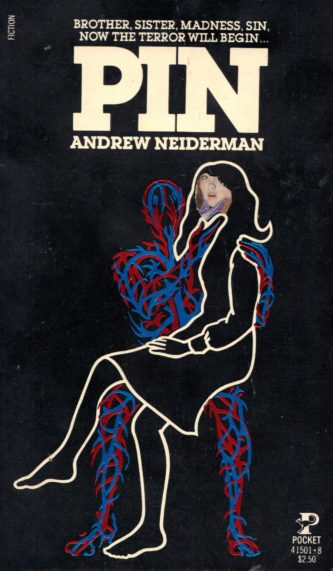

By ANDREW NEIDERMAN (Pocket; 1981)

By ANDREW NEIDERMAN (Pocket; 1981)

Andrew Neiderman, who as of 2010 has published more than 100 novels, can be frustratingly inconsistent, but when he’s “on” he’s hard to beat. PIN, his fourth novel, is such an occasion. Unerringly tight, spare and gripping throughout, I’d say it’s one of the standout horror novels of the 1980s (and was made into a pretty good movie)—and it still holds up.

The set-up is plain nutty, yet Neiderman pulls it off. It’s about Leon and Ursula, a brother and sister who fall under the malevolent spell of a medical dummy they christen Pin (after Pinocchio). The latter is used by their doctor father, who’s obsessed with order and rationality, as a device to bestow the affection on his two children that he’s unable to give, and also deal with their budding sexuality. Unfortunately Pin takes a much greater hold on Leon and Ursula’s imaginations than their father ever anticipated.

Leon is 18 and Ursula 16 when their parents are killed in a car accident. They wind up with their folks’ cavernous house to themselves and Pin, who Leon liberates from his father’s office. Pin’s presence in the house exacerbates Leo and Ursula’s quasi-incestuous union, pushing it to increasingly twisted extremes.

This twisted tale is told from the point of view of the painfully introspective Leon, who’s inherited his father’s clinical manner. He views Pin as a friend and mentor with whom he and Ursula chat regularly–or so it seems. It gradually becomes clear that only Leon is truly under the spell of Pin, with Ursula in thrall to Leon himself, who doesn’t understand the unnatural hold he has on his sister. When she attempts to break that hold by taking up with a guy named Stan, the stage is set for murder.

Some of the developments in the latter half directly recall William Goldman’s MAGIC (novel and film), but otherwise PIN is quite original in conception and execution. The trajectory is uncompromisingly dark and perverse (as evinced by a thoroughly debauched threesome between the protagonists and Pin) and thankfully bereft of the more annoying conventions of eighties’ horror writing (among other things, the book is mercifully free of the expected hypocritical romance). Those attributes extend to Neiderman’s portrayal of his schizophrenic protagonist, one of the most chillingly convincing first person psychopaths I’ve encountered in any novel.