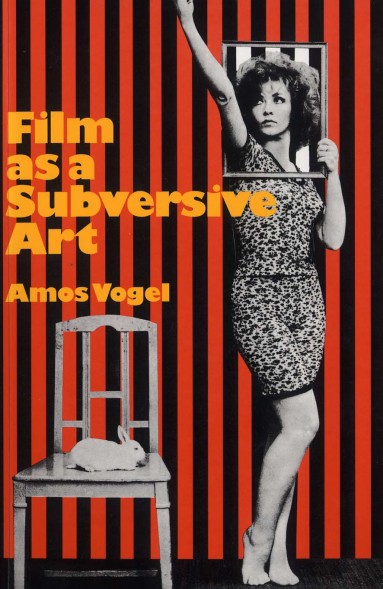

Norman Mailer once proclaimed FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART by Amos Vogel “the most exciting and comprehensive book I’ve seen on avant-garde, underground and exceptional commercial film.” Excellent point, but I’d take that praise farther: I believe FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART is the most exciting and comprehensive film book I’ve seen, period. Since my initial discovery back in the mid-nineties (more on that in a bit) of this shocking, provocative and altogether brilliant book, nary a year has passed during which I haven’t given it several perusals, each time finding something I hadn’t previously noticed.

Norman Mailer once proclaimed FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART by Amos Vogel “the most exciting and comprehensive book I’ve seen on avant-garde, underground and exceptional commercial film.” Excellent point, but I’d take that praise farther: I believe FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART is the most exciting and comprehensive film book I’ve seen, period. Since my initial discovery back in the mid-nineties (more on that in a bit) of this shocking, provocative and altogether brilliant book, nary a year has passed during which I haven’t given it several perusals, each time finding something I hadn’t previously noticed.

Some background: the Vienna-born Amos Vogel (1921-2012), a political radical and rabid film buff, immigrated to America in the late 1930s. Among his accomplishments was the founding of the New York based Cinema 16 (1947-63), a membership club patterned on the European film society model that sought “to further the appreciation of film and of new experiments in the medium.” Film 16’s orientation was in keeping with Vogel’s admitted taste for “crazy stuff,” and if anyone dared complain Vogel’s alleged response was “Oh, you don’t like it? We’ll show it again!” For many years Cinema 16 was the only venue where experimental and avant-garde films could be exhibited, and it remains fondly remembered by East Coast film nerds (being the subject of the 2003 documentary FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART: AMOS VOGEL AND CINEMA 16).

But Vogel’s most impacting endeavor in my view will always be FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART. Published by Random House in 1974, it was the culmination of Vogel’s endeavors with Cinema 16, and also as program director for the New York Film Festival from 1963-68, packing all his accumulated filmic knowledge and left-leaning political convictions into a full-to-overflowing 336 page tome.

It’s a book whose design and layout are as important as (if not more so than) the text. Juxtaposed are three distinct portions:  essays that begin each chapter, detailing the subject matter covered, followed by highly learned and politically informed film reviews, alongside copious black and white stills and explanatory paragraphs, many of which serve as mini-reviews in their own right.

essays that begin each chapter, detailing the subject matter covered, followed by highly learned and politically informed film reviews, alongside copious black and white stills and explanatory paragraphs, many of which serve as mini-reviews in their own right.

The films covered include underground mainstays like MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON (“a work that distorts and intermingles past and present, time and place, reality and fantasy until they are seen as a potential or real continuum”), FIREWORKS and THE ACT OF SEEING WITH ONE’S OWN EYES, as well as the more obscure likes of ORDINARY COURAGE (1964), VISUAL TRAINING (1969) and something called LE SANG (“An apocalyptic vision of man after a cosmic catastrophe, this film is a terrifying metaphor of a dehumanized future”). In short, all the “crazy stuff” Vogel liked to show at Cinema 16 is represented, contained by chapter headings like “Surrealism: The Cinema of Shock,” “International Left and Revolutionary Cinema,” “The End of Sexual Taboos: Erotic and Pornographic Cinema” and “The Terrible Poetry of Nazi Cinema” (that latter was among Vogel’s most controversial Cinema 16 offerings, so he made sure to include plenty of Nazi-themed film reviews here).

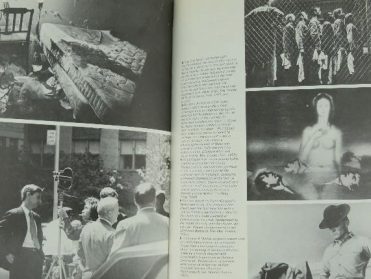

The stills, many of them unique to this book, serve not as mere illustrations but as compliments to and extensions of the text–and Vogel, you can be sure, has no problem juxtaposing the mundane with the taboo. A still from Bernardo Bertolucci’s BEFORE THE REVOLUTION (1964), showing a woman grasping a man’s hand, is included for its geometric composition (“Adriana Asti’s luminous eyes parallel the positioning of the hero’s arm and lead us toward him”), while a series of stills from the short film OTMAR BAUER PRESENTS (a.k.a. ZEIGT; 1969) depict a guy vomiting all over himself (“All bodily secretions…are considered taboo in terms of visual portrayal…we remain chained to notions of the body’s uncleanliness and animality”).

Other less-than-family friendly stills include a machine gun toting American soldier standing on a corpse in WINTER SOLDIER (1972), a fly landing on a woman’s nipple in Yoko Ono’s FLY (1970) and a mountain of corpses from NIGHT AND FOG (1955). Again: there are plenty of other, non-explicit stills, but I suspect the nasty and disturbing ones will be what most people notice (so for the squeamish among you, take that as a warning).

Other less-than-family friendly stills include a machine gun toting American soldier standing on a corpse in WINTER SOLDIER (1972), a fly landing on a woman’s nipple in Yoko Ono’s FLY (1970) and a mountain of corpses from NIGHT AND FOG (1955). Again: there are plenty of other, non-explicit stills, but I suspect the nasty and disturbing ones will be what most people notice (so for the squeamish among you, take that as a warning).

Despite a few notable omissions (Alejandro Jodorowsky’s EL TOPO, one of the most prominent avant-garde features of the early 1970s, is mentioned nowhere in the text), FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART can lay claim to being the premiere avant-garde film resource. Yet it also includes mainstream offerings like KING KONG (“Shall we ever accept—or overcome—the horror (however delicious) evoked in us by this curious monster?”) and DR. STRANGELOVE, which may well be the most “subversive” thing about it.

My feelings about this book will always be based upon my own history with it. I discovered FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART, fortuitously enough, during my formative years as a film student. Specifically, I was on my winter break when I stumbled upon a trade paperback copy at a So Cal Border’s, and was immediately enthralled. As one who was just discovering the joys of avant-garde cinema the book was a revelation, marking my first introduction to the iconoclastic cinema of filmmakers like Carmelo Bene and Fernando Arrabal, and films like THE CREMATOR and THE BLOODTHIRSTY FAIRY (both 1969). I made sure to bring the book with me when I returned to class, certain my fellow students would be as enchanted as I was. Thus I was quite surprised when they objected to it, in some cases quite violently; as one of my pals ranted, “it’s books like this that make me despise film!”

The trigger for his upset was not Vogel’s choice of subject matter or the stills, but rather the academic overlay. Given that  Vogel was a film professor at the University of Pennsylvania when this book was written, it makes sense that much of it is taken up with text like “There have always existed in the plastic arts tendencies towards forms and images undefiled by representations of reality.” Such highbrow preening can be deadly, especially to film students grinding out subtextual analyses of HIROSHIMA, MON AMOUR and PERSONA, turning the films being analyzed into stale intellectual constructs—as opposed to the late Samuel Fuller’s explanation of the appeal of film, which (in a cameo in 1965’s PIERROT LE FOU) he famously summed up in one word: emotion.

Vogel was a film professor at the University of Pennsylvania when this book was written, it makes sense that much of it is taken up with text like “There have always existed in the plastic arts tendencies towards forms and images undefiled by representations of reality.” Such highbrow preening can be deadly, especially to film students grinding out subtextual analyses of HIROSHIMA, MON AMOUR and PERSONA, turning the films being analyzed into stale intellectual constructs—as opposed to the late Samuel Fuller’s explanation of the appeal of film, which (in a cameo in 1965’s PIERROT LE FOU) he famously summed up in one word: emotion.

Yet personally I’ve never found the academic bent of FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART too bothersome. Why? Because I don’t pay it much attention, never having read any of Vogel’s essays through fully (or even partially). It’s a testament to the richness of this three ring circus of a book that the reviews and stills are more than enough on their own to make for a satisfying reading experience.

From a marketing standpoint the book was quite successful, especially in the slow-moving category of film texts (take it from one who once worked in a bookstore: such books aren’t what you’d call hot sellers). It’s gone through several printings over the decades, and directly inspired at least one subsequent volume.

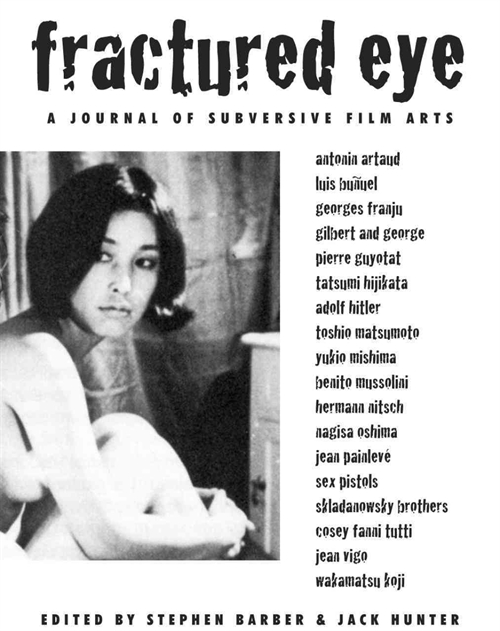

To be sure, imitating the unique-to-itself FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART is a difficult-if-not-impossible feat. The late UK-based Creation Books, however, replicated its distinctive title font on the covers and spines of two of its publications, THE AGE OF GOLD by Robert Short and ANARCHY AND ALCHEMY by Ben Cobb, and its text in the 2012 anthology FRACTURED EYE, which contained the familiar-sounding subtitle A JOURNAL OF SUBVERSIVE FILM ARTS.

To be sure, imitating the unique-to-itself FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART is a difficult-if-not-impossible feat. The late UK-based Creation Books, however, replicated its distinctive title font on the covers and spines of two of its publications, THE AGE OF GOLD by Robert Short and ANARCHY AND ALCHEMY by Ben Cobb, and its text in the 2012 anthology FRACTURED EYE, which contained the familiar-sounding subtitle A JOURNAL OF SUBVERSIVE FILM ARTS.

Edited and largely written by Stephen Barber and “Jack Hunter” (actually Creation founder James Williamson), FRACTURED EYE’s 119 pages cover subjects like the Vienna Action films (also covered in FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART), Kenneth Anger, Koji Wakamatsu’s SHOJO GEBA GEBA, Luis Bunuel’s LAS HURDES and the pioneering film exhibitionists Max and Emil Skladanowsky (an essay reprinted in Senses of Cinema), accompanied by a wealth of outrageous stills. Overall it’s a pleasing enough concoction for adventurous film buffs, but can’t hope to compete with its inspiration.

The bad news? FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART appears to have had its final printing in 2005, meaning this now out of print book is a bonafide Collector’s Item, and tends to fetch unreasonably high prices on the collector’s market. If there are any plans for a reprint on the horizon I’m not aware of them.

Admittedly, I have no idea how Vogel’s text might resonate with a contemporary reader. Part of its appeal back when I was first introduced to it was the fact that the majority of the films it covered were out of reach; it truly was, as a back cover blurb by Luis Bunuel states, “an intense garden with the inducement of a fruit longtime forbidden.” Nowadays that “fruit” is no longer forbidden, being readily available, in most cases, for free on YouTube and other streaming sites. Yet I’m going to persist in recommending FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART to one and all, as it’s among the few books I’d categorize as truly essential.