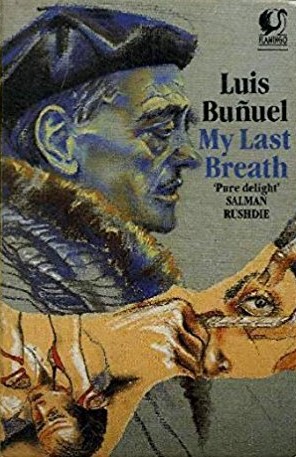

By LUIS BUNUEL (Flamingo; 1982/85)

By LUIS BUNUEL (Flamingo; 1982/85)

This was the final testament of Luis Bunuel, one of the world’s great troublemakers. Born in the year 1900 in the rural Spanish village of Calendra, Bunuel went on to become a member of the surrealist party in France during the late 1920s, and from there became a world renowned—if notoriously impish and controversial—filmmaker. His brand of surreal cinema, in fact, became so iconic that a term was invented to describe it—“Bunuellian”—that’s become nearly as ubiquitous as “Kafkaesque.” This enjoyable “Semiautobiography,” published a year prior to Bunuel’s death, showcases him in highly subdued and contemplative form—a far cry from the irrepressible rabble-rouser he once was.

This enjoyable “Semiautobiography,” published a year prior to Bunuel’s death, showcases him in highly subdued and contemplative form—a far cry from the irrepressible rabble-rouser he once was.

Bunuel does at least include two extended reminiscences by his sister Conchita, who captures his highly idiosyncratic and gregarious personality better than he himself does. Conchita’s recollections are among the many digressions and asides that recur throughout the book, for which Bunuel repeatedly apologizes but still insists on including them because, he claims, they accurately reflect his thought processes. Among those digressions are lengthy chapters about Bunuel’s love of bars, the importance of dreams and reveries, his many (platonic) love affairs and the difficulties of old age (“I’ve begun to complain about my legs, my eyes, my head, my lapses of memory, my weak coordination…The enemy is everywhere, and I’m painfully conscious of my decrepitude”).

Conchita’s recollections are among the many digressions and asides that recur throughout the book, for which Bunuel repeatedly apologizes but still insists on including…

Still, Bunuel manages to relate his life story in reasonably precise chronological order, starting with his childhood in Calendra. In this tiny community, where “the Middle Ages lasted until World War I,” Bunuel was raised a staunch Catholic but around age fourteen turned away from “this warm, protective religion.” He attended the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid during the years 1917-1925, where he came into contact with Federico Garcia Lorca and Salvador Dali, with whom Bunuel formed a close—though far from lasting—friendship. From there Bunuel decamped to Paris, where he and Dali fell in with the surrealists, who were impressed with Bunuel’s legendary short film UN CHIEN ANDALOU.

Bunuel took to the surrealist worldview immediately, proclaiming it “a coherent moral system that, as far as I could tell, had no flaws. It was an aggressive morality based on the complete rejection of all existing values.” Yet he also acknowledges this worldview had its drawbacks; speaking of the surrealists’ ultimate goals, Bunuel claims they had little to do with artistic success but, rather, “to change the world, to transform life itself. This was our essential purpose, but one good look around is evidence enough of our failure.”

Over the next fifty years Bunuel found himself residing in America, Spain, France and Mexico, where he made a number of classic and not-so-classic films, such as the documentary LAS HURDES (a.k.a. LAND WITHOUT BREAD), THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL, BELLE DE JOUR, the Oscar-winning DISCREET CHARM OF THE BOURGEOISIE and his final film THAT OBSCURE OBJECT OF DESIRE (in which he famously used two separate actresses in one role, apparently “a device many spectators never even noticed”).

Bunuel’s notorious cynicism is evident in quotes like “The symbolic significance of terrorism has a certain attraction for me: the idea of destroying the whole social order, the entire human species” and “Long live forgetfulness, I’ve always said—the only dignity is in oblivion,” and also in his oft-rancorous recollections of various famous figures: Abel Gance is dismissed as “pretentious,” as is Jorge-Luis Borges, while his onetime friend Salvador Dali is taken to task for “his egomania, his obsessive exhibitionism…and his frank disrespect for friendship.” Overall, though, MY LAST BREATH is pretty subdued. That’s not a bad thing, but it does make one yearn to hear from Luis Bunuel’s younger, and much wilder, self.