In the annals of filmdom there exist few performers more unfettered than the late Klaus Kinski (1926-1991), who appeared in over 250 films during his lifetime, some of them classics though most decidedly not. As an actor Kinski demonstrated a boldness and ferocity that remain unrivalled, even if the films he appeared in didn’t always match his brilliance.

In the annals of filmdom there exist few performers more unfettered than the late Klaus Kinski (1926-1991), who appeared in over 250 films during his lifetime, some of them classics though most decidedly not. As an actor Kinski demonstrated a boldness and ferocity that remain unrivalled, even if the films he appeared in didn’t always match his brilliance.

In my view, however, Kinski’s most memorable accomplishment was his autobiography, an astounding cavalcade of madness and perversion. Told in blistering present tense prose, it’s very likely the most outrageous celebrity memoir of all time, having inspired two high profile lawsuits and a documentary rebuttal by the German filmmaker Werner Herzog.

Herzog’s film, released in 2000, is called MY BEST FIEND (or MEIN LIEBSTER FEIND). In it the flamboyant Herzog, once an enfant terrible and now a thoughtful middle-aged man, details his volatile relationship with Kinski over the course of the five films they made together (AGUIRRE: THE WRATH OF GOD, NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE, WOYZECK, FITZCARRALDO and COBRA VERDE). Herzog is vocal about Kinski’s talent (“People like Brando are just kindergarten compared to Kinski”), and reveals that despite the fact that the two were often at odds—both allegedly planned to have the other killed at some point—they shared a bond of sorts (in a 1985 Playboy profile Kinski admitted Herzog was “a less big asshole than the others”). The latter was nonetheless always frank about Kinksi’s lunacy, and in MY BEST FIEND includes footage of the man spouting off during the filming of FITZCARRALDO (1982).

This was by no means the only such outrage perpetrated by Kinski, whose on-set demeanor remains the stuff of legend—schlock filmmaker David Schmoeller, who directed Kinski in 1986’s CRAWLSPACE, made a short documentary entitled “Please Kill Mr. Kinski” about the on-set antics of his star. In MY BEST FIEND Herzog reveals that Kinski’s behavior on their final collaboration COBRA VERDE (1987) grew so unbearable he vowed never to work with him again. Herzog also takes time to respond directly to Kinski’s memoir, apparently a “work of fiction.”

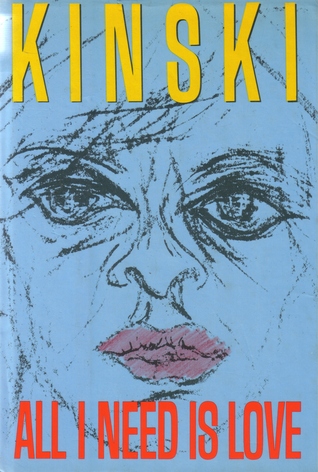

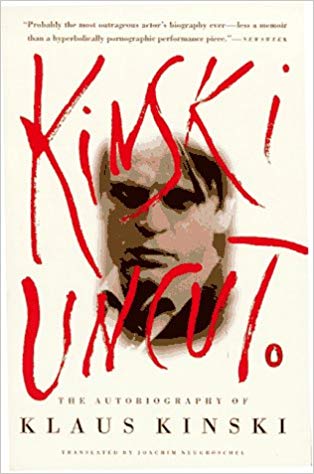

But here’s the thing: the book, initially titled ICH BIN SO WILD NACH DEINEM ERDBEERMUND (I’M SO CRAZY ABOUT YOUR STRAWBERRY MOUTH), first appeared in Germany in the mid seventies. Since then two widely differing English versions have appeared: ALL I NEED IS LOVE, published by Random House in 1988, and KINSKI UNCUT, put out by Viking in 1996. Of the two the obvious pick would seem to be the latter, as it runs approximately fifty pages longer that the other and has the word Uncut in the title (which allegedly refers to Kinski’s penis), but the case isn’t as cut-and-dried as it might seem. More on that in a bit.

First let’s take a look at the scabrous content of these books. They posit that Kinski grew up in a dirt-poor family who were homeless for long periods, having to sleep on subway grates to keep warm (never mind that Herzog claims Kinski was actually the son of a wealthy pharmacist). The young Kinski apparently lost his virginity to his older sister, and ended up shtupping his mother as well (as you might guess, Kinski’s surviving relatives were none too happy with his book).

As a grown-up Kinski claims to have spent time in jail, in a mental institution and the German military—and nearly executed for desertion. Then there are the accounts of Kinski’s experiences as an actor, an occupation he detested but which he was extremely good at. “I am like a wild animal born in a zoo” he writes, “but where a beast would have claws, I was born with talent.” That talent, according to Herzog, was vetted by countless hours of disciplined training, though Kinski portrays it as something God-given over which he had no control, “something you have to try and live with—until you learn how to free yourself.”

Kinski’s talents provided him with the means to afford a fleet of fancy cars, opulent homes and a never-ending succession of willing sexual partners. The sexual content of ALL I NEED IS LOVE and KINSKI UNCUT is positively mind-numbing, recounted at a rate of (at least) 3 or 4 escapades per page (Herzog again: the sexual content was “grossly exaggerated”).

On those rare occasions when he’s not fucking, Kinski rages against damn near everybody he’s ever met and/or worked with, most notably Mr. Herzog, a “humorless, mendacious, stubborn, narrow-minded, pretentious, unscrupulous, bumptious, spiritless, depressing, boring, and sickening” individual (Herzog says he helped Kinski come up with adjectives). Polish filmmaker Andrzej Zulawski is chided for his “intellectual jerking off,” Federico Fellini and Claude Lelouch are remembered as tightwads with whom Kinski refused to work, and LAST TANGO IN PARIS’ Maria Schneider as a pathetic junky.

Kinski also brags of turning down an offer to play the villain in RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK because the script was “the same tired old shit” (he instead appeared in the British sleazer VENOM, not exactly a model of originality). Nor are his admirers cut any slack—of his fan mail Kinski has this to say: “I throw the stuff in the garbage.”

Kinski’s existence, in short, was a tortured one, and resulted in strained relationships with his three children (all from different mothers) Pola, Nastassja (initially Nastassia) and Nanhoi. I’d say Nanhoi, born in 1976, had it the roughest, as he was the focus of his father’s wildly obsessive, all-consuming love. It seemed that as he got older Kinski’s inner torment deepened to the point that his sexcapades no longer sufficed to keep it at bay, so he made Nanhoi the center of his existence, positing that “I live solely for my son, whom I love beyond all earthly and heavenly things,” and, even more tellingly, “Nanhoi’s love will redeem me from my Hell on Earth.”

Kinski’s intense focus on Nanhoi was not lost on Nastassja, who as a child reportedly had to stop her mom from committing suicide due to her father’s compulsive womanizing, and who was abandoned by him at age seven. She gives vent to her feelings of abandonment late in the text, in a poignant exchange with her father—who admits that “I wasn’t by her side when she needed me.”

Upon Kinski’s 1991 death Nanhoi was reportedly the only person who attended his funeral. Nastassja for her part offered the following tribute: “When he died I had a moment of grief that lasted about five minutes. It was very intense, then never again…I think it was because he caused us too much pain.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, Nastassja has led a personal and professional life nearly as fraught as that recounted in her father’s text.

At times that text descends to tabloid gossip level, as when Kinski recalls a woman telling him she was eaten out by Marlene Dietrich (who sued), and meets Roman Polanski trolling for young girls. At others it feels like a morbid horror fantasy, with Kinski claiming to have encountered an actress wearing a coat made from aborted human fetuses. But the tone throughout is strong and unwavering, a propulsive evocation of ecstasy and disgust, bravado and self-loathing, genius and madness.

The factuality of Kinski’s memoir may be questionable, but one area where I believe he was entirely truthful was in his unblinking self portrait, which is as ruthlessly delineated as anything else he describes. Kinski reveals himself as an impossibly cranky, needy, misanthropic and very likely psychotic individual—which according to nearly everyone who knew him was how he actually was.

After reading ALL I NEED IS LOVE back in 1988 I eagerly searched out memoirs by two other debauched European celebrities, Roger Vadim (MEMOIRS OF THE DEVIL) and Roman Polanski (ROMAN), hoping for a similar level of candor. Needless to say I was disappointed, and made forcibly aware of just how unique Kinski’s autobiography truly is. His book is free of boastful self-aggrandization (unlike Vadim’s) and nor is it a desperate attempt at clearing his name (unlike Polanski’s). Rather, with his memoir Kinski sees to be saying, in essence, “This is who I am—take it or leave it!”

In discussing either of the English language versions of Klaus Kinski’s memoirs it’s imperative to specify which, as both are quite distinct. I’ll take this opportunity to point out many of the differences between the two books, but will first attempt to unravel the knot of hearsay and misinformation surrounding the respective publications of ALL I NEED IS LOVE and KINSKI UNCUT.

The misinformation begins with the books themselves. The copyright page of ALL I NEED IS LOVE claims the text was taken from an “unpublished manuscript,” even though that manuscript had already been published in Europe. The jacket info on the hardcover edition of KINSKI UNCUT is even more misleading, claiming that the original American edition was “withdrawn prior to publication.”

That last point is total nonsense, yet many continue to believe it. It’s the reason, I’m sure, that online booksellers are currently offering secondhand copies of ALL I NEED IS LOVE at outrageous prices. Yet back in 1988 the book was quite easy to find, and over the years I’ve come across quite a few copies at libraries and used book stores (Ethan Hawk is even seen reading it at the beginning of Richard Linklatter’s BEFORE SUNRISE).

What seems to have happened is this: Nastassja Kinski threatened Random House with legal action because, allegedly, in ALL I NEED IS LOVE her father hints at an incestuous coupling on the set of TESS, and in response Random House canceled the remainder of the book’s print run. That seems to be the long and the short of it.

In KINSKI UNCUT the offending passage was toned down…which would seem to make the former publication the true “uncut” account. Not quite.

KINSKI UNCUT is in fact the more complete of the two books, and contains several passages that don’t appear in ALL I NEED IS LOVE. These include a whore’s lengthy mid-book oration, in which she admits that “sometimes I lay awake at night and couldn’t sleep because I was thinking that somewhere out there some horny, raging hard-on is hunting a pussy like mine,” and the concluding passages, which take the narrative several years beyond where the previous book ends. But is KINSKI UNCUT truly “Uncut?” Once again the answer is: Not quite.

KINSKI UNCUT is in fact the more complete of the two books, and contains several passages that don’t appear in ALL I NEED IS LOVE. These include a whore’s lengthy mid-book oration, in which she admits that “sometimes I lay awake at night and couldn’t sleep because I was thinking that somewhere out there some horny, raging hard-on is hunting a pussy like mine,” and the concluding passages, which take the narrative several years beyond where the previous book ends. But is KINSKI UNCUT truly “Uncut?” Once again the answer is: Not quite.

ALL I NEED IS LOVE may be shorter than KINSKI UNCUT, but it too contains much that’s absent from the latter book, including a reminiscence of Kinski getting pissed on as a child and another of playing tennis on the set of Jess Franco’s JACK THE RIPPER until he can “neither walk nor stand.” ALL I NEED IS LOVE is further distinguished by the astonishing bluntness of Kinski’s profanity-laden prose.

KINSKI UNCUT is plenty blunt in its own right, but as translated by Joachim Neugroschel it’s also quite wordy and even somewhat chaste, at least in comparison with the earlier volume, which was translated by Kinski himself. The differences between the two books are striking.

Neugroschel renders a sentence as “some cattle driver in the crew” that Kinski translates as “some sadistic shit of a director.” In Neugroschel’s translation Werner Herzog is called a “very slow blab machine,” and in Kinki’s a “bullshit machine.” In the Neugroschel version Kinski grows tired of a fuckmate’s babbling and so “I kick her out,” while Kinski’s rendering of the same sentence is decidedly more visceral: “I can’t get a hard-on anymore.”

Such differences may seem inconsequential, but they add up. So too the paragraph structure. The whole thing is related entirely without chapter breaks, in sharp blocks of more-or-less self-contained text. In ALL I NEED IS LOVE said text blocks are shorter than those of the succeeding book, and the whole thing moves much faster. The effect is harshly poetic, and often downright hallucinatory.

One passage of ALL I NEED IS LOVE puzzled me for some time: on page 217 there’s an unmotivated parenthetical aside that reads “(I don’t want to talk about GOLDEN NIGHT).” It only came clear upon reading the corresponding section of KINSKI UNCUT, in which Kinski bemoans the ordeal of working on a French thriller called NUIT D’OR, or GOLDEN NIGHT. It seems that with ALL I NEED IS LOVE Kinski wasn’t merely translating his original manuscript, but subtly responding to and obliquely rewriting it.

Obviously you’ll need to read both books in order to fully grasp this and other pertinent facts. I’m pleased I’ve had the chance to read and compare ALL I NEED IS LOVE and KINSKI UNCUT, as both are classics. As to which I prefer, I think that should be obvious, and not just because one has been with me far longer than the other.

Reading KINSKI UNCUT is akin to being led by the hand through a vortex and rage and excess, whereas in ALL I NEED IS LOVE the reader is thrust kicking and screaming into the very heart of the maelstrom. KINSKI UNCUT is a bruising experience, certainly, but ALL I NEED IS LOVE is positively lacerating. It’s also among the greatest sensory assaults in all literature, outdoing the likes of Artaud, Celine and Sartre in nastiness and nausea. To this day I’ve never read anything else like it.

Of course the sad reality is that you’re unlikely to find a copy of ALL I NEED IS LOVE at a reasonable price. For that matter, KINSKI UNCUT has also become a pricey collector’s item. Truthfully, there’s little chance of either book coming back into print anytime soon…but we can always hope.