Years ago, as a beginner to genre fiction, H.P. Lovecraft’s SUPERNATURAL HORROR IN LITERATURE (1927) came as quite a revelation, with its tantalizing descriptions of countless intriguing-sounding novels and stories with which I was unfamiliar. None was more intriguing to these eyes than William Hope Hodgson’s THE NIGHT LAND, a 1912 novel that Lovecraft praised as “one of the most potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written…there is a sense of cosmic alienage, breathless mystery, and terrified expectancy that is unrivalled in the whole range of literature.” Yet Lovecraft also ascribed a number of shortcomings to the text, including “painful verboseness, repetitiousness (and) artificial and nauseously sticky romantic sentimentality.” Having familiarized myself with THE NIGHT LAND, I can state with certainty that both verdicts are accurate: the novel is indeed a masterpiece, yet it’s also irredeemably flawed, being both the greatest and most problematic work of its brilliant author.

…both the greatest and most problematic work of its brilliant author.

William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918) was a seaman and soldier in addition to one of the world’s most gifted writers of horrific fantasy. His novels include the metaphysical time travel pastiche THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND (1908) and the nautical themed chillers THE BOATS OF THE GLEN CARRIG (1907) and THE GHOST PIRATES (1909), in addition to quite a few similarly minded short stories. THE NIGHT LAND was unquestionably his magnum opus, a massively ambitious 500-plus page epic exploring a theme that was previously breached in THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND: the Earth in its final days, overtaken by a host of otherworldly monsters.

THE NIGHT LAND was unquestionably his magnum opus, a massively ambitious 500-plus page epic exploring a theme that was previously breached in THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND: the Earth in its final days, overtaken by a host of otherworldly monsters.

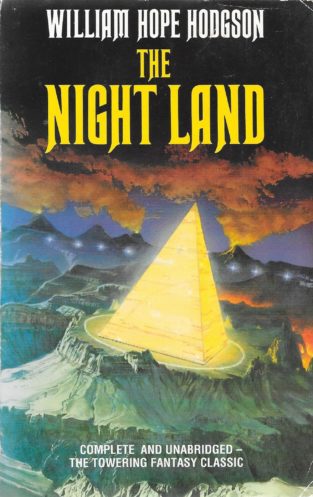

The sun has died in this particular night land, with the remnants of humanity subsiding in a vast pyramid known as the last redoubt, run by an “Earth Current.” Surrounding it are fearsome creatures drawn to the redoubt, according to Hodgson (utilizing his nautical knowledge), like sharks to their prey. Those critters include mutant hounds, bestial men, giant snakes and several imposing “watchers”—mountain-sized monstrosities that do nothing but stare at the pyramid.

The sun has died in this particular night land, with the remnants of humanity subsiding in a vast pyramid known as the last redoubt, run by an “Earth Current.” Surrounding it are fearsome creatures drawn to the redoubt, according to Hodgson (utilizing his nautical knowledge), like sharks to their prey. Those critters include mutant hounds, bestial men, giant snakes and several imposing “watchers”—mountain-sized monstrosities that do nothing but stare at the pyramid.

The main character is a young man residing in the last redoubt who, in a framing device that everyone who’s ever reviewed this book seems to agree is clumsy and ill-conceived, somehow mind-melds with a man living in medieval times. The latter is a heroic knight who, in the interminable opening chapter, courts Mirdath, a young maiden, and then finds himself grief-stricken when his beloved dies.

The opening chapter’s central problem, aside from its overwrought sentimentality, is the near-interminable verbosity of the language, rendered in a deliberately archaic Olde English pastiche that, as once again everyone seems to agree, is excruciating (sample: “And I harked, with strange pain in me, that she did be so in pain; and I ached to bring her ease; yet moved not”). Unfortunately that dialect is continued throughout the remainder of the book, making for a reading experience that’s far from harmonious—although the imaginative richness on display makes an equal impression.

But anyway: the young man in the last redoubt, having mind-melded with the knight, finds himself in telepathic contact with Naani, a young woman residing in a lesser redoubt located a lengthy distance from the other. Naani, it seems, is the reincarnation of the knight’s deceased lover Mirdath, and is threatened by monsters besieging the lesser redoubt. After an attempt by several youths to rescue the lesser redoubt’s inhabitants fails the protagonist elects to set out on his own and find his beloved, armed only with a magic weapon known as a diskos.

There follows the book’s most powerful passage: a novella-length description of the protagonist’s lonely trek through the night land, in which Hodgson’s imaginative power reaches its undoubted apex. The journey is described in minute step-by-step detail, amid a richly detailed, sunless landscape of rocks, fire pits, caverns, slopes and monsters of every conceivable persuasion.

There follows the book’s most powerful passage: a novella-length description of the protagonist’s lonely trek through the night land, in which Hodgson’s imaginative power reaches its undoubted apex.

Eventually the protagonist reaches the lesser redoubt and reunites with his beloved, which occurs around the halfway point. The book’s second half consists largely of the journey back to the last redoubt, which is far less edifying than the previous trek, simply because Naani is along for the ride. This entails some decidedly archaic notions of femininity, with the woman constantly swooning, having to be rescued and getting beaten(!) by her man. That’s in addition to the downright pukeable romantic sap that suffuses this portion of the book, with the protagonist constantly enumerating his love in a succession of horrendously overwrought and repetitive passages (“But the thing that I do have upon my heart doth be that dear and uplifting Power of Love, which I to set forth in this mine own story”) that cripple, though don’t entirely uncut, the proceedings.

What ultimately lingers about THE NIGHT LAND is its mystery and grandeur, both fully sustained throughout its 200,000 word length. As a genre-twisting chunk of imaginative delirium that encompasses science fiction, fantasy and horror—both literal and allegorical—it remains unique.

What ultimately lingers about THE NIGHT LAND is its mystery and grandeur, both fully sustained throughout its 200,000 word length.

Reactions to this masterwork have varied over the years. According to Brian Aldiss it’s “A drama of great and powerful splendor,” while an editorial passage in the anthology HORROR: 100 BEST BOOKS dismisses it as “unreadable.” It would appear to have inspired the cycle of stories that make up Clark Ashton Smith’s “Zothique” universe (collected in the Ballantine paperback of that name) and also Jack Vance’s DYING EARTH series. Interestingly, both Smith and Vance focus on a theme touched upon but not explored by Hodgson: the revival of magic and sorcery in the Earth’s final days. More recent takes on Hodgson’s classic include 2011’s THE NIGHT LAND, A STORY RETOLD by John Stoddard, which purports to retell the story of THE NIGHT LAND in a modern idiom, and 2014’s AWAKE IN THE NIGHT LAND by John C. Wright, a collection of stories set in the world of Hodgson’s novel.

THE NIGHT LAND went through a number of reprintings over the years, most famously as part of the Arkham House omnibus volume THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND AND OTHER NOVELS in 1946 (which needless to say is now a highly expensive collector’s item). Other notable reprintings include the 1990 Grafton mass market edition (one of several Hodgson titles put out by Grafton, all with stirringly lurid cover art) and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series paperback, presented in two volumes and pruned of some of its more sentimental passages. As editor Lin Carter makes clear in his introduction, “in my honest opinion Hodgson is improved by a little pruning.”

THE NIGHT LAND went through a number of reprintings over the years, most famously as part of the Arkham House omnibus volume THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND AND OTHER NOVELS in 1946 (which needless to say is now a highly expensive collector’s item). Other notable reprintings include the 1990 Grafton mass market edition (one of several Hodgson titles put out by Grafton, all with stirringly lurid cover art) and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series paperback, presented in two volumes and pruned of some of its more sentimental passages. As editor Lin Carter makes clear in his introduction, “in my honest opinion Hodgson is improved by a little pruning.”

THE NIGHT LAND went through a number of reprintings over the years, most famously as part of the Arkham House omnibus volume THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND AND OTHER NOVELS in 1946…

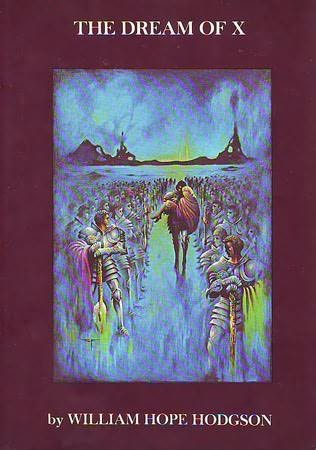

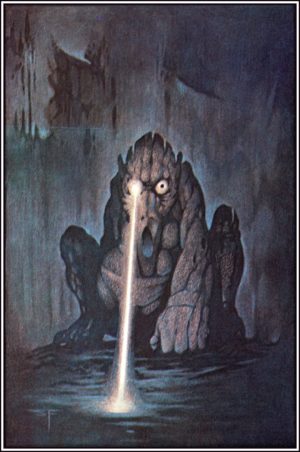

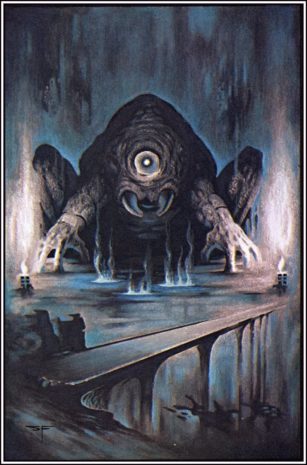

Then there was perhaps the most interesting and vital of all THE NIGHT LAND’S permutations: THE DREAM OF X. This is a severely pared-down (to approximately a tenth of its text) condensation of THE NIGHT LAND, perpetrated by Hodgson himself, that was presented in limited edin hardcover format by Donald M. Grant in 1977. As outlined in the introduction by Hodgson biographer Sam Moskowitz, the initial edition, containing 13 poems and a novelette in addition to the 20,000 word DREAM OF X, appeared in the United States concurrently with the British publication of THE NIGHT LAND in 1912. The Grant edition is worthwhile due to the amazing illustrations by Stephan E. Fabian, particularly those of the Watchers, which succeed in giving eye-popping life to Hodgson’s descriptions.

Then there was perhaps the most interesting and vital of all THE NIGHT LAND’S permutations: THE DREAM OF X. This is a severely pared-down (to approximately a tenth of its text) condensation of THE NIGHT LAND, perpetrated by Hodgson himself, that was presented in limited edin hardcover format by Donald M. Grant in 1977. As outlined in the introduction by Hodgson biographer Sam Moskowitz, the initial edition, containing 13 poems and a novelette in addition to the 20,000 word DREAM OF X, appeared in the United States concurrently with the British publication of THE NIGHT LAND in 1912. The Grant edition is worthwhile due to the amazing illustrations by Stephan E. Fabian, particularly those of the Watchers, which succeed in giving eye-popping life to Hodgson’s descriptions.

Hodgson’s condensation of the text is also impressive. It’s presented as a collection of fragments from a transcription of a dream by “X,” a set-up that is of course nearly identical to that of THE NIGHT LAND, but simplified considerably. Hodgson furthermore managed to include nearly all the highlights of the original narrative—an early description of the night land, the finding of Naani, a climactic fight with the monster hounds—and presented the conclusion virtually intact.

Hodgson’s condensation of the text is also impressive. It’s presented as a collection of fragments from a transcription of a dream by “X,” a set-up that is of course nearly identical to that of THE NIGHT LAND, but simplified considerably. Hodgson furthermore managed to include nearly all the highlights of the original narrative—an early description of the night land, the finding of Naani, a climactic fight with the monster hounds—and presented the conclusion virtually intact.

Ultimately, though, THE DREAM OF X works best as trailer of sorts for THE NIGHT LAND in its complete and unabashed glory. It’s a novel that demands to be read in its entirety (or, in the case of the Ballantine editions, near-entirety), even if doing so is admittedly something of a chore.

Ultimately, though, THE DREAM OF X works best as trailer of sorts for THE NIGHT LAND in its complete and unabashed glory. It’s a novel that demands to be read in its entirety (or, in the case of the Ballantine editions, near-entirety), even if doing so is admittedly something of a chore.