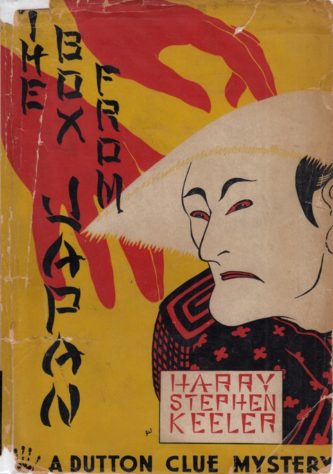

By HARRY STEPHEN KEELER (E.P. Dutton & Co.; 1932)

By HARRY STEPHEN KEELER (E.P. Dutton & Co.; 1932)

This is it: the magnum opus of the late Harry Stephen Keeler, the world’s most bizarre mystery novelist. Clocking in at 765 pages, THE BOX FROM JAPAN is the longest of Keeler’s novels, and quite probably the lengthiest mystery novel ever written. Of course it’s not “just” a mystery, having more than a touch of science fiction in its setting, the far-off year 1942. This makes for a lot—and I do mean lot—of excess description and scene-setting, as Keeler takes his world building quite seriously. Later Keeler excursions in sci fi like THE WHITE CIRCLE and STRANGE JOURNEY would further prove this, but THE BOX FROM JAPAN hails from his earlier, more fertile period, when Keeler was immersed in the so-called “webwork” mysteries in which he specialized. This novel contains all of Keeler’s webwork hallmarks in addition to the futuristic detail, making for a double-tiered mind-boggler.

The story involves Carr Halsey, a Chicago newspaper reporter who impulsively purchases an odd box at an unclaimed mail auction. The box, it turns out, is a Japanese-made contraption intended to transport human skulls, although upon opening it Halsey finds only a bottle of blue liquid. It initially seems a pretty benign acquisition, but Halsey’s existence is quickly turned upside down, as a number of powerful people are after the contents of the box from Japan, and will stop at nothing, including murder, to get it.

Further plot strands include a lucrative will Halsey may or may not inherit, the details of which are far too involved to go into here (and anyway, I’ll confess I skimmed the particulars of said will). And then there’s the futuristic detail, which Keeler lays out in extremely expansive detail. In this novel’s “Flying ‘40’s” Japan is at war with England, Mexico is embroiled in a revolution, 3-D television is a reality, a year lasts 13 months, guillotines have been installed in place of electric chairs in many states, police travel via gyrocopters and oxygen-intolerant envelopes are a thing. We also learn of The Man They Could Not Hang, although this particular man bears no relation to the real MTCNH (one John Babbacombe Lee), being named, appropriately, John Hangless, and the subject, apparently, of a popular song, the sheet music for which “lies today in thousands of dusty music cabinets.”

Keeler buffs will find quite a few of his lifelong obsessions aired in these pages. The Chicago setting is a Keeler hallmark, while his love of skulls and strange wills are certainly given prominence, as is his fascination for all things Japanese (England, Mexico, Australia and Canada also figure heavily in these pages) and, on a related note, his penchant for foreign accented English dialogue that would likely be called politically incorrect, if not outright racist, nowadays (example: “Only I vass t’inking dot I coot send my men chust the same—unt de fool police voot chust t’ink it vass some of our gahngsters–schweinhünde vot dey are, dose gahngsters!”).

Such multi-faceted lunacy cold only have emerged from the mind of Harry Stephen Keeler. Exasperating, outrageous and irredeemably nutty this novel may undeniably be, but just as undeniable is the cockeyed genius suffusing its every page. Just be advised that for you Keeler neophytes THE BOX FROM JAPAN is probably not a good place to start!