“This film came to our attention, and I said, we’ve got to show this, because it’s surreal, it’s astonishing. It’s sexuality and religiosity and violence and war and love and everything…In the first ten minutes (of the screening) half the audience was gone…Then another bunch would go…Then you would go another fifteen minutes, and then it would reach the next level they couldn’t handle…BOOM! Another fifty are gone…The way they left the theater, women were going up the aisle hitting their husbands, because they had to strike at something. There were men clutching the walls, because their brains had been fried.”

—Harlan Ellison, describing a Writer’s Guild screening of Fernando Arrabal’s VIVA LA MUERTE

The above could only refer to a film by the inimitable Fernando Arrabal, one of the great unrestrained, taboo-bashing visionaries of the cinema. If you’re unfamiliar with Arrabal’s films you’re not alone, as they’ve never attained the popularity of those of Luis Bunuel, Alejandro Jodorowski or David Lynch. The reasons aren’t difficult to fathom: Arrabal’s cinema is dark in every sense of the word, exploring untold depths of torture and corruption born out of his own war-torn upbringing. Even in comparatively lighthearted works like the absurdist J’IRAI COMME UN CHEVAL FOU and the children’s film THE ODYSSEY OF THE PACIFIC, a vivid core of pain and anger is apparent. Furthermore, Arrabal remains a supreme master of shock. Whereas Luis Bunuel in his later years settled into refined surreal comedies like THE DISCREET CHARM OF THE BOURGEOUISE and THAT OBSCURE OBJECT OF DESIRE, Arrabal’s films are very much in the mode of Bunuel’s seminal UN CHIEN ANDALOU, which, you’ll recall, opened with a close up of an eyeball being slashed and continued in that vein, outraging, scandalizing and shocking cineastes the world over.

Like Jodorowski, a longtime colleague who co-founded the infamous Panic Movement of the sixties together with Arrabal and fellow provocateur Roland Topor, Fernando Arrabal is a multi-talented genius conversant in several mediums. While best known as a playwright, with dramas like THE AUTOMOBILE GRAVEYARD and THE ARCHITECT AND THE EMPEROR OF ASSYRIA, Arrabal is also an artist, poet and author of many classic works of fiction, in particular THE BURIAL OF THE SARDINE, THE TOWER STRUCK BY LIGHTNING and THE COMPASS STONE. Alas, his career as a filmmaker has proven deeply erratic; again like Jodorowski, Arrabal the moviemaker thrived in the early seventies, with VIVA LA MUERTE and J’IRAI COMME UN CHEVAL FOU, bonafide masterworks of surrealism, but his cinematic output tapered off over the next decade, stymied, perhaps, by the realities of an increasingly restrictive industry.

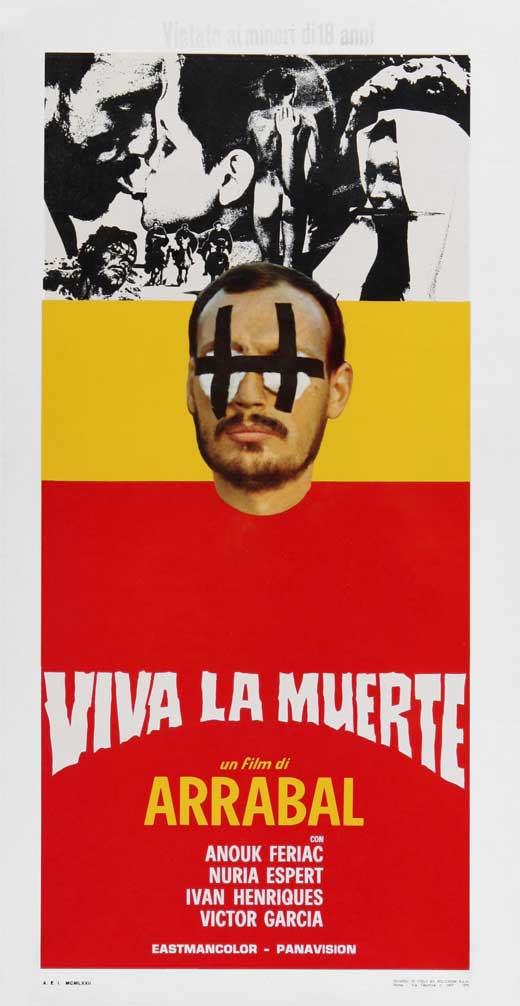

VIVA LA MUERTE was Arrabal’s debut feature, and remains his most fully realized masterpiece, a confounding blast of cinemadness that burst upon the world in 1971 (alongside equally mind-rattling masterworks like THE DEVILS, PERFORMANCE, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE and EL TOPO). It was adapted from his 1959 novel BAAL BABYLON, which in lieu of a conventional narrative contained a series of incidents recalled by an unnamed narrator about his Civil War-set childhood, in the form of notes to his mother. She was an ignorant and self-righteous woman forever trying to justify the fact that she turned her husband in to fascist authorities years earlier; the boy (named Fando in the film) nevertheless harbors incestuous longings for her. He takes to obsessively smoking a pipe that once belonged to his father, a “Doctor Plumb” pipe. He’s also molested by his perverted Aunt Clara, who likes to have him beat her with a strap, and manhandled by his grandmother, who labors under the misapprehension that he’s a girl, because, as he recalls, “I put it on the right when I should have put it on the left, the way all men do.”

VIVA LA MUERTE, 1971 (Trailer)

The autobiographical elements in the book and film are undeniable: Arrabal was born in Span in 1932 and raised during the Spanish Civil War. His father was a Spanish officer branded a traitor and imprisoned by the military; he escaped in 1942 and was never heard from again. Arrabal relocated to Paris in 1955, a voluntary exile from his homeland because, “In Spain, everyone suffocates. I do not like to play the part of victim.”

His Spanish upbringing looms large in Arrabal’s work, although nowhere larger than in BAAL BABYLON and VIVA LA MUERTE (Arrabal’s early one-act melodrama THE TWO EXECUTIONERS is also worth mentioning, being the stark account of a woman who has her husband thrown in jail and then desperately tries to justify her actions to her two sons, disappearing offstage at one point to rub salt into her tortured beau’s wounds). The two make for a fascinating comparison, being literally two sides of the same coin. VIVA LA MUERTE was adapted from BAAL BABYLON, but tonally the former is diametrically opposed to the latter, a spare, muted account that relies on suggestion and repetition to achieve its effects. The film, on the other hand, is an assaultive affair that revels in violence and perversion. One could argue Arrabal was cheapening his work with gratuitous exploitation if not for that fact that his art in general was moving in that direction (contrast his 1958 play THE AUTOMOBILE GRAVEYARD, considered shocking in its day because it contained offstage beatings and urination, with his 1973 drama AND THEY PUT HANDCUFFS ON THE FLOWERS, which featured onstage fellatio and defecation). It seems that in BAAL BABYLON Arrabal was testing the waters in which he would fully immerse himself in VIVA LA MUERTE.

It may have been Arrabal’s first feature, but VIVA LA MUERTE demonstrates an assurance that belies its creator’s amateur status. Arrabal isn’t afraid to challenge long held cinematic conventions in the flood of hallucinations that engulf the film at the rate of one every few minutes, conveying its central character’s disturbed inner state via incestuous sadomasochistic fantasies featuring his mother torturing his incarcerated father in some grotesque manner (gouging his eyeballs, defecating on his head, etc.). Said fantasies were shot on video and then transferred to film after being processed through various colored filters, a revolutionary process back in 1971. Equally innovative is the soundtrack, a blare of Spanish folk tunes, commercial jingles and, most effectively, a Dutch children’s song played over the opening credits (which also feature macabre drawings by fellow Panic Movement founder Roland Topor) that assumes truly horrific stature when contrasted with the film’s depiction of the death—or murder—of childhood innocence.

Arrabal brought out the best in his collaborators on VIVA LA MUERTE. Cinematographer Jean-Marc Ripert (who also photographed Claude Faraldo’s infamous THEMROC) creates unforgettable sun baked imagery, conjuring forbidding subconscious mindscapes out of rocks, cliffs and deserted battlements. The acting is uniformly exceptional, particularly that of Mahdi Chaouch as Fando, certainly one of the most impressive child performances I’ve encountered in any film, and the statuesque Nuria Espert as his mother, who conveys a disturbing aura of menace and seduction.

Unsurprisingly, the film encountered censorship problems in its native France, where it was withheld from distribution for over a year. Also unsurprising was the furor that occurred during its initial release, with Espert claiming she was blacklisted for a year following MUERTE’S completion. The film was especially controversial in America (see the above Harlan Ellison quote), where it played the New York midnight movie circuit for ten weeks straight.

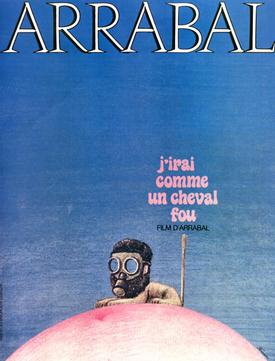

Arrabal followed VIVA LA MUERTE with the equally subversive J’IRAI COMME UN CHEVAL FOU. The title is a phrase that recurs throughout Arrabal’s work, and can be translated several ways: “I will go like a runaway horse” or (as it appears in the English text of Arrabal’s play AND THEY PUT HANDCUFFS ON THE FLOWERS) “I’ll go like a rogue stallion.” The Cult Epics DVD release translates it as I WILL WALK LIKE A CRAZY HORSE (it’s available as part of a set that includes MUERTE and THE GUERNICA TREE).

J’IRAI COMME UN CHEVAL FOU (Trailer)

J’IRAI…, in direct contrast to the previous film, is a raucous and satirical affair, though every bit as political. Its targets include industrialization, organized religion, institutionalized violence, meat eating and gender roles (complete with a “woman” who makes a shocking reveal in a scene nearly identical to the one that would cement THE CRYING GAME’S fame twenty years later)—in short, the entire Western world. With J’IRAI…, Arrabal was seeking to strip the façade of “civilized” behavior and reveal the primitive urges and brute force lurking underneath.

The film features another castrating—an adjective presented in extremely literal fashion—mother figure, who the protagonist Aden, a straight-laced businessman haunted by memories of his abusive childhood, kills in the opening minutes. This precipitates a desperate flight into the desert where he meets Marvel, a sand eating dwarf who communicates with animals and can change day to night with a snap of a finger. The two quickly become inseparable (we know they’ve got a special bond because they have a back-to-back shit in the sand), and Aden takes Marvel back to civilization for an odyssey of alienation and disillusionment. Marvel briefly joins a circus, in the process loosing a lion upon a cheering crowd, while Aden goes back to his mother’s mansion, dresses in her lingerie and gives birth to a human skull.

The surreal intercuts of VIVA LA MUERTE are back, with a plethora of unforgettably grotesque images, including skeletons hanging from streetlights, a tongue nailed to a board, a gas mask wearing couple having sex, a kid menaced by a giant spider, the heroes trapped in a large transparent ball rolled around by outraged churchgoers, etc. There’s also a multi-layered soundtrack similar to that of the earlier film, complete with another portion of the children’s song that graced MUERTE. American actor George Shannon acquits himself well as Aden, while the diminutive, bushy bearded Hashimi Marhcuk makes for an unforgettable sight as Marvel (Arrabal claims Marchuk was cast because “he was my double on Earth”).

Like its predecessor, J’IRAI… was quite controversial. It was banned for over a year by the French government, and went unreleased in the US until the appearance of the Cult Epics DVD.

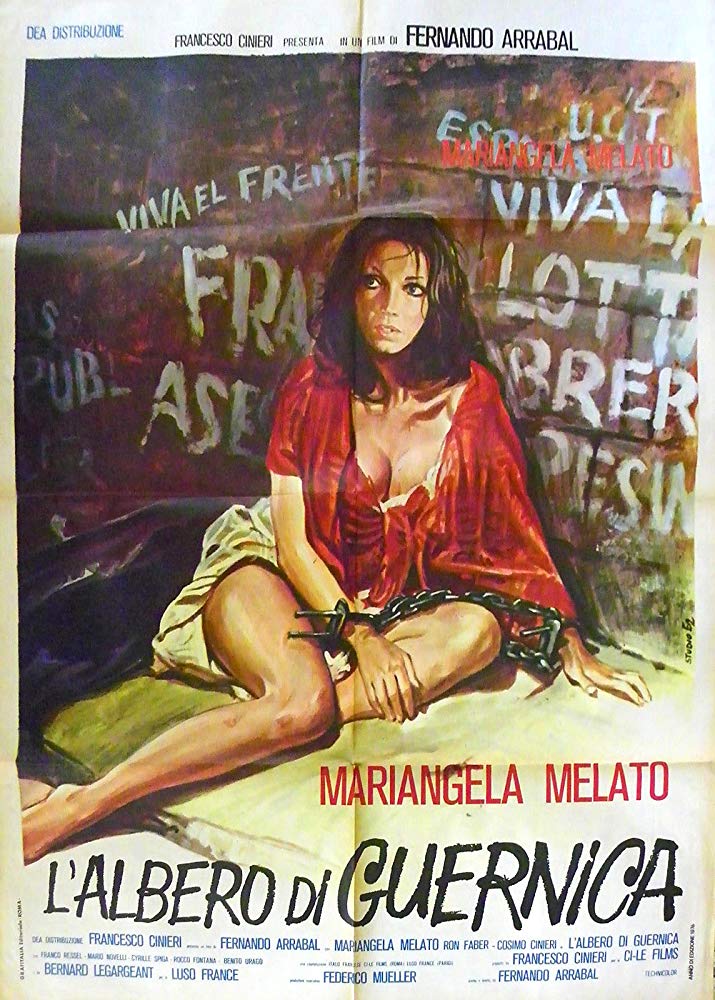

Arrabal’s next film was the French-Italian co-production L’ARBRE DE GUERNICA in 1975. After his previous forays into the medium it seemed Arrabal could do no wrong as a filmmaker—GUERNICA, however, was a big step down. It attempts to depict the Spanish Civil War that figured in VIVA LA MEURTE in a more panoramic fashion, via the fictional Spanish village of Villa Romero, whose citizens find themselves under siege when they elect to oppose Generalissimo Franco’s regime. While it has its strong points, GUERNICA ultimately falls into the Interesting Failure category, being a scattershot affair that attempts to fit the surreal grotesquerie of the earlier films into a more audience friendly narrative. The combination is an uneasy one, with bizarre images (a naked child seated atop a mound of skulls, a matador impaling an immobilized dwarf) alternating with commercial sentimentality so shameless it wouldn’t feel out of place in a Bollywood movie.

And the film’s problems don’t end there, as it has many flaws common to expensive European movies of the seventies: the battle scenes are draggy and overlong (in an apparent attempt at justifying all the money spent on them), the accents and acting styles are always clashing, the characters tend to speak in political slogans rather than actual dialogue, and furthermore there are just too many of them. The last point is a particularly sore one, as there are at least half a dozen central characters who all-but crowd out the star-crossed love story at the film’s center, and nor does it help matters that the lovers, a witch woman (played by Italian starlet Mariangela Melato, best known for her role in the original SWEPT AWAY) and a surrealist artist, only get together twice in the entire film.

SWEPT AWAY 1974 (Trailer)

GUERNICA, despite its expensive pedigree, received even less commercial exposure than J’IRAI…, and all-but vanished from circulation until the 2005 DVD release. Arrabal didn’t make another film until 1981, that film being the French-Canadian production THE ODYSSEY OF THE PACIFIC (a.k.a. THE EMPEROR OF PERU), surely one of his oddest concoctions. A children’s film with all the trimmings—cloying cutesiness, underage mugging, music numbers and Mickey Rooney—it is nonetheless an intriguing work with at least one stand-out scene.

One of the three child protagonists of THE ODYSSEY OF THE PACIFIC is a Cambodian refugee suffering horrific memories of his exiled father, who was apprehended by authorities and shipped off to a prison camp. Thus the kid is something of a cousin to VIVA LA MUERTE’S Fando, and indeed THE ODYSSEY OF THE PACIFIC as a whole can be viewed as a G-rated redo of the earlier film. Once again the narrative is frequently interrupted by surreal reveries, although not on the same level as those of MUERTE. The torture and defecation of the earlier film have given way to sanitized wish fulfillment fantasies in which a boy drives a race car, conducts a symphony and performs in a circus.

THE ODYSSEY OF THE PACIFIC, AKA The Emperor of Peru, 1981 (Trailer)

Mickey Rooney plays a nut who identifies himself as The Emperor of Peru, and inspires the three tykes to fix up an old locomotive and use to it transport the refugee back to Cambodia so he can marry his mother (the hints at incest are, I’m guessing, not entirely unintentional). This leads to an exhilarating finale that’s easily the highlight of the film, in which the kids succeed in charging up the locomotive and chug off into the sunset.

Arrabal’s next cinematic foray was LE CIMITIERE DES VOITURES (THE AUTOMOBILE CEMETARY), based on his famous 1958 play. The film is a colorful lark set in a post-apocalyptic world where various people eek out a living in an automobile graveyard, bickering, screwing and, this being an Arrabal production, getting constantly harassed by corrupt authority figures. Among the patrons of the automobile cemetery is none other than Jesus Christ, here incarnated as a rock guitarist wanted by the authorities.

The Christ figure was a jazz musician in the play, and that’s certainly not the only change Arrabal wreaked upon it. As he did in adapting BAAL BABYLON, Arrabal broadened the material considerably, from a modest two act drama into a veritable epic, with the surreal-grotesque quotient multiplied exponentially. Whereas the play had a total of seven characters, the film contains at least a dozen, not to mention countless extras milling about in the background of each scene, among them angels, flagellants, tightrope walkers, mermaids and punk rockers in what I assume was intended as a cross section of early eighties society.

Unfortunately, unlike in VIVA LA MUERTE, the broadening process hasn’t improved the material much—in fact I’d say it’s lessened it considerably. A large part of the play’s charm was the tension between what occurred onstage and what we couldn’t see, which included urinating and screwing inside cars, people being tortured in the wings, etc. Here everything is made visible to us, which, combined with the unvarying one-note tone and relentlessly episodic narrative, quickly grows dull. The hopelessly outdated fashions and music are further liabilities. This isn’t to say that the film doesn’t have its moments—it does, particularly in the sight of the Christ figure in a pool race, walking atop the water in which his competitors swim—just that it falls far short of its potential.

Arrabal would make two more films, bringing the total to seven. (Arrabal: “I am like God…after the seventh film, I rested.”). I’m probably remiss in calling ADIEU, BABYLONE! (FAREWELL BABYLON) and JORGE LUIS BORGES: UNA VITA DE POESIA (JORGE LUIS BORGES: A LIFE OF POETRY) “films,” as both are hour long made-for-French-TV reveries. ADIEU, BABYLONE!, released in 1992, was based on Arrabal’s novel of the same name about a poetically inclined murderess tormented by horrific childhood memories. Arrabal “adapts” this tale by having the novel’s text recited by an unseen narrator over video footage of actress Lelia Fischer wandering through New York City and interacting with homeless people, street protesters and a few famous folk (notably Spike lee and Melvin Van Peebles). She also does odd things like lie down in the middle of a sidewalk and smooch a fish, all in full view of appalled onlookers. The most striking scenes are the frequent VIVA LA MUERTE snippets that are used to illustrate the horrors of the protagonist’s childhood. Otherwise, though, ADIEU, BABYLONE! is probably most interesting as a documentary snapshot of New York City in the early 1990s.

1998’s JORGE LUIS BORGES: UNA VITA DE POESIA consists of the legendary Argentine scribe Jorge Luis Borges giving the final interview before his death in June 1986. Borges was unquestionably one of the world’s great thinkers, and his commentary, touching on poetry, literature, dreams and death, is interesting enough to make for a worthwhile viewing experience. In an apparent attempt at delineating the similarities between Borges’ art and his own, Arrabal intercuts snippets from his films, and scores it all with the French childrens’ tune that was so memorably inverted in VIVA LA MUERTE. Also included are details from various works of art and staged scenes involving a shirtless young boy and an old man (which I’m guessing are meant to represent Borges at different stages of his life).

Thus, discounting Arrabal’s acting roles in films like Jacques Baratier’s PIEGE (1968), William Klein’s WHO ARE YOU, POLLY MAGOO? (1966) and Peter Fleischmann’s THE HAMBURG SYNDROME (1979), and his many plays adapted for European television (all currently unavailable for screening), we’re finished with Fernando Arrabal’s cinematic output. However, there are two more films that need to be covered, as both were adapted from Arrabal’s work by other directors.

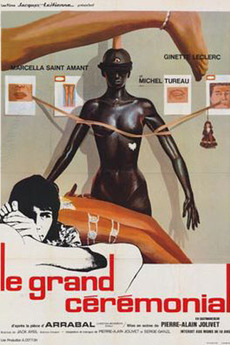

First in this category is LE GRAND CEREMONIAL (1967), from the French counterculture filmmaker Jean-Pierre Jolivet. It’s a noisy, raucous affair, adapted from what has been called “Arrabal’s weirdest play yet.” That, my friends, is no small claim! The play might be a complex allegorical portrait of male-female relations or possibly just a sustained bad joke—or maybe it’s simply complete nonsense. What I can say with certainty is that the PC crowd would doubtless be up in arms over its decidedly non-feminist portrayal of the fairer sex (“Let me lie here at your feet like a dog”, a woman begs her lover at one point), and the less-than-respectful manner in which the male protagonist treats his beloved (in one of his more romantic moments he tells her: “Your back is lily-white for me to scourge, your voice is full of sorrow for your death”).

Jolivet adapts LE GRAND CEREMONIAL with all the pomp he can muster, including a bombastic music score played at full volume throughout and insanely kitschy art direction that makes the late sixties décor of A CLOCKWORK ORANGE look restrained. The central character is Cavanosa, a young man emotionally crippled by his overbearing mother. Unable to relate to flesh and blood women, he lavishes affection on mannequins…but when the living, breathing Sil, an unrepentant masochist, enters the picture, Cavanosa finds a willing receptacle for his pent-up frustrations. It quickly becomes apparent that Sil is his ideal woman: she begs him to whip her, and nor does she mind when he places a crown of thorns on her head and tries to strangle her to death. This is all pleasing enough for Arrabal fanatics like myself, but Jolivet’s love-conquers-all ending is a sore spot, ignoring as it does the ironic finale of the play, in which Cavanosa is approached by another masochistic woman who adds a dimension totally absent from this crazed yet fatally conservative film.

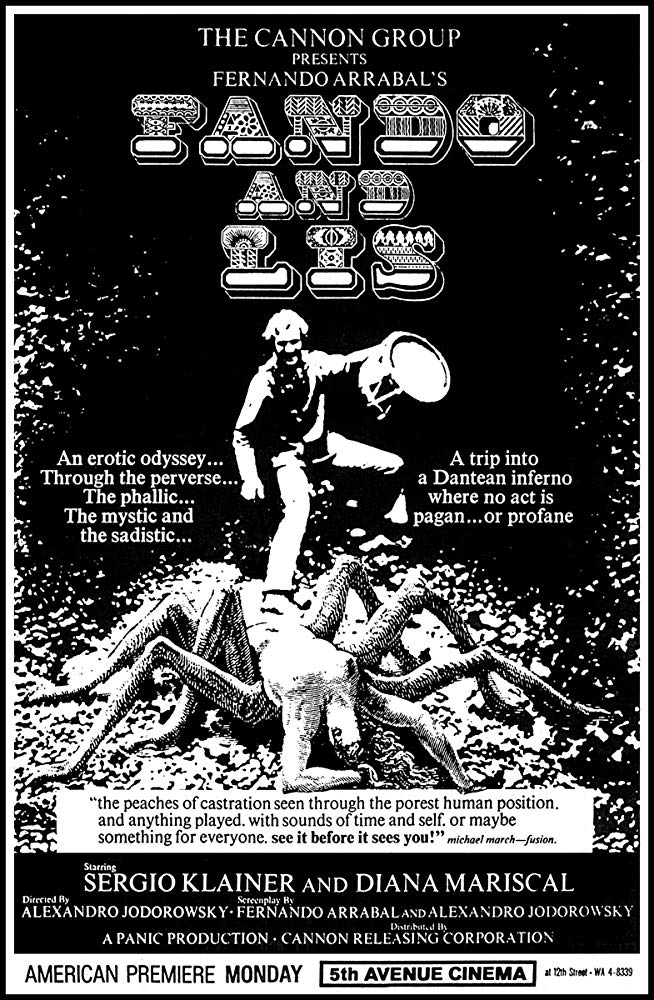

Alejandro Jodorowski’s black and white FANDO Y LIS (1968) is far wilder. It was adapted from Arrabal’s modest play of the same name (which Arrabal calls “a total mystery to me”), but in extremely loose fashion: filming in Mexico on a decidedly limited budget, Jodorowski worked entirely from a one-page script. It centers on Fando, a blonde young man, and Lis, his crippled girlfriend, who Fando wheels in a stroller over a rocky, mountainous landscape in search of the fabled city of Tar. Fando and Lis never reach their destination, waylaid as they are by assorted weirdoes of every imaginable variety; eventually Fando, in a fit of frustration, kicks Lis to death.

Jodorowski, whose first film this was, definitely made the material his own, tossing in all manner of symbolic insanity of a type familiar to viewers of his later films EL TOPO and THE HOLY MOUNTAIN. A man drinks blood onscreen, another plays a burning piano, piglets erupt from a woman’s vagina, men break eggs over the head of a little girl, the hero is pelted with bowling balls, an orgy is performed in a mud pit, a tarantula is burned alive, etc. FANDO Y LIS is certainly not without interest, but it’s so undisciplined and excessive that the central characters are frequently overshadowed, and the whole thing ultimately grows tiresome.

The film apparently caused a mini-riot during its premiere screening at the 1968 Acapulco Film Festival and was banned in Mexico shortly thereafter. It’s said to have “changed the face of Mexican cinema” forever, and if nothing else marked the introduction of a number of future talents, as Arrabal, Jodorowski, producer Juan Lopez Moctezuma and cinematographer Rafael Corkidi all went on to auspicious directorial careers.

LE GRAND CEREMONIAL and FANDO Y LIS are first and foremost products of their time, as, it could be argued, are all Arrabal’s films. Could VIVA LA MUERTE or J’IRAI COMME UN CHEVAL FOU be made today, anywhere in the world? Highly doubtful in both cases, as both were part and parcel of an era when similarly freewheeling talents like Jodorowski, Jolivet, Carmelo Bene, Donald Cammell, Andrzej Zulawski, William Klein and Peter Watkins flourished, creating bold and unfettered cinematic landmarks that remain unsurpassed. How many of those men, delirious geniuses all, are still making movies today? Answer: none.

However, there is a bright note. Arrabal and his contemporaries may no longer be making films, but their influence is evident in the work of modern talents like Clive Barker (a longtime champion of VIVA LA MUERTE), Takashi Miike, Guy Maddin, Shinya Tsukamoto, Gaspar Noe, Jan Kounen, Alex Cox, Crispin Glover, and Nicolas Winding Refn. True genius never truly dies, and neither, I’m certain, will Fernando Arrabal’s cinematic legacy.