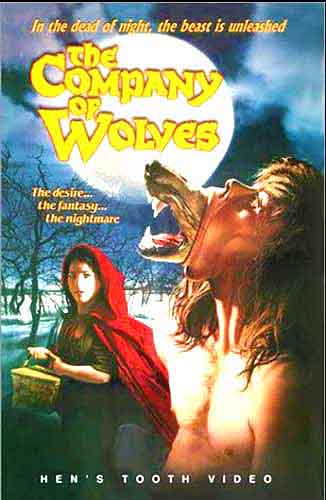

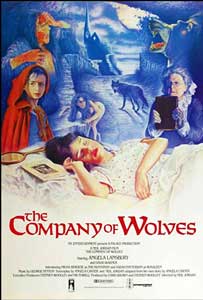

The second feature by Neil Jordan was this 1984 British production, adapted from a story by Angela Carter. That story hails from the 1979 collection THE BLOODY CHAMBER, consisting of adult-oriented fairy tale inversions; in the case of “THE COMPANY OF WOLVES,” the fairy tale being inverted was that of Little Red Riding Hood. The film adaptation, a highly elliptical affair that mixes outright surrealism with traditional horror movie trappings, appears to have been geared toward the cult circuit, and that’s just where it ended up, being (to quote Paul Schrader) too arty for the blood crowd and too bloody for the art crowd.

The second feature by Neil Jordan was this 1984 British production, adapted from a story by Angela Carter. That story hails from the 1979 collection THE BLOODY CHAMBER, consisting of adult-oriented fairy tale inversions; in the case of “THE COMPANY OF WOLVES,” the fairy tale being inverted was that of Little Red Riding Hood. The film adaptation, a highly elliptical affair that mixes outright surrealism with traditional horror movie trappings, appears to have been geared toward the cult circuit, and that’s just where it ended up, being (to quote Paul Schrader) too arty for the blood crowd and too bloody for the art crowd.

(to quote Paul Schrader) too arty for the blood crowd and too bloody for the art crowd.

Neil Jordan’s interest in lycanthropy was first reared in his 1983 novella THE DREAM OF A BEAST (Jordan having been a novelist before becoming a filmmaker), a dreamlike, symbolism-packed treatment of a suburban man’s transformation into a beast. In THE COMPANY OF WOLVES that subject is taken much further. The ambition is laudable, albeit perhaps a bit overmuch for a second time director—even one as talented as Neil Jordan.

The film begins with Rosalie, a young girl living in a stately mansion, having a dream. In this dream she resides in an enchanted forest where birds’ eggs hatch infant figurines and wolves and toads are ever-present (wolves being symbolic of nonconformity and toads of transformation). Here Rosalie, who wears a red cloak whenever she goes out, divides her time between the home of her parents and that of her superstitious grandmother.

Drama occurs when Rosalie’s older sister is killed by, the grandmother claims, a wolf that’s “hairy on the outside.” But as the old woman warns Rosalie, the most dangerous wolves are those that are hairy on the inside. To illustrate this she relates a story we see dramatized, involving a young woman whose estranged husband transforms into a werewolf upon returning home and finding two children he didn’t sire.

The transformation motif repeats itself in a story Rosalie tells about the guests of a lavish ball turning into wolves that trample a peacock (peacocks being symbolic of salvation), and the paw of a just-killed wolf brought home by her father that transforms into a human hand. One day when Rosalie heads off to see her grandmother she meets a strange man to whom she finds herself attracted, thus threatening to end her little girl status for good. That threat is furthered when the guy heads to gramma’s house and kills the old woman, then attempts to seduce Rosalie when she arrives. She ends up shooting him with a rifle, triggering yet another transformation, and an ending that, in the words cartoonist/film reviewer Gahan Wilson, “suggests that maturity doesn’t work, love fails, and the boogeyman gets you after all.”

“…maturity doesn’t work, love fails, and the boogeyman gets you after all.”

The young Neil Jordan assembled an impressive cast for this film, including Angela Lansbury, David Warner and an uncredited Terence Stamp. The crew is equally auspicious, with big names like production designer extraordinaire Anton Furst and special effects designer Christopher Tucker (of THE ELEPHANT MAN and QUEST FOR FIRE), who here provides several amazingly elaborate transformation effects (which were greatly played up by the film’s US distributors). It’s a bit surprising, then, that the film has a cheap veneer redolent of the 1980s (as evinced by the telltale synthesizer score), with patently unreal stage-bound scenery and BBC telefilm worthy lighting.

Jordan’s instincts, at least, were strong. Turning his back on commercial considerations in favor of a more surreal, dream-powered treatment, while still keeping the expected B-movie elements in play, was the right call for this material. Yet that material may have been inherently flawed, seeing as how it was adapted from a short story (always a dicey proposition), and a pretty nonlinear one. This means that from a storytelling standpoint the film is never remotely satisfying, feeling like a collection of self-contained episodes in search of a unified whole. That’s an issue, I feel, the experienced Neil Jordan might have able to work his way around, but for the youthful Jordan it represented an insurmountable obstacle.

Jordan’s instincts, at least, were strong. Turning his back on commercial considerations in favor of a more surreal, dream-powered treatment, while still keeping the expected B-movie elements in play, was the right call for this material. Yet that material may have been inherently flawed, seeing as how it was adapted from a short story (always a dicey proposition), and a pretty nonlinear one. This means that from a storytelling standpoint the film is never remotely satisfying, feeling like a collection of self-contained episodes in search of a unified whole. That’s an issue, I feel, the experienced Neil Jordan might have able to work his way around, but for the youthful Jordan it represented an insurmountable obstacle.

Vital Statistics

THE COMPANY OF WOLVES

ITC Entertainment

Director: Neil Jordan

Producers: Chris Brown, Stephan Wooley

Screenplay: Angela Carter, Neal Jordan

(Based on a story by Angela Carter)

Cinematography: Bryan Loftus

Editing: Rodney Holland

Cast: Angela Lansbury, Graham Crowden, Brian Glover, Kathryn Pogson, Stephen Rea, Tusse Silberg, David Warner, Micha Bergese, Sarah Patterson