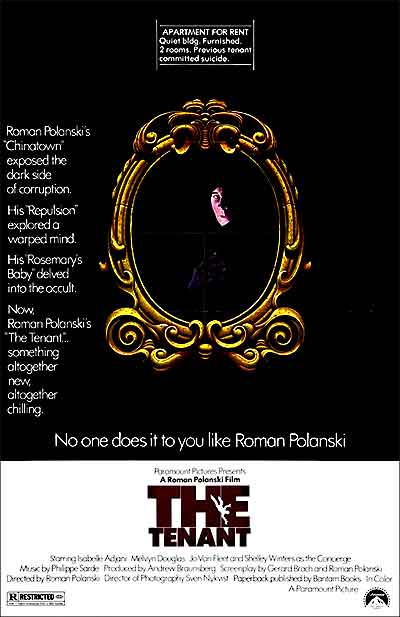

This Roman Polanski thriller approaches greatness and, but for some questionable artistic choices, nearly achieves it. As it is, THE TENANT is a powerfully eccentric study of paranoia and obsession shot through with tension, claustrophobia and a jolting streak of black humor.

This Roman Polanski thriller approaches greatness and, but for some questionable artistic choices, nearly achieves it. As it is, THE TENANT is a powerfully eccentric study of paranoia and obsession shot through with tension, claustrophobia and a jolting streak of black humor.

THE TENANT was adapted from a 1964 novel by the French surrealist Roland Topor (who co-founded the infamous “Panic” movement with Alejandro Jodorowski and Fernando Arrabal and designed the sci fi animation classic FANTASTIC PLANET) and photographed by the great Sven Nykvist (Ingmar Bergman’s cinematographer of choice). It was, alas, a box office failure and suffered a decidedly hostile reception at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival, where it was written off as a poor attempt at aping the style and content of ROSEMARY’S BABY, one of Polanski’s most successful films. The failure of THE TENANT seems to have scarred Polanski irretrievably, as he’s come to regard it as a failed experiment in genre mixing. In his own words: “The picture labors under an unacceptable change of mood halfway through…a tragedy must remain a tragedy; a comedy that turns into a drama almost always fails.”

The failure of THE TENANT seems to have scarred Polanski irretrievably, as he’s come to regard it as a failed experiment in genre mixing.

In fact THE TENANT, while undeniably flawed, remains one of Polanski’s more interesting films. Its mix of humor and horror was unprecedented at the time and, contrary to Polanski’s subsequent views, works quite well for the most part. Furthermore, the formula pioneered in THE TENANT has gone on to be utilized with great success by filmmakers like David Lynch and the Coen Brothers (whose BARTON FINK, a film greatly admired by Polanski, is remarkably TENANT-like in many aspects).

Trelkovsky is a mousy young man who moves into a Parisian apartment building presided over by a crotchety old man who loves to continuously remind his tenants of how difficult it is to find a place to live and that in doing so he’s providing an incredibly generous service. Trelkovky’s apartment, it turns out, is a small, shabby hole whose previous tenant, a young woman, attempted suicide by jumping out the window. Trelkovsky goes to visit the woman in a hospital, where he finds a decrepit figure with bandages covering her entire body. He also meets Stella, the woman’s best friend, who for some reason takes an immediate shine to Trelkovsky.

Trelkovsky is a mousy young man who moves into a Parisian apartment building presided over by a crotchety old man who loves to continuously remind his tenants of how difficult it is to find a place to live and that in doing so he’s providing an incredibly generous service. Trelkovky’s apartment, it turns out, is a small, shabby hole whose previous tenant, a young woman, attempted suicide by jumping out the window. Trelkovsky goes to visit the woman in a hospital, where he finds a decrepit figure with bandages covering her entire body. He also meets Stella, the woman’s best friend, who for some reason takes an immediate shine to Trelkovsky.

Its mix of humor and horror was unprecedented at the time and, contrary to Polanski’s subsequent views, works quite well for the most part.

Back in the apartment things grow increasingly strange. In the bathroom across from Trelkovsky’s room people stand motionless for hours on end. One morning Trelkovsky spills a lot of trash in the apartment stairwell but when he comes back to clean it up finds it has mysteriously disappeared. His neighbors are apparently extremely sensitive to sound and register endless complaints with the management about Trelkovsky and his alleged noise-making. He’s further alienated from his fellow tenants when he refuses to sign a petition to force a woman living upstairs with her crippled daughter to vacate the premises.

As the atmosphere grows increasingly stifling, Trelkovsky begins to suspect that his neighbors are plotting against him. Pretty soon he finds himself wearing the clothes of the previous tenant and smearing make-up on his face, and realizes the “truth”: that his fellow tenants are trying to change him into his apartment’s former occupant. He turns to Stella for help, but comes to the conclusion that she’s in on it too—there’s nowhere to turn, it seems, except out his apartment window, in the manner of its previous occupant…

As he did in ROSEMARY’S BABY, Roman Polanski follows his source material extremely closely in THE TENANT, complete with dialogue that’s often word-for-word the same as that of the Roland Topor novel. Polanski does, however, depart from the text in one significant—and highly questionable—aspect: he often undercuts the protagonist’s experiences by alternating the “actual” events with Trelkovsky’s delusions. Thus a woman choking Trelkovsky is “actually” invisible, just as the sinister appearance of the apartment manager through a peephole is “actually” a door-to-door salesman. Polanski’s puzzling insistence on accentuating the fact that the drama is all in Trelkovsky’s head feels like a cynical attempt at “explaining” what should have been left up to viewers to decide for themselves (it’s the type of thing I’d expect a Hollywood studio executive to force a filmmaker into after a bad test screening) and only serves to distance one from the action.

Thankfully the film is superbly made; as usual, Polanski’s camerawork and editing are top notch, with an unerring eye for detail and an atmosphere that positively drips with foreboding, unease and a singularly perverse sense of humor.

Thankfully the film is superbly made; as usual, Polanski’s camerawork and editing are top notch, with an unerring eye for detail and an atmosphere that positively drips with foreboding, unease and a singularly perverse sense of humor. He pulls off quite a few bravura moments herein, most notably the stunning opening pan around the exterior of Trelkovsky’s apartment building. Polanski also delivers a flawless performance in the lead role, his first major acting part since THE FEARLESS VAMPIRE KILLERS; as the nerdy Trelkovsky he’s funny, appropriately mousy and isn’t afraid to make himself look like a complete buffoon—indeed, he seems to positively relish doing so throughout.

See Also: REPULSION

Vital Statistics

THE TENANT (LE LOCATAIRE)

Paramount Pictures

Director: Roman Polanski

Producer: Andrew Braunsberg

Screenplay: Roman Polanski, Gerard Brach

(Based on a novel by Roland Topor)

Cinematography: Sven Nykvist

Editing: Francois Bonnot

Cast: Roman Polanski, Isabelle Adjani, Melvyn Douglas, Jo Van Fleet, Bernard Fresson, Shelley Winters, Lila Kedrova, Claude Dauphin, Claude Pieplu, Rufus, Romain Bouteille, Jacques Monod, Patrice Alexsandre, Michel Blanc