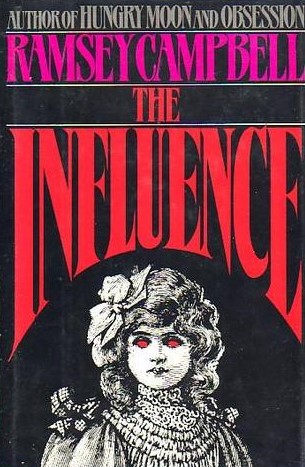

By RAMSEY CAMPBELL (Macmillan; 1988)

By RAMSEY CAMPBELL (Macmillan; 1988)

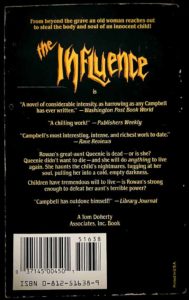

Regarding THE INFLUENCE, I find I’m unable to think about it without flashing back to an especially pissy Fangoria review by David Kuehls. His ire, mind you, wasn’t directed at THE INFLUENCE itself but, rather, the enthusiastic cover blurbs by John Farris (“one of the best novels I’ve read in quite a while”), Clive Barker (“Campbell at the height of his power to terrify and disturb”) and James Herbert (“For me, it’s Ramsey Campbell’s finest”); Kuehls’s review concluded by questioning if horror writers are “members of one big back-slapping fraternity who complement each other on their golf rounds, regardless of whether they shoot under or over par?”

Kuehls’s review concluded by questioning if horror writers are “members of one big back-slapping fraternity who complement each other on their golf rounds, regardless of whether they shoot under or over par?”

Truthfully I’ve often wondered that myself, although this isn’t the place to ponder Kuehls’s query. I will, however, offer an opinion as to why Farris, Barker and Herbert were so admittedly overenthusiastic: because this book, unlike Campbell’s preceding novels, is mercifully short and contained. It followed 1986’s punishing THE HUNGRY MOON, essentially the NIGHT LAND of eighties horror novels (meaning it was a brilliantly conceived and imagined but profoundly long-winded and lugubrious read). Thus, to longtime Campbell readers the focused and compact INFLUENCE was quite refreshing, and perhaps seemed far better than it actually was.

…the focused and compact INFLUENCE was quite refreshing, and perhaps seemed far better than it actually was.

The novel often reads like a Ramsey Campbell Greatest Hits package, with quite a few elements that will be familiar to readers of his previous novels and stories. In the character of the irascible Queenie it features a thoroughly unpleasant old person of a type that tends to recur in Campbell’s fiction (and reached its apotheosis in THE FACE THAT MUST DIE), while Queenie’s grand-niece Rowan, who becomes possessed by the old bag’s unquiet spirit after she kicks, is cut from the same cloth as the children in jeopardy of THE NAMELESS and NIGHT OF THE CLAW, and the powerfully evoked descriptions of Rowan seeing her own possessed body directly recall similar passages in THE PARASITE.

Another Campbell trademark is the strained family dynamic that powers the narrative. The tight-knit Faraday clan orbits Queenie, even though they all hate her, with Rowan’s parents Alison and Derek forced by financial problems to live with the hag in her creepy Wales home. They inadvertently assist in the undead Queenie’s evil designs via a discussion about how their daughter’s birth was accidental and she was unwanted—Campbell, in direct contrast to many of his horror writer contemporaries, has no problem with flawed protagonists—which Rowan overhears. This only increases the apprehension she feels after Queenie’s death, which allows the latter to manipulate and take control of Rowan’s emotions in the form of Vicky, an unearthly little girl who befriends Rowan, and eventually overtakes her altogether.

Another Campbell trademark is the strained family dynamic that powers the narrative. The tight-knit Faraday clan orbits Queenie, even though they all hate her, with Rowan’s parents Alison and Derek forced by financial problems to live with the hag in her creepy Wales home. They inadvertently assist in the undead Queenie’s evil designs via a discussion about how their daughter’s birth was accidental and she was unwanted—Campbell, in direct contrast to many of his horror writer contemporaries, has no problem with flawed protagonists—which Rowan overhears. This only increases the apprehension she feels after Queenie’s death, which allows the latter to manipulate and take control of Rowan’s emotions in the form of Vicky, an unearthly little girl who befriends Rowan, and eventually overtakes her altogether.

A further complaint I’ve heard aired about this book is that it’s sluggishly paced. In comparison to most horror novels it is indeed quite slow, but by 1980s Ramsey Campbell standards it’s positively kinetic, with an orderly and straightforward narrative that may be predictable but still compels, with Campbell’s trademarked hallucinatory descriptions (“The endless dark withdrew into the old eyes, and the room took shape vaguely in the blackness that was only winter gloom after all”) utilized to great effect. No, this is not one of his “best” books, but it is pretty damn good.