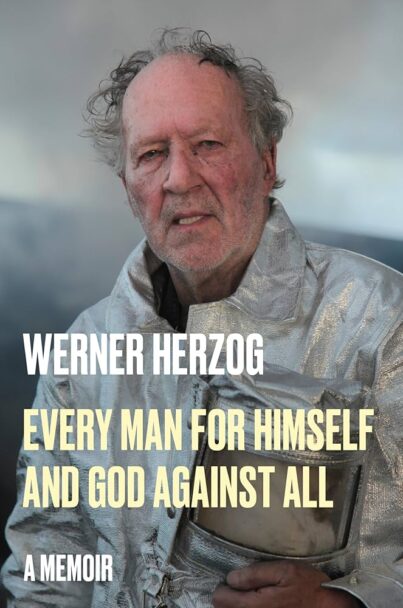

By WERNER HERZOG (Penguin Press; 2022/23)

By WERNER HERZOG (Penguin Press; 2022/23)

For fans of the German filmmaker and sometime actor Werner Herzog this long-in-coming memoir may seem a bit anti-climactic. This is to say that the colorful and gregarious Herzog, whose outsized media presence is unique among contemporary directors, has aired the details of his life quite voluminously over the years, meaning most of the stories related in this book have already been told. Yet Herzog’s voice, inflected with a quintessentially Germanic grandiosity and a highly quirky poetic dissonance, is always fascinating (I haven’t listened to the Herzog narrated audio version of this book, but it’s probably the best way to experience it).

In keeping with Herzog’s quirky orientation, EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF AND GOD AGAINST ALL has a structure that’s loose-to-nonexistent. Herzog makes an attempt at chronology in the first half, describing his childhood in Germany and teenage wanderings in the US in some detail, but can’t keep from frequently jumping forward whenever some later anecdote occurs to him.

Herzog writes about being born “before the turning point of the Second World War.” He’s quite frank about his parents’ Nazi affiliations (both underwent a “de-Nazification” process) and the “extreme poverty” in which he and his brother Till (who became a wealthy businessman) were raised. In his adolescence Herzog converted for a brief time to Catholicism, and then began making short films, with his debut feature being 1968’s SIGNS OF LIFE/Lebenszeichen. His approach to filmmaking was formed in large part by the fact that he hadn’t seen any films growing up, meaning “I would have to come up with a cinema of my own.”

Herzog claims no affinity with the New German Cinema in which he’s often included, and of its members says he’s only friendly with THE TIN DRUM’s Volker Schlondorff. Other noteworthy acquaintances include the Australian novelist Bruce Chatwin (whose novella THE VICEROY OF OUIDAH Herzog adapted for film as COBRA VERDE), the French tightrope walker Philippe Petit, the possibly insane actor Bruno S. (who headlined the 1974 film that provided this book’s title), the avant-garde film programmer Amos Vogel and Herzog’s “best fiend” and frequent casting choice Klaus Kinski.

Of Herzog’s films, AGUIRRE: THE WRATH OF GOD/Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes (1972) and FITZCARRALDO (1982) get the most coverage. AGUIRRE was shot in the Amazon jungles not far from where Juliane Koepcke, a seventeen year old Peruvian, found herself stranded after miraculously surviving the destruction of a plane that Herzog himself nearly boarded (Herzog, for the record, made a 1999 documentary about Koepcke’s ordeal). FITZCARRALDO, which involved a massive ship dragged over a mountain, was a profoundly arduous undertaking whose inception involved multiple injuries—again, though, that’s something most Herzog fanatics will already know.

Herzog makes sure to describe many of his own highly eccentric actions, including the public eating of one of his shoes (due to a bet he had with filmmaker Errol Morris) and his love of walking. He recounts numerous foot journeys, including an epic 1974 trek from Munich to Paris that was detailed in the book OF WALKING IN ICE (excerpts from which are included here), and another around the border of Germany, in order to “hold it together like a belt.” He also claims to have started a “Rogue Film School” whose sole lessons are “the forging of documents and the cracking of Yale locks.”

To fully cover Herzog’s varied life would require a book much longer than this one. Nor does this text outdo Paul Cronin’s WERNER HERZOG—A GUIDE FOR THE PERPLEXED (2014) as the definitive print resource on this endlessly fascinating figure. Nonetheless, readers wanting the skinny on all things Werner Herzog will come away from EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF AND GOD AGAINST ALL sated.