By GRANT MORRISON, STEVE YEOWELL (Crisis #46-49; 1989/90)

By GRANT MORRISON, STEVE YEOWELL (Crisis #46-49; 1989/90)

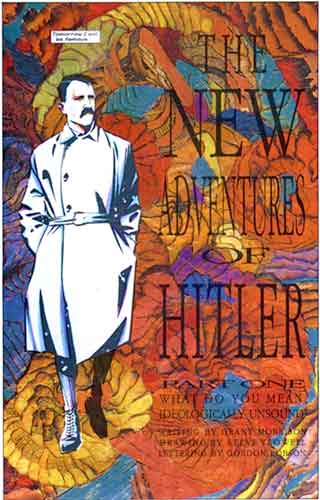

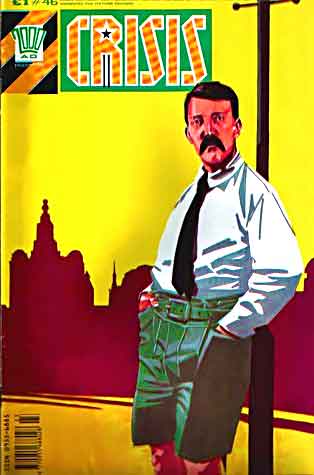

Here was have what is probably the most controversial work in a career that has seen no shortage on controversy. THE NEW ADVENTURES OF HITLER was a Grant Morrison scripted comic strip that debuted in the Scottish arts magazine Cut in 1989, and caused a furor that resulted in one of Cut‘s editors, singer/political activist Pat Kane, quitting in protest. The series was reprinted in 1990, in the 2000 AD spinoff mag Crisis, and the outrage apparently continued unabated (much to the delight of Morrison, who’s since proclaimed that “I liked courting controversy–more flames to the fire!”). As of 2017 the series has yet to be released in standalone comic book/graphic novel format, and probably won’t anytime soon.

In truth, as with most contested literature, THE NEW ADVENTURES OF HITLER, isn’t nearly as shocking or outrageous as expected. As is usually always true in such cases, there’s a high probability that the finger-pointers didn’t bother to actually read the strip before condemning it.

Running a total of 48 pages, THE NEW ADVENTURES OF HITLER exists only in a “Part One,” subtitled “What Do You Mean, Ideologically Unsound?” It seems there was once a part two in the works that never came to fruition; no matter, as “What Do You Mean, Ideologically Unsound?” is cohesive enough, with a beginning, middle and satisfying end. The tone, as is evident in the subtitle, is satiric, though never especially broad or distractingly so.

Morrison’s aims, in fact, are very much in keeping with those of subsequent novels and films that offer fictional depictions of Adolf Hitler’s early years (including the 2014 novel HUNTERS IN THE SNOW by D.M. Thomas and the 2003 film MAX). For that matter, THE NEW ADVENTURES OF HITLER’s main narrative hook was one that had already been utilized by the British novelist Beryl Bainbridge (in 1978’s YOUNG ADOLPH): an alleged 1912-13 sojourn in Liverpool by a young Adolph Hitler, as was claimed (falsely) by Hilter’s sister-in-law Bridget.

Morrison’s aims, in fact, are very much in keeping with those of subsequent novels and films that offer fictional depictions of Adolf Hitler’s early years (including the 2014 novel HUNTERS IN THE SNOW by D.M. Thomas and the 2003 film MAX). For that matter, THE NEW ADVENTURES OF HITLER’s main narrative hook was one that had already been utilized by the British novelist Beryl Bainbridge (in 1978’s YOUNG ADOLPH): an alleged 1912-13 sojourn in Liverpool by a young Adolph Hitler, as was claimed (falsely) by Hilter’s sister-in-law Bridget.

It was in Liverpool, Morrison alleges, that Hitler’s future course was decided. His obsession here is with the “Holy Grail,” which he eventually finds, albeit in a wholly unexpected form. Along the way Morrison gives his trademarked surrealism full reign in panels like those in which Hitler discovers Morrissey singing in his closet and has his future obliquely foretold by a strange man bearing a dog with uncontrollable diarrhea.

The illustrations by Steve Yeowell are instrumental to the series’ overall effect. Yeowell freely utilizes 60s-era psychedelia in the form of swirling wallpaper design that periodically recurs in the backgrounds of many panels, and impressionistic splashes of light and darkness that potently flesh out the young Adolph Hitler’s unsettled mindset.

It’s all quite memorable, with the depiction of Hitler residing in England, historically inaccurate though it may be, providing a disturbing parallel to the political climate in today’s English speaking world. Morrison’s overriding message seems to be that, quite simply, it can happen here, and based on our recent history I’ll have to agree.