By ANDREW NEIDERMAN (Pocket; 1981)

By ANDREW NEIDERMAN (Pocket; 1981)

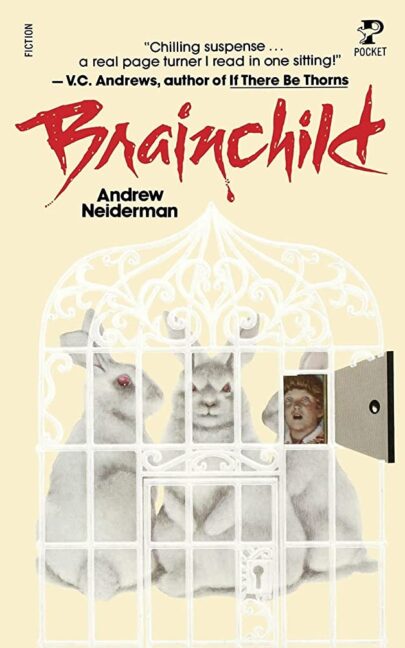

This paperback original was Andrew Neiderman’s follow-up to his 1981 cult novel PIN. Neiderman is best known as V.C. Andrews’ ghostwriter, and PIN, as you may recall, famously referenced Andrews’ FLOWERS IN THE ATTIC with its front cover tagline, “BROTHER, SISTER, MADNESS, SIN, NOW THE TERROR WILL BEGIN,” which could have doubled for FLOWERS. That novel was even more explicitly evoked in BRAINCHILD, which contains an enthusiastic cover blurb by Andrews, and was, as Neiderman has admitted, directly inspired by FLOWERS. Its story of parents locking up their children was inverted in BRAINCHILD, wherein a girl imprisons her parents.

The girl is Lois Wilson, a brilliant science-obsessed teenager. Like many scientists young and old, Lois prizes intellectual curiosity over morality, as reflected in the sadistic experiments she performs on various animals, with her focus being behavioral modification. She also lacks social skills, something that deeply concerns her strict mother Dorothy. Lois’ pharmacist father Gregory tends to be more lenient, although even he can’t help but lament that “his daughter enjoyed working with animals more than she enjoyed working with people.” Lois’ younger brother Billy is another story entirely: he looks up to his sister in borderline worship.

When health problems befall Gregory, who’s prone to debilitating strokes, the family falls apart. Lois, who’s been taking an exclusive behavioral science class with the renowned Professor Kevin McShane, decides to twist the familial trauma to her advantage by turning her parents into test subjects. McShane is an unwitting ally in her scheme, as is Billy, who Lois makes her slave.

…“BROTHER, SISTER, MADNESS, SIN, NOW THE TERROR WILL BEGIN”

A powerful and disturbing premise, related in simple prose that goes by fast–perhaps a bit too fast. The artistry of PIN is nowhere to be found in BRAINCHILD, which bears many signs of the hastiness that would overtake Neiderman’s writing in the years to come. That’s evident in the inconsistent characterizations—Neiderman can’t seem to make up his mind whether Lois is a misunderstood adolescent or a cunning sociopath—and numerous subplots and subsidiary characters that are introduced only to be quickly discarded.

Most pressing of all is the wholly unsatisfying ending, which shuts the madness down just when it’s starting to get going (it’s very much a “That’s IT??” denouement) and caps the book with an on-the-nose moral quandary, voiced by McShane: “You see, despite everything, the scientist in me is still intrigued and wants to be part of this. And you know what, fellow scientists…? That’s what makes it possible for Lois Wilson to exist.” Well said, although it would have been better off not said at all.