Looking back over the disease movies of years past we find a great deal of fancy, certainly, but also some reality, stemming from the fact that many of those films were directly inspired by actual outbreaks. The bubonic plague has been an especially popular subject in films ranging from Ingmar Bergman’s THE SEVENTH SEAL (DET SJUNDE INSEGLET; 1957) to the Roger Corman Poe adaptation THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (1964), the New Zealand science fiction themed THE NAVIGATOR: A MEDIEVAL ODYSSEY (1988), the Norwegian epic TROLLSYN (1994), the British horror movie BLACK DEATH (2010) and the Spanish TV series LA PESTE (2018-19). Those titles are all set in a proper medieval time frame, and deal with the bubonic plague—which, as we’ll see, is different from the less common (but more dramatic) pneumonic plague.

Cinema’s earliest years were relatively quiet from a disease standpoint. Given that film began as a peepshow attraction rather than a legitimate art form (a state to which many would claim the medium has returned), viruses were unacceptable subject matter, especially given that the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 was an occurrence escapist-minded viewers probably weren’t eager to re-experience in filmic form. Yet the specter of disease couldn’t help but creep into the entertainment of the silent era.

Given that film began as a peepshow attraction rather than a legitimate art form (a state to which many would claim the medium has returned), viruses were unacceptable subject matter…

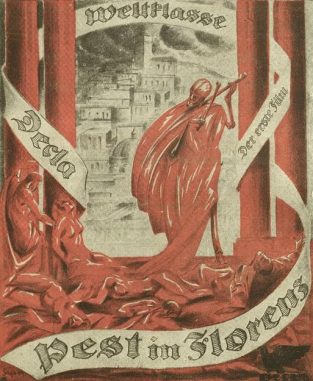

See the German made DIE PEST IN FLORENZ (THE PLAGUE IN FLORENCE) from 1919, a Fritz Lang  scripted, Edgar Allan Poe inspired period piece about a contagion that strikes the citizens of Florence due to their sinful lifestyles. The film is notable for solving something quite a few subsequent plague-themed films have struggled with, namely the query of how to effectively dramatize an antagonist that’s a). Soundless, b). Invisible and c). Inhuman. Here we’re given a spectral fiddle playing figure who serves as the personification of the contagion a la the ominous mask wearer of Poe’s classic tale.

scripted, Edgar Allan Poe inspired period piece about a contagion that strikes the citizens of Florence due to their sinful lifestyles. The film is notable for solving something quite a few subsequent plague-themed films have struggled with, namely the query of how to effectively dramatize an antagonist that’s a). Soundless, b). Invisible and c). Inhuman. Here we’re given a spectral fiddle playing figure who serves as the personification of the contagion a la the ominous mask wearer of Poe’s classic tale.

Disease was an especially popular subject of the Parisian Grand Guignol (or “Theater of Blood”) plays that flourished in the early years of the Twentieth Century, with one such play adapted for film in 1929: THE LIGHTHOUSE KEEPERS (GARDIENS DE PHARE). The film, directed by the great Jean Grémillon, it concerns a pair of sequestered men, one of whom is infected with the plague, a once-unthinkable state of affairs with which we can nowadays all relate.

The 1930s, cinema’s so-called golden age, were relatively quiet on the disease front, unless you count the decade’s many heroic doctor movies. These consisted of well-meaning prestige projects, some of them based on actual historical figures, about white-skinned medical practitioners attempting to fight disease in some foreign locale (being early examples of Hollywood’s much cherished “white savior” subgenre). See John Ford’s ARROWSMITH (1931), THE STORY OF LOUIS PASTEUR (1936), YELLOW JACK (1938), King Vidor’s THE CITADEL (1938) and the Nazi-financed ROBERT KOCH: THE BATTLE AGAINST DEATH (ROBERT KOCH, DER BEKAMPFER DES TODES; 1939).

The 1930s, cinema’s so-called golden age, were relatively quiet on the disease front, unless you count the decade’s many heroic doctor movies.

And the genre was by no means finished in the 1930s, finding echoes in the Rosalind Russel headlined biopic SISTER KENNY (1946), the Turkish SALGIN (1952), about the efforts of a heroic nurse to save as many lives as she can amid a plague, and THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN (1971). The latter, about an extraterrestrial pathogen that wipes out a town, focuses on the scientist protagonists fighting the pathogen, with the pandemic treated as a jumping-off point (video artist Anne McGuire’s 2002 restructuring of the film, STRAIN ANDROMEDA THE, which relates its events in reverse chronology, i.e. from containment to outbreak, actually seems more germane to this essay). And the heroic doctor subgenre continues to this day, with Aashiq Abu’s VIRUS appearing in 2019; it’s been described as “A real life account of the deadly Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala, and the courageous fight put on by several individuals which helped to contain the epidemic.”

Also related to the heroic doctor cycle is the Czech SKELETON ON HORSEBACK (BILA NEMOC) from 1937. Adapted from a play by Karel Capek, it’s about a pacifistic doctor (played by the film’s writer-director Hugo Haas) who discovers a cure for a disease affecting people over fifty, but refuses to disseminate it unless his country’s warmonger dictator (Zdenek Stepánek) ceases his military endeavors. The latter, as you might guess, isn’t too receptive to Haas’s overtures, in a film that never succeeds in overcoming its stage-bound origins, nor the naivety of its political convictions.

Also related to the heroic doctor cycle is the Czech SKELETON ON HORSEBACK (BILA NEMOC) from 1937. Adapted from a play by Karel Capek, it’s about a pacifistic doctor (played by the film’s writer-director Hugo Haas) who discovers a cure for a disease affecting people over fifty, but refuses to disseminate it unless his country’s warmonger dictator (Zdenek Stepánek) ceases his military endeavors. The latter, as you might guess, isn’t too receptive to Haas’s overtures, in a film that never succeeds in overcoming its stage-bound origins, nor the naivety of its political convictions.

The following year was the “Motion Pictures’ Greatest Year” 1938, the year SEX MADNESS was released (or at least 1938 is the copyright date it bears; it’s widely believed to have actually been made several years earlier). Made by Dwain Esper, a filmmaker who was not exactly know for great (or good) cinema, SEX MADNESS is very much in the vein of REEFER MADNESS from two years earlier, being a finger-wagging screed about the evils of venereal disease, 1930s style: choppy, wrong-headed, exploitive and outrageously dated.

The following year provided a decidedly xenophobic and class conscious depiction of disease in the form of PACIFIC LINER. About a cholera outbreak on a passenger ship in the Asiatic sea, its primary villain is an Asian stowaway who spreads the disease in the ship’s steerage portion, whose denizens are portrayed as brutish and unreasonable. The heroes are the ship’s good looking upper deck doctor (Chester Morris) and the gruff but loveable engineer (Victor McLaglen), whose level headedness help make things right (white saviors indeed!).

The Val Lewton produced, Mark Robson directed horror fest ISLE OF THE DEAD, from 1945, is considered a classic by many. Yet Robson was never the director Jacques Tourneur (of the Lewton productions CAT PEOPLE and I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE) was, and turns out a highly uneven film that for me only really comes alive in the final twenty minutes. It features a number of people, a Boris Karloff essayed Greek general among them, quarantined in a garrison on a small island after plague breaks out among them. The film’s most arresting portion involves a possibly undead woman whose presence provides some genuinely shivery moments.

Here we’ll jump forward to 1950. It was then that a pair of similarly themed film noirs, PANIC IN THE STREETS and THE KILLER THAT STALKED NEW YORK, appeared. The inspiration for both was a minor smallpox outbreak that occurred in New York City in March-April of 1947. That Hollywood was so eager to adapt this incident to film (however loosely) showed a definite change of attitude from the escapist mentality of earlier eras. As Twentieth Century Fox’s late chairman Darry F. Zanuck stated in 1943, “We must begin to deal realistically in film with the causes of war and panics, with social upheavals and depression, with starvation and want and injustice and barbarism under whatever guise.” This led to the “social consciousness” cycle of films, one of the top directors of which was Elia Kazan, who was tapped by Zanuck to helm PANIC IN THE STREETS.

Here we’ll jump forward to 1950. It was then that a pair of similarly themed film noirs, PANIC IN THE STREETS and THE KILLER THAT STALKED NEW YORK, appeared. The inspiration for both was a minor smallpox outbreak that occurred in New York City in March-April of 1947. That Hollywood was so eager to adapt this incident to film (however loosely) showed a definite change of attitude from the escapist mentality of earlier eras. As Twentieth Century Fox’s late chairman Darry F. Zanuck stated in 1943, “We must begin to deal realistically in film with the causes of war and panics, with social upheavals and depression, with starvation and want and injustice and barbarism under whatever guise.” This led to the “social consciousness” cycle of films, one of the top directors of which was Elia Kazan, who was tapped by Zanuck to helm PANIC IN THE STREETS.

“We must begin to deal realistically in film with the causes of war and panics, with social upheavals and depression, with starvation and want and injustice and barbarism under whatever guise.”

PANIC IN THE STREETS was the more upscale of the two films, with Richard Widmark as a Public Health Service officer tasked with containing an epidemic of pneumonic plague (which affects the lungs rather than the lymph nodes targeted by bubonic plague) in New Orleans. The script underwent heavy tampering at the hands of the censorship board, leaving us with an involving, visually exciting thriller that, alas, doesn’t go far enough. Widmark’s investigation into the spread of the disease, and the eventual eradication of same, seems far too easy, being over with in time for the climactic dock-set showdown with the main antagonist (Jack Palance), which is likewise wrapped up far too conveniently.

THE KILLER THAT STALKED NEW YORK was the more down and dirty B-movie take on the case, focusing on a young woman (Evelyn Keyes) infected with smallpox—the “killer” of the title—and unwittingly spreading it around New York. The invisible nature of the menace, and the fact that it’s spread unintentionally, necessitate the use of an off-screen narrator to fill us in on Keyes’s affliction—“She didn’t deliver death out of the end of a gun or the point of a knife, she delivered it wholesale just by walking through a crowd”—and a diamond smuggling subplot that barely registers. Like the former film, THE KILLER THAT STALKED NEW YORK is not all it could have been.

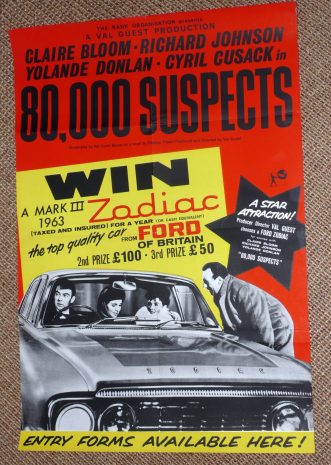

In the 1960s the Brits got into the act, in A MATTER OF WHO (1961) and 80,000 SUSPECTS (1963), both of  which are too polite and refined (read: British) for their own good. A MATTER OF WHO is about a smallpox patient at a London airport who causes a minor panic; starring the popular British comedian Terry Thomas, the pic is at least appealingly eccentric in its mixture of drama and comedy, and better than 80,000 SUSPECTS. Made by the prolific Val Guest (whose other credits include THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT, THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN and THE DAY THE EARTH CAUGHT FIRE), the latter is a not-very-thrilling thriller about a doctor (Richard Johnson) whose marriage to Claire Bloom is tested by a(nother) smallpox outbreak in the town of bath. For a smallpox drama done right see 1982’s VARIOLA VERA, a Yugoslavian production about a quarantined big city hospital that was loosely based on fact (in this case a 1972 smallpox outbreak in Belgrade). In contrast to the previous two films, this one is artful, horrific and overall feels very real.

which are too polite and refined (read: British) for their own good. A MATTER OF WHO is about a smallpox patient at a London airport who causes a minor panic; starring the popular British comedian Terry Thomas, the pic is at least appealingly eccentric in its mixture of drama and comedy, and better than 80,000 SUSPECTS. Made by the prolific Val Guest (whose other credits include THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT, THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN and THE DAY THE EARTH CAUGHT FIRE), the latter is a not-very-thrilling thriller about a doctor (Richard Johnson) whose marriage to Claire Bloom is tested by a(nother) smallpox outbreak in the town of bath. For a smallpox drama done right see 1982’s VARIOLA VERA, a Yugoslavian production about a quarantined big city hospital that was loosely based on fact (in this case a 1972 smallpox outbreak in Belgrade). In contrast to the previous two films, this one is artful, horrific and overall feels very real.

For a smallpox drama done right see 1982’s VARIOLA VERA, a Yugoslavian production about a quarantined big city hospital that was loosely based on fact (in this case a 1972 smallpox outbreak in Belgrade).

The same cannot be said for the decade’s other mainstream disease movie, the Alistair MacLean adapted THE SATAN BUG (1965). Directed by the skilled John Sturges, it’s an ersatz thriller, about the theft of two deadly airborne viruses from a research facility in the California desert, that suffers greatly from the conventions of the era (such as the overuse of tacky rear projection driving scenes).

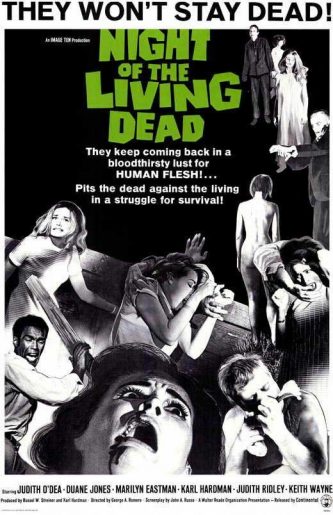

Appearing outside the mainstream was George Romero’s 1968 NIGHT OF LIVING DEAD, which combined the disease and undead motifs of ISLE OF THE DEAD in the form of a zombie contagion. The film is noteworthy first for kick-starting the zombie apocalypse trope, which has provided the subject matter for countless films in the years since (including Romero’s own DAWN and DAY OF THE DEAD, 28 DAYS LATER, RESIDENT EVIL, SHAUN OF THE DEAD, WORLD WAR Z and the long running cable series THE WALKING DEAD). It was by no means the “first” example of its type, having been admittedly influenced by a 1954 novel, Richard Matheson’s I AM LEGEND, that had already been adapted for the screen in the 1964 Vincent Price vehicle THE LAST MAN ON EARTH (and would be re-adapted in THE OMEGA MAN and I AM LEGEND). Yet NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD had a secret weapon that film, and most of its follow-ups, lacked: a perceived social significance.

Appearing outside the mainstream was George Romero’s 1968 NIGHT OF LIVING DEAD, which combined the disease and undead motifs of ISLE OF THE DEAD in the form of a zombie contagion. The film is noteworthy first for kick-starting the zombie apocalypse trope, which has provided the subject matter for countless films in the years since (including Romero’s own DAWN and DAY OF THE DEAD, 28 DAYS LATER, RESIDENT EVIL, SHAUN OF THE DEAD, WORLD WAR Z and the long running cable series THE WALKING DEAD). It was by no means the “first” example of its type, having been admittedly influenced by a 1954 novel, Richard Matheson’s I AM LEGEND, that had already been adapted for the screen in the 1964 Vincent Price vehicle THE LAST MAN ON EARTH (and would be re-adapted in THE OMEGA MAN and I AM LEGEND). Yet NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD had a secret weapon that film, and most of its follow-ups, lacked: a perceived social significance.

To hear Romero tell it, the fact that NOTLD featured a black man in the lead role wasn’t ever part of his plan (according to him, actor Duane Jones was cast simply because he was available), nor were the many (seeming) allusions to the realities of the late 1960s. Yet the film’s alleged sociopolitical resonance has been picked over at great length over the ensuing decades (fact: there are more books devoted to NOTLD than there are about CITIZEN KANE).

The fact that it was a B-movie, I’d argue, helps in this regard. Finding significance in exploitation fare is a popular pastime among pretentious film commentators (the late Robin Wood practically made a career out of it), as such films offer real entertainment value in place of the dreary self-importance of A-list pandemic movies like THE PLAGUE (LA PESTE; 1992) and BLINDNESS (2008). Those films, based on the similarly titled Albert Camus and Jose Saramago novels, proudly wore their social significance on their respective sleeves (I don’t think I’ve ever read a review of BLINDNESS, novel or film, that didn’t take pains to point out the epidemic of “white blindness” that drives its story is merely window dressing for Deeper Concerns), and were both hit with widespread critical and audience disinterest.

A major problem with the outsized reception afforded NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD was that Romero, like Hitchcock in his later years, apparently came to believe the hype. This is to say that he became obsessed with the sub-textual aspects of his films, to the point that in conceiving them he admittedly came up with the thematic content first, and then filled in the plot and characters.

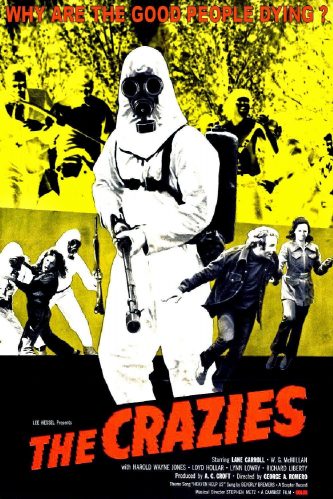

This explains why Romero had so much trouble interesting financiers in his later years (he’s nearly as famous for the many films he didn’t make as those he did), and may also account for THE CRAZIES (1973). About a contagion that turns the citizens of a small Pennsylvania town into maniacs, it’s an early example of the insanity plague trope that would become nearly as popular as the living dead one (see WARNING SIGN, IMPULSE, the Spanish REC and its Hollywood remake QUARANTINE, and KINGSMAN: THE SECRET SERVICE). Yet the film is curiously underwhelming overall, despite a kinetic treatment and some potent bloodletting.

QUARANTINED arrived in 1970. A small scale TV movie about a cholera epidemic that traps several doctors and a temperamental starlet (Sharon Farrell) in a hospital, it’s a far cry from the similarly plotted VARIOLA VERA, being soapy, melodramatic and quite timid in its depiction (or lack thereof) of the ravages of the disease. This puts it on par with subsequent disease-themed TVMs like JERICHO FEVER (1993), VIRUS (1995), CONTAGIOUS (1997), CARRIERS (1998), QUARANTINE (2000) and CONTAINMENT (2015), all of which mined disease movie tropes that by the inception of the 1990s were clichés.

Speaking of popular tropes: SURVIVORS was a BBC series that ran for three seasons, starting in 1975 and concluding in ‘77. It was followed in 1978 by the publication of Stephen King’s epic novel THE STAND, about a “superflu” that wipes out most of humanity, leaving the few surviving humans to battle it out among themselves; the novel was revised in 1990, and in 1994 was adapted for a high profile Mick Garris directed TV miniseries.

SURVIVORS and THE STAND are notable as early attempts at a trend that has become quite prevalent in apocalypse movies, with pandemics taking the place of nuclear wars as agents of the apocalypse. Such a switch was made quite blatantly in Terry Gilliam’s 12 MONKEYS (1995), a remake of Chris Marker’s science fiction classic LA JETEE (1962); in that film the world was destroyed by war, whereas in 12 MONKEYS it’s a man-made pathogen (whose theft figures into a SATAN BUG like subplot) that does the honors. Having humanity wiped out by a virus, alas, tends to lessen the fun of such accounts, at least for those of us who agree with Clive Barker’s statement that “I like my apocalypses to contain giant insects.”

SURVIVORS and THE STAND are notable as early attempts at a trend that has become quite prevalent in apocalypse movies, with pandemics taking the place of nuclear wars as agents of the apocalypse. Such a switch was made quite blatantly in Terry Gilliam’s 12 MONKEYS (1995), a remake of Chris Marker’s science fiction classic LA JETEE (1962); in that film the world was destroyed by war, whereas in 12 MONKEYS it’s a man-made pathogen (whose theft figures into a SATAN BUG like subplot) that does the honors. Having humanity wiped out by a virus, alas, tends to lessen the fun of such accounts, at least for those of us who agree with Clive Barker’s statement that “I like my apocalypses to contain giant insects.”

Yet THE STAND miniseries wasn’t bad. A bit bloated (as was the book) and subdued (an inevitability given the demands of network TV censors), perhaps, but on the whole a gripping piece of work. Ditto SURVIVORS, about a virus that kills nearly everyone in Britain, leaving the scattered survivors attempting to subside in a primitive and unforgiving world. Interesting, but from what I’ve seen of the series I say it could have done with some giant insects.

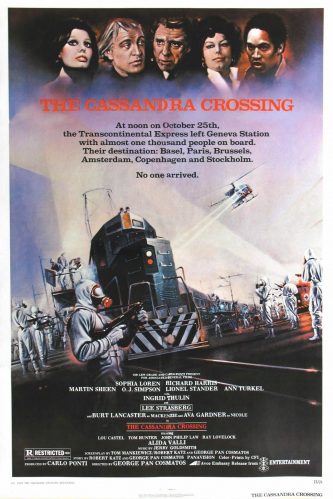

With the Italian made THE CASSANDRA CROSSING (1976) disease, in the form of (once again) the  pneumonic plague, was utilized in service of the popular disaster movie model of the era. Here, in place of the malfunctioning airplanes, bug swarms, volcanoes, burning high rises and earthquakes that packed other seventies blockbusters we have a train, stocked by an all-star cast, upon which a plague-ridden man has stowed away. Mass sickness and a quarantine result, although director George P. Cosmatos (the future helmer of RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II and TOMBSTONE) is clearly more interested in commonplace action and destruction. Ultimately THE CASSANDRA CROSSING has more in common with another Italian import, the 1967 spaghetti western DJANGO KILL! (SE SEI VIVO SPARA), which used plague as a throwaway plot point in its overtly gothic account of a spectral gunslinger, than it does with PANIC IN THE STREETS or THE KILLER THAT STALKED NEW YORK.

pneumonic plague, was utilized in service of the popular disaster movie model of the era. Here, in place of the malfunctioning airplanes, bug swarms, volcanoes, burning high rises and earthquakes that packed other seventies blockbusters we have a train, stocked by an all-star cast, upon which a plague-ridden man has stowed away. Mass sickness and a quarantine result, although director George P. Cosmatos (the future helmer of RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II and TOMBSTONE) is clearly more interested in commonplace action and destruction. Ultimately THE CASSANDRA CROSSING has more in common with another Italian import, the 1967 spaghetti western DJANGO KILL! (SE SEI VIVO SPARA), which used plague as a throwaway plot point in its overtly gothic account of a spectral gunslinger, than it does with PANIC IN THE STREETS or THE KILLER THAT STALKED NEW YORK.

In July of 1976 an outbreak of what came to be known as Legionnaires’ disease—an especially severe orm of pneumonia—sickened 182 people, 29 of which died, at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia. While there doesn’t appear to be any direct connection to the mini-flood of disease themed movies that followed, this much-publicized incident set the tone quite adequately for what was to come.

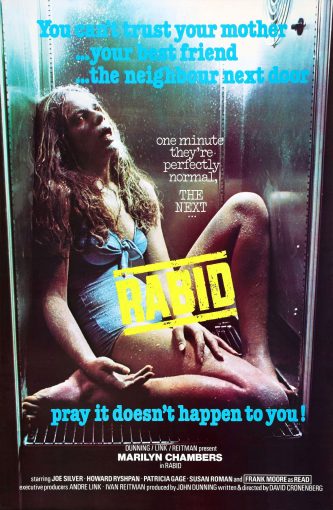

Among that flood of late-1970s disease thrillers were David Cronenberg’s Canadian exploiter RABID (1977) and PLAGUE (1979), another Canadian made grindhouse item. Neither film is perfect, but both have plenty to recommend.

Among that flood of late-1970s disease thrillers were David Cronenberg’s Canadian exploiter RABID (1977) and PLAGUE (1979), another Canadian made grindhouse item. Neither film is perfect, but both have plenty to recommend.

RABID is somewhat unbalanced, with a downright nutty set-up involving a young woman (Marilyn Chambers) getting a skin graft that causes a vampiric organ to grow out of her armpit, precipitating a rabies contagion in a final third that, in contrast to the earlier scenes, is genuinely alarming. THE PLAGUE suffers yet again from the fact that its antagonist, a young plague infected woman (Céline Lomez) wandering the Canadian countryside, lacks the requisite drama and menace. The film gains power from, interestingly enough, its tiny details, such as a close up of Lomez smearing blood on a door handle and a shot of a bare-handed butcher making a sandwich while she hovers nearby.

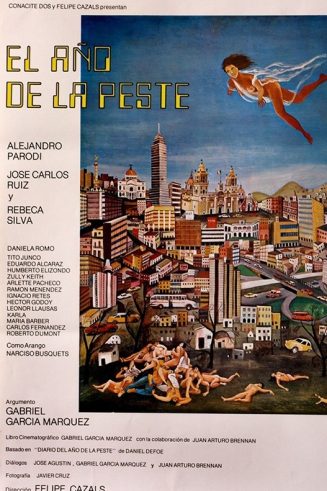

EL AÑO DE LA PESTE (THE YEAR OF THE PLAGUE; 1979) is an especially apocalyptic pandemic film from Mexico that had in its favor a script by the renowned novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Loosely adapted from A JOURNAL OF THE PLAGUE YEARS by Daniel Dafoe, it contains all the visceral detail one could ask for— masses of plague-felled corpses being scooped into a truck, hazmat suited men patrolling the streets—and also the philosophical edge one would expect given Marquez’s pedigree. Unfortunately that latter element far outweighs the former, which is to the film’s detriment.

masses of plague-felled corpses being scooped into a truck, hazmat suited men patrolling the streets—and also the philosophical edge one would expect given Marquez’s pedigree. Unfortunately that latter element far outweighs the former, which is to the film’s detriment.

The eighties ushered in an anything-goes approach to virus cinema. Bequeathed, seemingly, by Peter Fleischmann’s bizarre 1979 French-German co-production THE HAMBURG SYNDROME—which spiced its more-or-less straightforward account of a pandemic sweeping the titular city with various quirky and surreal details—this new, non-reality based approach was fully in keeping with the falsely optimistic don’t-worry-be-happy gist of the Reagan era. Little did we know that a very real contagion was already with us, a contagion that by the end of the decade would make its way to the forefront of our consciousness regardless of how much cocaine-fueled optimism we exuded.

The first eighties-era disease movie out of the gate was the 1980 Japanese mega-production VIRUS, or DAY OF RESURRECTION (FUKKATSU NO HI), which can be considered the HOW THE WEST WAS WON of virus movies. Featured are an all-star cast, a decades-spanning narrative that encompasses multiple languages and continents, and some elaborate (for 1980) special effects to flesh out its depiction of a world threatened by an especially deadly pathogen. Unfortunately director Kinji Fukasaku tends to mistake spectacle for drama, and has trouble maintaining interest over his rather protracted 156 minute runtime (pared down greatly for VIRUS’S American release).

In 1983 we got the so-so BBC miniseries THE MAD DEATH, about a rabies outbreak in England. It’s closer to DAY OF THE ANIMALS (1977) than RABID, focusing more on the potentially dangerous canines threatening the populace, and how best to contain them, than the virus itself. Not much better was Lars von Trier’s Danish oddity EPIDEMIC (1987), which ostensibly concerns itself with a city ravaged by plague. Trier, however, seems more concerned with postmodern trickery, in the form of a screenwriter and director (Von Trier and his co-screenwriter Niels Vørsel) discussing the story being depicted; this is supposed to lead to a clash of “reality” and invention, but neither strand is very interesting.

In 1983 we got the so-so BBC miniseries THE MAD DEATH, about a rabies outbreak in England. It’s closer to DAY OF THE ANIMALS (1977) than RABID, focusing more on the potentially dangerous canines threatening the populace, and how best to contain them, than the virus itself. Not much better was Lars von Trier’s Danish oddity EPIDEMIC (1987), which ostensibly concerns itself with a city ravaged by plague. Trier, however, seems more concerned with postmodern trickery, in the form of a screenwriter and director (Von Trier and his co-screenwriter Niels Vørsel) discussing the story being depicted; this is supposed to lead to a clash of “reality” and invention, but neither strand is very interesting.

The American made low budgeter THE CARRIER (1988) is more straightforward in its approach but ultimately just as esoteric, being about a disease that causes people to liquefy after touching contaminated surfaces. This somehow leads to the populace of a small town covering themselves with trash bags, cats stuck to walls and other oddness.

Then there was the notorious Hong Kong WWII set period piece MEN BEHIND THE SUN (HEI TAI YANG 731) from 1988, depicting, in great detail, the unspeakable tortures doled out to Chinese prisoners by Japanese troops in the testing of biological weapons. The film was remade (in a fashion) in 2008 by Russian’s Andrey Iskanov, as the four-hour PHILOSOPHY OF A KNIFE, which believe it or not is even more gruesome and exploitive.

The 1990s saw a new sort of disease narrative that explicitly referenced the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, which many likened to a new black plague. AIDS themed cinema formally commenced in 1985, with the groundbreaking NBC TV movie AN EARLY FROST, and would come to include a couple of cable TV movies (the 1993 releases AND THE BAND PLAYED ON and DAYBREAK) and a Hollywood drama (1993’s PHILADELPHIA), but the most powerful film to emerge from this cycle emerged from an unexpected place: the American independent film scene that gave us SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE and SLACKER. LONGTIME COMPANION may not be as well-known but has arguably held up better than either, and is, despite its prestige drama trappings, very much a plague movie in its unnerving depiction of a tightknit group of gay men in San Francisco whose numbers gradually decrease as they succumb to a mysterious unknown disease.

AIDS may also have played a part in the conception of the suicide plague of 1991’s LAST FRANKENSTEIN (RASUTO FURANKENSHUTAIN), a truly outré Japanese updating of Mary Shelley’s immortal classic, and the even odder Taiwanese offering THE HOLE (DONG; 1998), in which Taiwan is afflicted by a strange disease that causes its sufferers to act like insects. For more Asian madness see the post-apocalyptic oddity ERI ERI SABAKUTANI (2005), which focuses on a pair of musicians attempting to make music from found objects in the midst of a horrific pandemic.

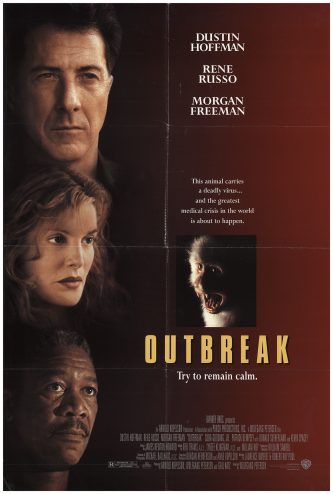

Onto the mid-nineties, when a terrifying new virus was unveiled. It was in late ‘94 that Richard Preston’s bestselling nonfiction tome THE HOT ZONE was published; the book explored an outbreak of Ebola, an African originated disease very few survive, in the United States. The film rights were quickly snapped up by Hollywood, with two competing projects put into production: a Robert Redford starrer called HOT ZONE and a Harrison Ford vehicle named OUTBREAK. The latter, with Ford replaced by Dustin Hoffman, was greenlit first, causing HOT ZONE to be scuttled—although a quickie 1995 TV movie entitled VIRUS, directed by the veteran trash-meister Armand , arose from its ashes.

VIRUS, as you might guess, wasn’t much, but OUTBREAK was. It utilized the facts recounted by Preston (a horrific airplane flight in particular) in service of a Hollyweird noise-maker that leaves “reality” far behind. Nonetheless, it was the first movie to explore the minutiae of disease prevention in our time, a far cry from the know-it-all scientific milieu of THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN and the movie star heroics of THE CASSANDRA CROSSING and VIRUS; the principals of OUTBREAK may be played by big names like Hoffman, Rene Russo and Cuba Gooding Jr., but that doesn’t render them immune from the “Motaba” virus (as Ebola was for some reason renamed in the film).

VIRUS, as you might guess, wasn’t much, but OUTBREAK was. It utilized the facts recounted by Preston (a horrific airplane flight in particular) in service of a Hollyweird noise-maker that leaves “reality” far behind. Nonetheless, it was the first movie to explore the minutiae of disease prevention in our time, a far cry from the know-it-all scientific milieu of THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN and the movie star heroics of THE CASSANDRA CROSSING and VIRUS; the principals of OUTBREAK may be played by big names like Hoffman, Rene Russo and Cuba Gooding Jr., but that doesn’t render them immune from the “Motaba” virus (as Ebola was for some reason renamed in the film).

Also noteworthy is the film’s groundbreaking use of digital effects in an early scene in a movie theater, in which we follow the spittle of an infected person through the air and into other people’s mouths. The effect was utilized once again—i.e. copied—in the 2013 South Korean film FLU, which was just as overwrought and melodramatic as OUTBREAK (among its protagonists is a cute little girl) but utilized a much greater canvas, albeit to considerably lesser effect.

1996 brought the Hong Kong category III (i.e. adults only) outrage EBOLA SYNDROME, which offered a much trashier, more exploitive take on the Ebola threat. Among the film’s delicacies are murder, rape, dismemberment, child abuse, necrophilia and cannibalism, all of which are nearly overshadowed by the specter of an Ebola-infected protagonist, of which there are, truly, few things more terrifying.

The 2000s brought a new roster of diseases to our attention, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Avian Influenza, or Bird Flu. The latter caused a fair amount of media hysteria (and a bad 2006 TV movie entitled FATAL CONTACT: BIRD FLU IN AMERICA) but turned out to be fairly benign in its impact, although the SARS virus, a viral agent of which makes up the coronavirus (or SARS-CoV-2), was a bit more serious, at least in China and Hong Kong.

It was there that a 2003 compilation DVD of short films, entitled 1:99, was made by a number of Hong Kong filmmakers in response to the virus. The overall tone is one of dogged (or misplaced?) optimism, with comic pieces, such as one in which a SARS afflicted woman coaches her son from a hospital bed on what moves to make in a Mah-Jong game, and much darker ones, as in an especially bleak segment in which HK superstar Tony Leung finds himself stuck in a deserted city where hundreds of face mask wearing people stare out at him from the windows of surrounding buildings.

The other major concern of the early 00s was, of course, terrorism. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 spurred widespread anxiety about future attacks of the biological variety, including a 2002 panic over the possibility of a smallpox attack.

That panic was manifested in the BBC telefilm SMALLPOX 2002: SILENT WEAPON. The advertising tagline assured us that “The events are real. It just hasn’t happened yet,” which clues us in on the film’s format: a mock-documentary made, allegedly, in the future year 2005 about a terrorist initiated smallpox epidemic that occurred in 2002. The nonfiction construct is well carried off, with suitably hyperbolic narration by Brian Cox, copious interviews with various experts medical and otherwise, and actual news footage recontextualized to show what happened in the dark days of ‘02. Depicted are mass riots, food shortages and New York City grinding to a halt (sound familiar?).

Not to be outdone, the National Film Board of Canada put out a companion-piece of sorts in the form of 2010’s OUTBREAK: ANATOMY OF A PLAGUE, which likewise utilized a mock-documentary approach in depicting a smallpox epidemic. Intercut with a straightforward History Channel-esque presentation of the 1885 smallpox outbreak in Toronto, it shows how a modern-day flight attendant becomes an unwitting carrier of the virus, which once again ravages Toronto. The film is far less ambitious than SMALLPOX 2002, and ultimately works  better as a history lesson than a predictor of future events.

better as a history lesson than a predictor of future events.

The same post-9/11 anxiety that brought us SMALLPOX 2002 produced RIGHT AT YOUR DOOR, an American indie from 2006. Set near Dodgers’ Stadium in LA, its depiction of the initial chaos ensuing from the detonation of a “dirty bomb” is affecting, but even more so are the later scenes in which the protagonist (Rory Cochrane) attempts to self-isolate from his wife (Mary McCormack), who’s been exposed to the contagion.

There were more virus movies in the 00s, including 2002’s overhyped horror-fest CABIN FEVER (Eli Roth), the 2008 TV miniseries remake of THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN and the apocalyptic indie CARRIERS from 2009 (it was actually made three years earlier but not released until ‘09 in order the capitalize on the late-in-the-decade stardom of cast member Chris Pine). The key virus movie our age, however, didn’t arrive until 2011.

Steven Soderbergh’s CONTAGION is the film that, out of all those mentioned here, is most accurate to our current situation. It provides a step-by-step depiction of how a deadly Asian-born contagion takes root in America, sickens a great many people and leads to a societal breakdown, all while a group of desperate MDs attempt to contain the spread of the virus and find a cure. It’s not perfect, bearing the tell-tale signs of a hasty production (Soderbergh admittedly likes to shoot very fast), while the script, based on what we now know about pandemics, leaves out a number of pertinent issues, such as the economic upheavals that result from the contagion. But the film works.

The 2010s saw the rise of televised virus dramas. There was the Belgian series CORDON in 2014, in which the city of Antwerp is cordoned off by the government after a contagion breaks out therein, and its Americanized remake CONTAINMENT in 2016, which changed the setting to Atlanta, GA, as well as a six episode miniseries adaptation of THE HOT ZONE in 2019. The South Korean miniseries THE VIRUS represented a minor highlight in this category, with an exciting ten part depiction of an odd young man who carries a deadly virus with a 100 percent fatality rate. The series’ first half, focusing on the hunt for the carrier, is admittedly more involving than the second, about a corrupt pharmaceutical outfit profiting off the disease (a western outfit, of course).

The 2010s saw the rise of televised virus dramas.

According to an article on the Clinical Infections Diseases website, “A virus that can eradicate humanity is a film subject waiting for a cinematic and scientific masterpiece.” Clearly we’re going to have to keep waiting, because despite some standout virus-themed films—NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, VARIOLA VERA, LONGTIME COMPANION, CONTAGION—there are no real masterpieces to be found amid the aforementioned bunch of films. A better question would be about how much we’ve learned from the accumulated wisdom (much of it useless but some of it vital) contained in these films. Based on our response thus far to the Coronavirus pandemic, I’d say the only true answer to that question is: absolutely nothing.