Grant Morrison is one of most intelligent, unpredictable and plain nutty comic book scripters in existence. His 1989-93 writing for DOOM PATROL is not his best work, but it is certainly among his most representative.

Grant Morrison is one of most intelligent, unpredictable and plain nutty comic book scripters in existence. His 1989-93 writing for DOOM PATROL is not his best work, but it is certainly among his most representative.

The reviews, as always with Morrison, were mixed (The Comics Journal dubbed it a “big empty nothing”), but Morrison’s work on DOOM PATROL, with illustrations provided (mostly) by Richard Case, has become somewhat iconic. DC’s Vertigo imprint wasn’t yet a thing when Morrison got going on the series, which directly foreshadowed many Vertigo titles, as well as the similarly conceived XOMBI (whose creator John Rozum took what seemed like a swipe at Morrison in his claim that “This series is not structured as XOMBI vs. surreal monster of the month,” which DOOM PATROL apparently was). For comic readers in the late eighties and early nineties it served as, simply, an excellent introduction to the talents of Grant Morrison, and a barometer of how weird comics back then could possibly get.

DOOM PATROL, whose heroes were touted as the “world’s strangest,” was spun off from the DC saga MY GREATEST ADVENTURE in June 1963. Not one of DC’s more popular titles, it’s most famous, arguably, for having allegedly been regurgitated by Marvel as X-MEN (so claimed DOOM PATROL’S creator Arnold Drake), which debuted a few months later and, like DOOM PATROL, was comprised of a band of misfits led by a physically incapacitated old guy.

DOOM PATROL in its initial form was cancelled in 1968, and followed by scattered appearances by its principals in various DC comics and anthologies prior to an official resurrection (the first of many) in 1987. Written by Paul Kupperberg and drawn by Steve Lightle and Erik Larsen, this new incarnation was, in light of the “strangest superheroes” claim, disappointingly conventional in its approach. Enter Scotland’s Grant Morrison.

principals in various DC comics and anthologies prior to an official resurrection (the first of many) in 1987. Written by Paul Kupperberg and drawn by Steve Lightle and Erik Larsen, this new incarnation was, in light of the “strangest superheroes” claim, disappointingly conventional in its approach. Enter Scotland’s Grant Morrison.

In 1989 Morrison was known for an approach that was decidedly unorthodox. Having begun writing for comics at age 17, by ‘89 Morrison was already semi-famous for THE LIBERATORS and 2000 AD’s ZENITH. Another auspicious credit was the revivification of DC’s ANIMAL MAN starting in 1988, with Morrison asked to do the same for DOOM PATROL the following year—in which Morrison would cause further trouble with the bestselling (and oft-censored) graphic novel ARKHAM ASYLUM and the Cut magazine published, Steve Yeowell illustrated serial THE NEW ADVENTURES OF HITLER.

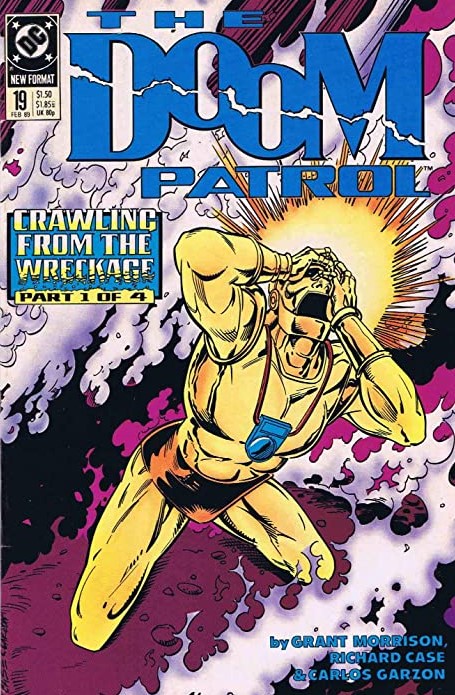

Morrison’s run on DOOM PATROL started on issue #19, with the four part “Crawling from the Wreckage.” In it Morrison carried forward with a few of the Patrol’s initial members, such as its wheelchair bound chief Dr. Niles Caulder (whose motives are revealed to be somewhat less than pure) and the “Robotman” Cliff Steele (the “man” part of whose name, we eventually learn, is inaccurate), with Paul Kupperberg having obligingly killed off those characters whose arcs Morrison didn’t want to continue.

We’re also introduced to several new, Morrison invented Doom Patrollers. They include Crazy Jane, a cute brunette harboring multiple personalities, one of which turns her into a ravenous slut named Scarlet Harlot (here, as in much of the rest of the comic, political correctness is thrown to the wind); a sentient inter-dimensional city block known as Danny the Street that communicates via flashing signs and self-typing typewriters (and whose true origins aren’t revealed until issue #62); Rebis, a multi-gender entity created from the merging of several original DOOM PATROL characters; and the Charles Atlas inspired Flex Mentallo, whose origin was explored in issue #42, and who later headlined a Morrison scripted miniseries (more on that in a bit). Morrison also elevated to protagonist status a minor character from past issues, the ape-faced Dorothy Spinner, who has the ability to conjure up imaginary beings.

Then there are the Scissormen. Inspired by the thumb slicing scissor man from STRUWELPPETER, these interdimensional freaks, the chief antagonists of “Crawling from the Wreckage,” have the power to literally separate a person from his or her present reality via malevolent scissor hands. The Scissormen speak in nonsense phrases (“Thirdly be grimmer as fond brevities”) redolent of the “cut up” writing method utilized by William Burroughs and Bryon Gysin (and directly inspired, reportedly, by the spell check feature on Morrison’s word processor), and rule over an interdimensional city known as Orqwith.

Then there are the Scissormen. Inspired by the thumb slicing scissor man from STRUWELPPETER, these interdimensional freaks, the chief antagonists of “Crawling from the Wreckage,” have the power to literally separate a person from his or her present reality via malevolent scissor hands. The Scissormen speak in nonsense phrases (“Thirdly be grimmer as fond brevities”) redolent of the “cut up” writing method utilized by William Burroughs and Bryon Gysin (and directly inspired, reportedly, by the spell check feature on Morrison’s word processor), and rule over an interdimensional city known as Orqwith.

Other villains include the Candleman, a malevolent projection of Dorothy’s subconscious; the Keysmiths, Crazy Jane-created personages who seek to unlock everything because “They think every question has an answer and they won’t rest until there are no questions left”; John Dandy, a deranged government operative with scrabble pieces in place of eyes and several bodiless heads orbiting his own; Shadowy Mr. Evans, the latest incarnation of the serpent from the Garden of Eden, who seeks to liberate mankind’s darkest perversions; the Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E., “normalcy agents” seeking “to eradicate eccentricities, anomalies, and peculiarities wherever we find them”; and a lovingly detailed coalition known as the Brotherhood of Dada, led by Mr. Nobody, a.k.a. “the Abstract Man.”

This concentration on colorful villains points up the series’ most pressing problem: the fact that Morrison is clearly more interested in the bad guys than the good ones. Mr. Nobody and the Brotherhood of Dada in particular seem to fascinate Morrison, with they getting a great deal more face-time than the Doom Patrol in issues 49 (in which a whole new BoD is introduced) through 52. Certainly Mr. Nobody’s determination to “declare war on the way things are” would seem to resonate with the famously anarchistic Morrison, as would Mr. Evans’s issue #48 rant about “this sad tableau of ordinary life” in which people are “crushed by repression, unable to express their true desires.”

Another very Grant Morrison-centric problem is that such a mélange of weirdness-for-weirdness’ sake can become exasperating. I’m not sure precisely what-all happens in the unfocused “Aftermath” (issue #46) and, more pressingly, I’m finding I don’t much care. And then there’s Morrison’s (intentionally?) naïve depiction of the Doom Patrol’s native America, as evinced by the oft-asked question “Why does the Pentagon have five sides?” Answer: because it represents the five branches of the US military, although Morrison reasons that the five sides are due to occult machinations.

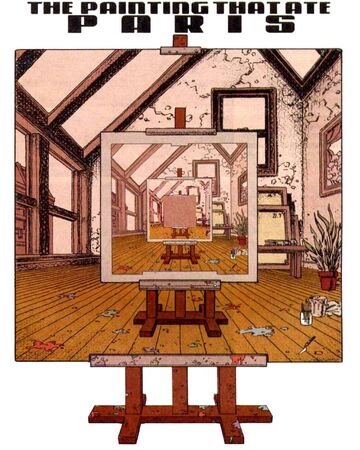

Yet the warped imagination that suffuses this DOOM PATROL is unprecedented. It’s very much on display in “The Painting that Ate Paris,” introduced in issue #26, a multi-layered abstract painting that, as its moniker suggests, can devour reality. There’s also a magic bus manned by Mr. Nobody that debuts in issue #50, in which the Psychedelic Era of the late 1960s, whose imagery and worldview inform so much of Morrison’s oeuvre, is made explicit; it’s also in issue #50 that Mr. Nobody announces a run for president. Wordage like “I’ve had enough of your pathetic sepulchral voice and your shitty death rays” could only spring from the mind of Grant Morrison, whose knowledge of all things weird is evinced in references to the ANYHOW STORIES of Lucy Clifford, the writings of Thomas de Quincey, THE PRISONER and figures like John Parsons, Albert Hofmann and Ferdinand Cheval.

The series has been said to tend “towards comedy rather than the traditional melodrama of American comic books,” and Morrison isn’t above some grade school-level humor. An example would be when the Patrol goes up against an anti-beard crusader who seeks to cut off Caulder’s facial hair. Philip K. Dickian reality displacement is another constant (although Morrison claims not to have read much of Dick’s writing), and nor is Morrison averse to perverse sexuality, as in issue #48, when Shadowy Mr. Evans presides over a vast erotic dream that spills over into reality. Here, though, the somewhat less-than-invigorating, overly conservative artwork of Richard Case lets the comic down.

Mr. Case (who got occasional help from Philip Bond and Ken Steacy) contributed artwork that is strong—above average, even—but not exceptional. Morrison needs an artist on the level of Dave McKean (of ARKHAM ASYLUM) or Duncan Fegredo (who did the honors on the Morrison scripted KID ETERNITY) to do his imaginings justice; Richard Case is talented enough to conceivably fit the bill, but the accelerated time frame of a monthly comic doesn’t leave a lot of room for artistic nuance. Case’s visualization, for example, of “the Ant Farm,” a horrific enclosure beneath the Pentagon whose mere sight can supposedly drive men insane, is a major let-down.

Mr. Case (who got occasional help from Philip Bond and Ken Steacy) contributed artwork that is strong—above average, even—but not exceptional. Morrison needs an artist on the level of Dave McKean (of ARKHAM ASYLUM) or Duncan Fegredo (who did the honors on the Morrison scripted KID ETERNITY) to do his imaginings justice; Richard Case is talented enough to conceivably fit the bill, but the accelerated time frame of a monthly comic doesn’t leave a lot of room for artistic nuance. Case’s visualization, for example, of “the Ant Farm,” a horrific enclosure beneath the Pentagon whose mere sight can supposedly drive men insane, is a major let-down.

As it happened, Morrison’s DOOM PATROL scripting concluded with issue #63 (while Case stayed on through #66), after which the series was given the Vertigo imprint and Rachel Pollack took over scripting duties (a job, rumor has it, she got by begging for it in missives published in the “Letters to the editor” section). Pollack’s DOOM PATROL issues that I’ve read aren’t bad, but they’re not Morrison level, which explains why DOOM PATROL folded in April 1995. It was resurrected a third time, with John Arcudi as writer, in 2001, followed by a John Byrne scripted 2004 incarnation, a 2009 one by Keith Giffen and a 2016 one by Gerard Way. Topping things off was the DCU’s DOOM PATROL TV series, starring Timothy Hutton and Brendan Fraser, which debuted in 2019 and has lasted three seasons.

Grant Morrison kept busy in the years since leaving DOOM PATROL, providing the scripts for several more comic series. The most notable was THE INVISIBLES, a self-created Morrison scripted series that ran from 1994 to 2000. Widely believed to have exerted an uncredited influence on THE MATRIX, THE INVISIBLES was much stranger, and far more personal, than the Morrison DOOM PATROL, although it bore many of the same problems afflicting the former series.

Another noteworthy Morrison project was FLEX MENTALLO, a four issue miniseries about a character introduced in the pages of DOOM PATROL, that was gorgeously illustrated by Frank Quitely (who collaborated with Morrison again on 2005’s WE3). Flex is a muscle-head who can alter reality by twitching his muscles (which in DOOM PATROL resulted in the Pentagon briefly becoming a circle), although there’s shockingly little of that in this series. It focuses mostly on Flex’s creator, a suicidal runt named Wally Sage whose creations are spilling out into the real world, and in some cases retreating back into the comics-verse. The ever-shifting boundary between differing layers of reality (several of which are juxtaposed here) and imagination is the true theme of this complex, confounding and often downright obnoxious miniseries, which came under fire when the Charles Atlas Company filed a copyright infringement suit against DC Comics. The suit was quickly dismissed, but it resulted in the series going uncollected until 2012, when a deluxe hardcover edition of DOOM PATROL was released.

I’ve heard tell that more Flex Mentallo adventures were intended, but as of 2021 they have yet to appear. Thus Grant Morrison’s tenure on DOOM PATROL can said to be concluded, meaning any interest I might have in the series, or its TV spin-off (below) is likewise finished. RIP.