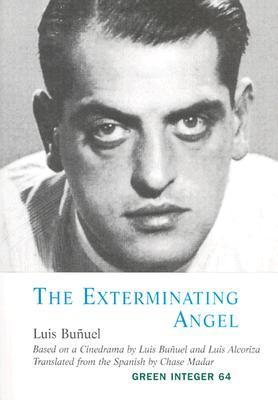

By LUIS BUNUEL, LUIS ALCORIZA (Green Integer; 2003)

By LUIS BUNUEL, LUIS ALCORIZA (Green Integer; 2003)

No, this isn’t a novelization of writer/director Luis Bunuel’s 1962 film EL ANGEL EXTERMINADOR, but, rather, the screenplay for it, written by Bunuel and Luis Alcoriza (and ably translated into English by Chase Madar). The script, it turns out, is a powerful piece of work in its own right, perhaps not the “important work of literature” proclaimed on the back cover, but a document that deserves to be considered on its own merits, independently of the film.

The script, it turns out, is a powerful piece of work in its own right, perhaps not the “important work of literature” proclaimed on the back cover, but a document that deserves to be considered on its own merits, independently of the film.

The story: Nobile, an aristocrat, throws an elaborate dinner party in his swank mansion, a place “furnished with more opulence than good taste.” Before the shindig gets started the servants and maids are compelled to flee the house, followed by the cooks and waiters, all possessed by “a strange need to hurry.” Only the majordomo (or butler) remains. Throughout the ensuing dinner party we’re provided with seemingly superfluous dialogue exchanges that bear close attention because, as a script direction makes clear, “The following dialogue is more important than it seems.”

That sense of apprehension is further delineated in descriptions like this one, about the inexplicable sense of terror that overcomes one of the guests: “Why with terror? She herself wouldn’t be able to explain.” Another, even more significant stage direction alerts us that “Something strange is happening,” which manifests itself in the fact that for some reason none of the guests are able to cross the threshold of the music room, where they retire after leaving the dining room. The music room is much smaller than the other, and the atmosphere in this enclosed space grows poisonous very quickly.

Throughout the ensuing dinner party we’re provided with seemingly superfluous dialogue exchanges that bear close attention because, as a script direction makes clear, “The following dialogue is more important than it seems.”

The horror suffusing this script is certainly present in the finished film, but it’s heightened on the page, where it reaches near Robert Aickman-esque heights of surreal apprehension. So too the social satire, which is far more accentuated than it was onscreen; here again the screen directions make that point clear, taking pains to delineate the fact that the men keep themselves clean shaven throughout the ordeal, and the fact that some of the women guests remove their shoes, as “It is only natural that given their forced inactivity they have unburdened themselves of this garment which impedes the circulation, just like travelers on a long airplane trip.” There’s even an explanation of sorts for the story’s bizarre events in an exterior scene in which a little girl attempts to enter the mansion, only to change her mind because “as soon as the girl was conscious of her actions the same thing happened to her as to the adults.”

The horror suffusing this script is certainly present in the finished film, but it’s heightened on the page, where it reaches near Robert Aickman-esque heights of surreal apprehension. So too the social satire, which is far more accentuated than it was onscreen; here again the screen directions make that point clear, taking pains to delineate the fact that the men keep themselves clean shaven throughout the ordeal, and the fact that some of the women guests remove their shoes, as “It is only natural that given their forced inactivity they have unburdened themselves of this garment which impedes the circulation, just like travelers on a long airplane trip.” There’s even an explanation of sorts for the story’s bizarre events in an exterior scene in which a little girl attempts to enter the mansion, only to change her mind because “as soon as the girl was conscious of her actions the same thing happened to her as to the adults.”

The horror suffusing this script is certainly present in the finished film, but it’s heightened on the page, where it reaches near Robert Aickman-esque heights of surreal apprehension.

Yet ultimately, despite my affection for this book, it is still just a script—a blueprint, that is, with perfunctory descriptions that at times (particularly in the quintessentially Bunuelian dream sequences, which don’t quite work on the page) fall flat. It makes one lament the fact that, outside a few short pieces published in surrealist journals and other publications, Bunuel never wrote much fiction. Based on this publication it seems he had a talent for it, a talent that could definitely have stood to be improved.