

11. MISSISSIPPI BURNING (1988)

11. MISSISSIPPI BURNING (1988)

This film was highly controversial back in the day for its heavily fictionalized depiction of the murders of three civil rights activists in 1960s Mississippi. Specifically, Parker made his protagonists a pair of white FBI agents, one a by-the-book whipper snapper (Willem Dafoe) and the other an ass-kicking veteran (Gene Hackman), a clichéd pairing that’s not dissimilar to those of the innumerable cop thrillers being made at the time. As always, Parker and his collaborators do superlative work, with period detail that’s impeccable, but the film’s detractors have a point. The film’s downtrodden African American victims are presented, quite obnoxiously, as childlike waifs who need to be protected (by white people, of course), and the brutality-heavy narrative lacks momentum. Parker’s script, with its retinue of beatings, shootings, hangings, etc., appears to have been attempting to recapture the shock and awe of MIDNIGHT EXPRESS. Quite simply: it doesn’t work.

12. EVITA (1996)

An adaptation of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical extravaganza about the life of Eva Peron, the “greatest social climber since Cinderella.” Parker brought this material to the screen with Webber’s songs and music intact, resulting in an impressive technical achievement but a rather distant and uninvolving viewing experience; or, as Leonard Maltin called it, the “longest music video ever.” Madonna is admittedly quite strong in the lead role (although her casting would be branded politically incorrect nowadays), and Jonathan Pryce as her hubbie provides excellent support. But the overly burnished cinematography is a perpetual annoyance, as are the near-constant crowd scenes, which feel gratuitous and show-offy. See Andrzej Zulawski’s masterful musical epic BORIS GOUDONOV (1989) and, for that matter, PINK FLOYD—THE WALL for what EVITA should have been.

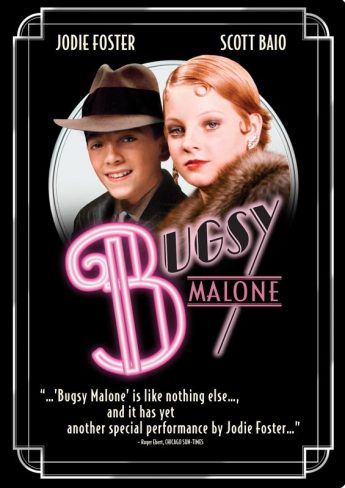

13. BUGSY MALONE (1976)

Parker’s debut film was this goofy musical that knowingly apes the American gangster movie classics, with a cast comprised entirely of children (led by Scott Baio and Jodie Foster) equipped with cream pie shooting guns. What’s interesting is that Parker takes this ridiculous conceit entirely seriously, avoiding overt comedy, and the songs by Paul Williams (coming off PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE) are toe-tappers for the most part. Otherwise, though, this film is utterly inconsequential fluff that vastly over-relies on cuteness. That’s a mistake, thankfully, that Parker never made again.

14. THE LIFE OF DAVID GALE (2003)

This near-inexcusably awful thriller was, sadly, the last film to be directed by Mr. Parker. I understand he attempted to mount some subsequent film projects in the ensuing years (and published the aforementioned novel THE SUCKER’S KISS), but it seems he took a bit of advice he doled out in a 1990 American Film interview, that old people shouldn’t direct films because it’s “too fucking hard,” to heart. Perhaps that wasn’t such a bad thing, judging by the lackluster and misconceived LIFE OF DAVID GALE. It attempts to do for capital punishment what MISSISSIPPI BURNING did for racism in its story of an anti-death penalty activist (Kevin Spacey) convicted of murder, and the journalist (Kate Winslet) sent to interview him. There is, at least, some snarky enjoyment to be had from the sight of an overacting Kate Winslet gasping and crying in front of a TV monitor (which she does on at least three separate occasions) and the utterly ludicrous final twist, which has the effect of rendering a ridiculous story even more so.