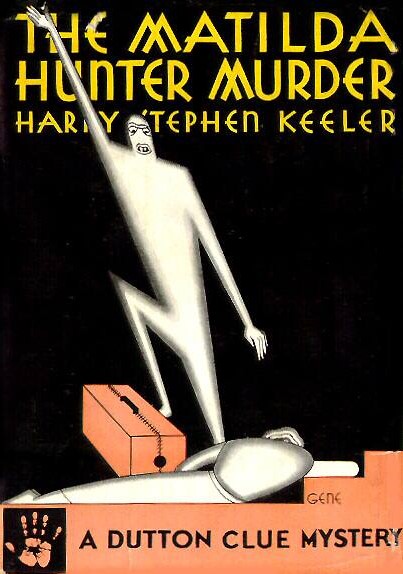

By HARRY STEPHEN KEELER (Dutton; 1931)

By HARRY STEPHEN KEELER (Dutton; 1931)

This was the tenth novel by Harry Stephen Keeler, and the second longest. The first was THE BOX FROM JAPAN (1932), which is often cited as the lengthiest mystery novel ever written; THE MATILDA MURDER HUNTER, then, is the next longest. With that in mind the novel’s major failing shouldn’t be too difficult to figure out: it’s too damn long.

THE MATILDA MURDER HUNTER, furthermore, marked the debut appearance of the eccentric Sherlock Holmesian detective Tuddleton Trotter (who features in two subsequent Keeler mysteries), although he doesn’t turn up until around page 200. Until then we get the altogether nutty story of Jerry Evans, a young man attempting to negotiate the particulars of an especially complex will (a Keeler trademark) who becomes caught up in a drama involving what would appear to be an apparatus, carried in a black satchel, capable of firing some kind of radiation beam that kills some hapless animals and Jerry’s own aunt before completely destroying the building in which the latter resided.

Keeler has been credited by some with predicting the effects of nuclear energy, but the alleged particle beam described here isn’t nuclear. Nor is it the true cause of the deaths and conflagration, as proven by Tuddleton Trotter, whose very meticulous investigation into the crimes overtakes the book’s remaining 500-plus pages. Not to give anything away, but as any habitual Keeler reader can predict, the explanation involves a lot of outrageous coincidences and at least one bizarre contraption (would you believe a syringe-tipped cane?) in a solution whose particulars are even wackier than those of the initial crime.

The book is, once again, very long. The bloat of THE BOX FROM JAPAN can be blamed on the science fiction detailing required by the futuristic setting, but the non-SF MATILDA MURDER HUNTER has no such excuse. It’s a novel that takes its sweet time, with lengthy ruminations on the fundamentals of taxi dancing (as enumerated by Trotter’s chat with a practitioner), astigmatism (laid out in a morgue-set passage in which Trotter slits a corpse’s eyelids) and other arcane matters. And yes, the foreign dialects in which Keeler specialized are here in abundance, often lasting for entire chapters, and, for added political incorrectness, often spoken by black characters (including one named Lilywhite). Lacking is the page-turning exuberance of its author’s best work, in a novel that without all the excess flab might have stacked up as an above-average Keeler, but with it falls far below standard.