On March 16, 2002, the Italian writer/actor/filmmaker Carmelo Bene passed away. A true iconoclast, the eccentric and gifted Bene was the foremost guitto (barnstormer) of the Italian stage, a title he effectively parlayed into the realms of literature and cinema. Bene’s art, which includes countless plays, several novels and five extraordinary films, is near completely unknown in North America. Perhaps it was Bene’s total absorption in all things Italian, from beatific Roman scenery to sentimental arias (which provided the music for his films), or his love of excess and grotesquerie that has thus far kept his work from these shores. Whatever the reason, let’s hope our access to the art of this criminally neglected genius becomes more readily available in the coming years, as it’s among the most vital of the past century.

I’ll refrain from discussing Bene’s novels and plays in favor of his cinematic endeavors, which more than stand on their own. NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI (1968), CAPRICCI (’69), DON GIOVANNI (’70), SALOME (’72) and UN AMLETO DI MENO (’73) remain vital and unprecedented viewing experiences nearly thirty years after their collective inception, with at least two bonafide masterworks among them.

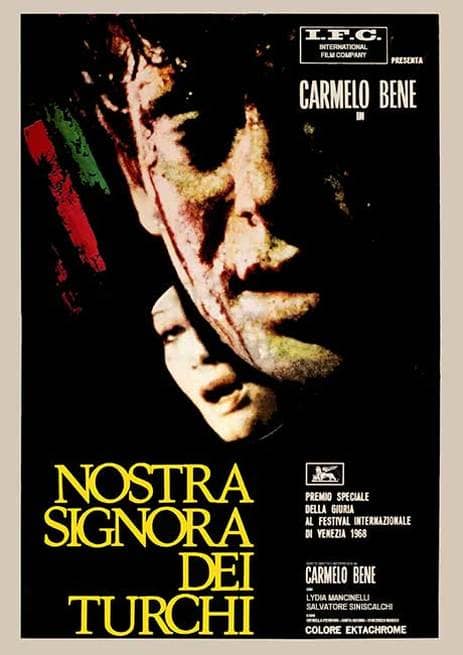

Bene’s debut film NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI (OUR LADY OF THE TURKS) is one of his signature achievements. The subject was ostensibly the 1480 invasion of Bene’s childhood home Otranto, when the Turkish fleet massacred 800 of the inhabitants, but I admittedly had difficulty discerning any such conception. There’s nothing resembling a narrative, linear or otherwise, with only Bene’s eye-popping pictorial sense—one as stunning as that of any filmmaker since D.W. Griffith—binding together this phantasmagoric swirl of light and sound.

Bene’s debut film NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI (OUR LADY OF THE TURKS) is one of his signature achievements. The subject was ostensibly the 1480 invasion of Bene’s childhood home Otranto, when the Turkish fleet massacred 800 of the inhabitants, but I admittedly had difficulty discerning any such conception. There’s nothing resembling a narrative, linear or otherwise, with only Bene’s eye-popping pictorial sense—one as stunning as that of any filmmaker since D.W. Griffith—binding together this phantasmagoric swirl of light and sound.

NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI’s protagonist is played in ultra-histrionic fashion by Bene himself, a veritable human cartoon with his rugged yet comically bug-eyed appearance (his face always seems contorted into a caricature of ecstatic joy or extreme agitation). He scales the walls of a crumbling church to stand, strikingly, with his face silhouetted against a blinding sun. Jungle vegetation invades the interior of a house, which is further violated by a car that parks beside a bed. Bene injects his naked buttocks in a crowded square and later tries to make love, seemingly unaware that he’s wearing a clunky suit of armor. And so on. In Bene’s visual sphere a jeweled broach in close up is as visually compelling as the sight of gunmen stalking through tall grass; a slow pan around an ancient building as haunting as the visage of a mysterious, angelic woman that appears in a hand mirror to blend eerily with the purveyor’s own face.

NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI never coalesces into any sort of coherent whole; all connections are of the subconscious variety, bolstered by transitions of swirling, bleeding color. Critics of the time assigned much political significance to this breathtaking work (excepting the Sight and Sound scribe who wrote that it “makes no sense whatsoever”), though nowadays the film is probably best viewed as a demented travelogue through an Italy of dreams. Or nightmares.

If Bene could be said to have a cinematic predecessor it would be the Bunuel of L’AGE D’OR (1930) or possibly fellow countrymen like Fellini and Pasolini (for whom Bene played Creon in EDIPO RE, 1967). In point of fact, Bene’s most conspicuous forbears are theatrical (Artaud’s theater of cruelty was an acknowledged influence) and literary. NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI is ultimately reminiscent of nothing so much as Conte De Lautreamont’s pre-surrealist masterpiece LES CHANTS DE MALDOROR (THE CHANTS OF MALDOROR), which it matches in transgression and sheer beauty. Consider the following MALDOROR excerpt, which captures the essence of Bene’s cinematic universe far better than any mere description: “I have taken a pocket-knife and severed the flesh at the spot where the lips come together…I looked into the mirror and inspected the mouth I had deliberately butchered. It was a mistake! The blood falling copiously from the wounds made it impossible to distinguish whether this was really the laughter of other men…”

If Bene could be said to have a cinematic predecessor it would be the Bunuel of L’AGE D’OR (1930) or possibly fellow countrymen like Fellini and Pasolini (for whom Bene played Creon in EDIPO RE, 1967). In point of fact, Bene’s most conspicuous forbears are theatrical (Artaud’s theater of cruelty was an acknowledged influence) and literary. NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI is ultimately reminiscent of nothing so much as Conte De Lautreamont’s pre-surrealist masterpiece LES CHANTS DE MALDOROR (THE CHANTS OF MALDOROR), which it matches in transgression and sheer beauty. Consider the following MALDOROR excerpt, which captures the essence of Bene’s cinematic universe far better than any mere description: “I have taken a pocket-knife and severed the flesh at the spot where the lips come together…I looked into the mirror and inspected the mouth I had deliberately butchered. It was a mistake! The blood falling copiously from the wounds made it impossible to distinguish whether this was really the laughter of other men…”

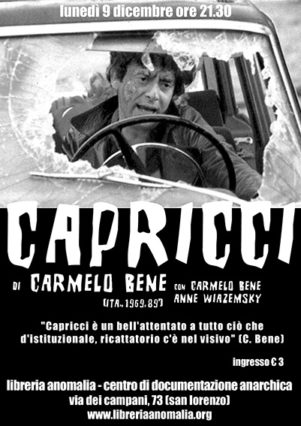

Bene named Francis Bacon and James Joyce as further progenitors, but claimed his cinematic preferences ended with Keaton and Eisenstein. He  did, however, once confess to liking Godard’s PIERROT LE FOU, a film whose influence is apparent in Bene’s heavily self-referential second feature CAPRICCI. It’s another melange of frenzied imagery, though with a singularly mordant sense of humor best displayed in an early scene depicting two men engaged in a violent duel, one armed with a hammer and the other a sickle! There’s also a sputtering old man trying—and failing—to have sex with a nubile seductress (seemingly a variation on the suit of armor gag from the earlier film) and an endless series of car crashes (shades of another late-60’s Godard film).

did, however, once confess to liking Godard’s PIERROT LE FOU, a film whose influence is apparent in Bene’s heavily self-referential second feature CAPRICCI. It’s another melange of frenzied imagery, though with a singularly mordant sense of humor best displayed in an early scene depicting two men engaged in a violent duel, one armed with a hammer and the other a sickle! There’s also a sputtering old man trying—and failing—to have sex with a nubile seductress (seemingly a variation on the suit of armor gag from the earlier film) and an endless series of car crashes (shades of another late-60’s Godard film).

He did once confess to liking Godard’s PIERROT LE FOU, a film whose influence is apparent in Bene’s heavily self-referential second feature CAPRICCI.

CAPRICCI is a superbly calibrated swirl of expressionistic filmmaking, but it hasn’t dated well. Lacking the creative exuberance of the previous film, it tends to fall back on sophomoric shock value, which has for the most part worn off; the copious auto wrecks and explosions, for instance, have long since been outdone by Hollywood. Furthermore, while governed by the same dream logic that characterized NOSTRA…, much of CAPRICCI simply feels disjointed. It seems Bene had nearly worn out his self-created aesthetic after just two films; clearly, a change in direction was needed.

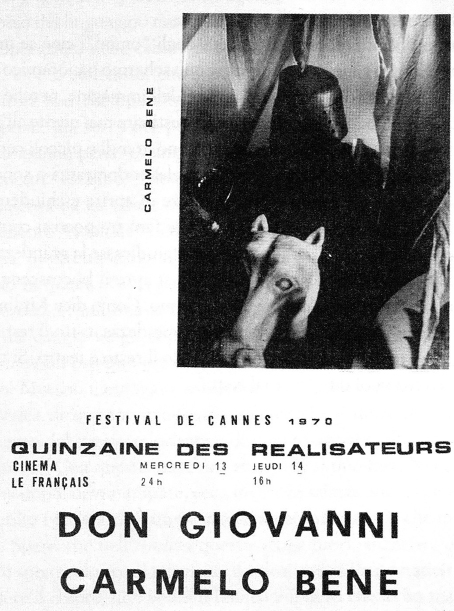

DON GIOVANNI, a baroque and claustrophobic take on the incest episode of Mozart’s opera, features Bene as the eponymous Don, who spends much of the 72-minute running time crawling through a twisted heap of barbed wire. It follows the non-linear contours set by the earlier films, but new elements are introduced: a deliberately artificial stage-bound setting and a simultaneously eye-pleasing and off-putting color scheme utilizing splashes of red amidst near-bilious shades of orange.

DON GIOVANNI, a baroque and claustrophobic take on the incest episode of Mozart’s opera, features Bene as the eponymous Don, who spends much of the 72-minute running time crawling through a twisted heap of barbed wire. It follows the non-linear contours set by the earlier films, but new elements are introduced: a deliberately artificial stage-bound setting and a simultaneously eye-pleasing and off-putting color scheme utilizing splashes of red amidst near-bilious shades of orange.

…a baroque and claustrophobic take on the incest episode of Mozart’s opera, features Bene as the eponymous Don…

DON GIOVANNI is ultimately most significant as the jumping-off point for its creator’s drift away from the real-life settings and concerns of his previous films toward a hermetic arena of pure expressionism, a tendency that reached its apex in Bene’s next and most astonishing film.

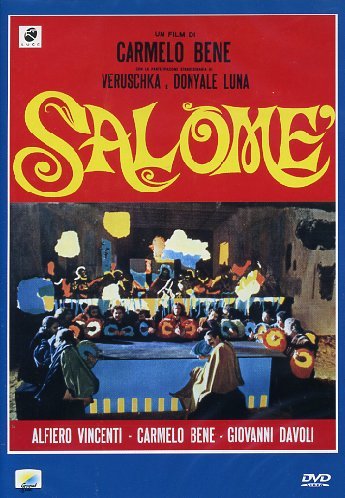

SALOME owes less to Oscar Wilde than to Bene’s life-long infatuation with Italian pop art in all its gaudy excessiveness. All traces of “reality” have been banished from this near-indescribable romp through Carmelo Bene’s cinematic universe that fully embodies Alberto Moravia’s oft-quoted impression of Bene’s work: “Desecration by dissociation, pushed beyond the point of schizophrenic delirium.”

Highlighted by exuberantly tacky set design, eye-burning colors, ever-changing illumination (the lighting has a tendency to unexpectedly blink, dim and brighten) and a soundtrack that rarely ever plays by the rules (it’s a scant occasion when the images match the sound, which oft-times cuts out altogether), disorientation is the norm with SALOME. Indeed, part of the film’s fascination is in attempting to decipher just what is happening at any given time, a quandary enhanced by wildly insistent rapid-fire editing. Think of it as a Michael Bay remake of FELLINI SATYRICON (a film Bene references by featuring one of its main cast members, the exotically alluring Donyale Luna, in the title role), or, with its two-dimensional florescent props, an Andy Warhol-designed episode of PEE WEE’S PLAYHOUSE.

Highlighted by exuberantly tacky set design, eye-burning colors, ever-changing illumination (the lighting has a tendency to unexpectedly blink, dim and brighten) and a soundtrack that rarely ever plays by the rules (it’s a scant occasion when the images match the sound, which oft-times cuts out altogether), disorientation is the norm with SALOME. Indeed, part of the film’s fascination is in attempting to decipher just what is happening at any given time, a quandary enhanced by wildly insistent rapid-fire editing. Think of it as a Michael Bay remake of FELLINI SATYRICON (a film Bene references by featuring one of its main cast members, the exotically alluring Donyale Luna, in the title role), or, with its two-dimensional florescent props, an Andy Warhol-designed episode of PEE WEE’S PLAYHOUSE.

…exuberantly tacky set design, eye-burning colors, ever-changing illumination (the lighting has a tendency to unexpectedly blink, dim and brighten) and a soundtrack that rarely ever plays by the rules…

That’s not to say Carmelo Bene’s SALOME resembles anything else, and that includes the countless film adaptations of Wilde’s text. This is certainly the only version featuring a man nailing himself to a flashing neon cross…or wherein the eponymous vixen literally peels the skin from the face of Kind Herod (played by Bene) as an act of seduction, precipitating his—and the film’s—final descent into utter madness, with the camera zooming madly in and out in an apparent admission of its failure to adequately capture such insanity. As for the all-important Dance of the Seven Veils, the pinnacle of outrageousness in most productions, the sequence here is, ironically enough, the most quietly lyrical of the entire film.

As for the all-important Dance of the Seven Veils, the pinnacle of outrageousness in most productions, the sequence here is, ironically enough, the most quietly lyrical of the entire film.

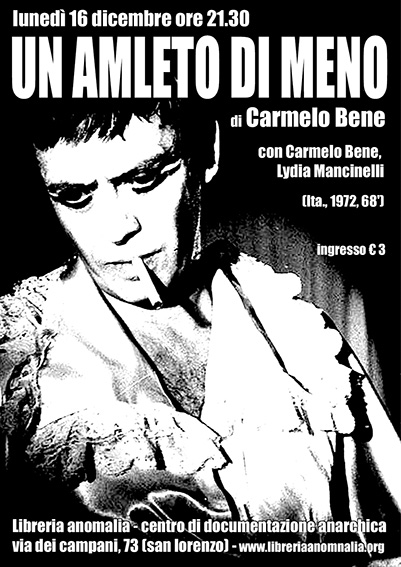

With SALOME behind him, Bene’s interest in cinema declined; he made just one more film, UN AMLETO DI MENO (ONE HAMLET LESS), an adaptation of one of his best-known stage works. A hallucinatory take on HAMLET inspired in equal parts by Shakespeare and the French surrealist poet Jules Laforgue, UN AMLETO DI MENO utilizes outrageously opulent costumes and a color scheme composed primarily of shades of blue. The action is only slightly less frenzied than that of SALOME, with naked women in nun’s habits cavorting amidst all white backgrounds, giant red balls, a cemetery on a beach and a fabulous glass coffin. It seems curiously appropriate that in the midst of such unrestrained lunacy, when the king is crowned in the end he (quite literally) has no face.

With SALOME behind him, Bene’s interest in cinema declined; he made just one more film, UN AMLETO DI MENO (ONE HAMLET LESS), an adaptation of one of his best-known stage works. A hallucinatory take on HAMLET inspired in equal parts by Shakespeare and the French surrealist poet Jules Laforgue, UN AMLETO DI MENO utilizes outrageously opulent costumes and a color scheme composed primarily of shades of blue. The action is only slightly less frenzied than that of SALOME, with naked women in nun’s habits cavorting amidst all white backgrounds, giant red balls, a cemetery on a beach and a fabulous glass coffin. It seems curiously appropriate that in the midst of such unrestrained lunacy, when the king is crowned in the end he (quite literally) has no face.

A triumph for Bene’s usual cinematographer Mario Masini, the visually stunning UN AMLETO DI MENO is both a fitting summation of Bene’s filmic interests and a glimpse of a tantalizing new direction for this most idiosyncratic of filmmakers. Sadly, the hoped-for cinematic follow-up never materialized.

Plagued by lifelong health problems, Bene rounded out his remaining years with theatrical, literary and even some television projects. He also created a super-8 short pontificating on the superiority of Buster Keaton over Charlie Chaplin (whom Bene regarded as a “spokesman for bourgeois sentimentality”) and in 1994 made a memorable two-hour long, one-man appearance on Italy’s most popular late night talk show. His death was appalling for all the future projects denied us, but Bene accomplished more with a scant five features than most other filmmakers can ever hope to attain. Carmelo Bene’s is a filmography that merits a vastly overused but rarely warranted description: there is truly nothing else like it.