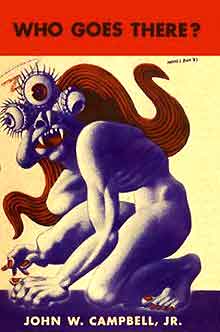

The saga of what is now commonly known as THE THING has a 70-plus year history that, not unlike the unstoppable shape-shifting “Thing” itself, encompasses quite a few varied permutations. It all began in 1938, with the publication of John W. Campbell’s novella “Who Goes There?” in Astounding Stories (under the pseudonym Don A. Stuart).

A justified classic, “Who Goes There?” boasts a unique and (literally) chilling Antarctic setting (a setting that also proved invaluable to H.P. Lovecraft’s AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS, published two years earlier). There a group of scientific researchers discover a frozen creature they determine was a passenger on a space ship that crashed into the ice millions of years earlier. The critter is a frightful three-eyed monstrosity with wormy tentacles for hair—which the researchers unwisely take back to their nearby compound.

In short order the thing disappears from where it was laid down, only to reappear in the facility’s canine pen, where it appears to be transforming into a dog. The men conclude the monster is a shape shifter that survives by becoming other living things, even going so far as to replicate its hosts’ personalities and thought patterns.

Paranoia suffuses the compound’s 37 inhabitants until one of them, the burly McReady, comes up with an ingenious way to root the thing out: take blood from each of the men and then jab it with a hot wire. Seeing as how the Thing’s every molecule is alive, the infected blood will react to the heat. This is indeed what occurs, and several faux-men are discovered before a final confrontation with the thing, which assumes its original three-eyed alien form (apparently the guise of the residents of another planet it previously visited) in time for McReady to decisively put it out of commission with a flame-thrower.

The tale is a strong one, even if it is painfully dated in most respects. It’s also overly talky, taken up largely with people explaining things; as always in his fiction, Campbell’s chief concern was scientific plausibility, and he all-but bludgeons us with endless details of the thing’s molecular makeup. Yet the ingenuity of the concept is undeniable—remember, “Who Goes There?” appeared over a decade prior to similarly themed works like Jack Finney’s THE BODY SNATCHERS and Robert Heinlein’s THE PUPPET MASTERS—and even if the tale no longer possesses the “incomparable suspense” it apparently once had, it still contains a distinct fascination, not to mention a uniquely stark and forbidding setting.

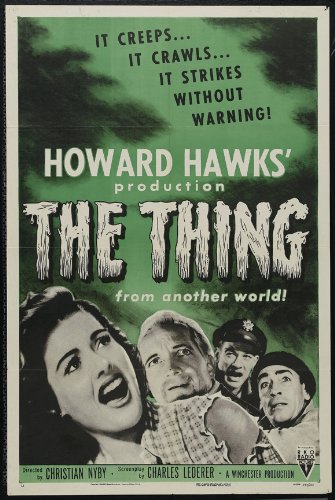

The first cinematic adaptation of the story, 1951’s THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD, was an extremely loose one. Produced and, it’s been widely alleged, directed by Howard Hawks (the credited helmer is Hawks’ longtime editor Christian Nyby), the film all-but dispenses with Campbell’s Thing, substituting it with, essentially, a humanoid plant that thrives on blood.

The setting was also changed, from Antarctica to the North Pole. The scientists here don’t have to worry about the thing imitating them, just that it might break into their compound and kill ‘em. This leads to much Hawksian male camaraderie among the scientists, and some muted suspense as they attempt to figure out a way to outwit and destroy the thing in their midst-–a particularly clever addition is a motion sensing Geiger counter that appears to have inspired a similar device in ALIENS (1986). In the end, of course, Yankee ingenuity wins out, with the thing walking into a carefully laid trap and winding up electrocuted, and one of the scientists radioing his superiors to intone the film’s last and most famous line: “Keep watching the skies!”

THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD was a sizeable success in 1951, out-grossing two other iconic science fiction dramas released that same year: THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL and WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE (both superior films in my view). These days it feels stodgy, with an overly leisurely narrative and a goofy-looking monster: a tall guy in a dopey mask and clawed gloves.

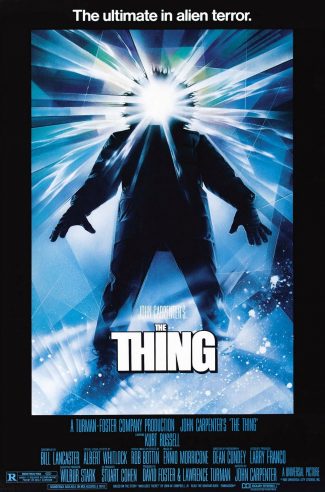

Longtime Howard Hawks admirer John Carpenter remade THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD in 1982, in expansive big budget form, as THE THING. In this film Carpenter paid only cursory attention to the earlier THING, instead lavishing his attention on “Who Goes There?”

As in the story, the setting is the icy expanse of Antarctica, superbly evoked by Carpenter and cinematographer Dean Cundy. The character names are taken from Campbell’s original, with Carpenter’s frequent headliner Kurt Russell playing McReady.

The one major departure from the story is that here the scientists happen upon the thing indirectly, via a dog from a Norwegian outpost depleted by the thing. The dog is placed in a pen with several other dogs, where, as in the story, it undergoes a horrific transformation.

It’s here that THE THING’S raison d’etre (and most controversial aspect) comes in: the Rob Bottin designed special effects. Bottin’s stunning pre-CGI work, encompassing severed body parts, splitting torsos, exploding eyeballs and tendril-sprouting severed heads, remains unsurpassed for imagination and execution, even if it has been imitated to death (in Abel Ferrara’s BODY SNATCHERS, THE FACULTY, Carpenter’s own IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS and all the NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET films, to name but a few examples).

Yet the film, in contrast to what so many of its critics allege, is also exceedingly suspenseful and atmospheric. Carpenter’s trademarked spare, old-fashioned filmmaking works quite well here, in what is perhaps the finest cinematic depiction of people trapped in an enclosed space since Luis Bunuel’s classic THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL (1962). The film is a triumph of style, suspense and real terror.

While on the subject of John Carpenter’s THING, we should also take a look at the 1981 novelization of THE THING by Alan Dean Foster. The book bears quite a few pratfalls common to movie novelizations—oft-hasty prose, perfunctory descriptions, an overall first draft feel—yet is easily the most inspired Foster novelization I’ve read. Another interesting facet of this novel is the fact that it was taken from an early draft of Bill Lancaster’s THING script, and so differs from the finished film in quite a few aspects.

Foster does a fine job depicting the chill and monotony of his characters’ lives, with McReady becoming quite infatuated with his blow up doll companion (an element that didn’t make it into the finished film). The horrific action is also generally well handled, although it’s here that the novel’s shortcomings are most evident. The final chapters, wherein the sensational aspects—or “whammies”—increasingly dominate the narrative, simply don’t evince the same care as the more cerebral portions. Yet Alan Dead Foster knew what he was doing, and taken as a whole THE THING is about as readable, lively and well-rounded a take on Carpenter’s film as can be expected.

That film, unfortunately, was not a success. It opened in the summer of ‘82, alongside Steven Spielberg’s more uplifting alien encounter movie E.T., and I don’t think I need to tell you which film made more money. Nor was THE THING especially popular with the critics: for years it was singled out by old fart commentators (along with Paul Schrader’s 1982 CAT PEOPLE remake) to demonstrate the apparent superiority of suggestive, non-explicit horror of the 1940s and 50s over the more modern type. The problem with this argument is that THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD a). was more science fiction-themed than horror, b). wasn’t all that “suggestive” in its approach, and c). was, frankly, not a better film than Carpenter’s.

What a difference a couple decades makes! THE THING is now widely recognized as a classic by many, and no wonder: in the midst of all the CGI-packed noise-fests currently clogging the multiplexes, Carpenter’s film seems restrained and even stately in its approach. Many modern commentators have even detected a political subtext in its narrative, which some view as a metaphor of 80s-era conformity, while the blood test scene, closely patterned after the equivalent passage in “Who Goes There?,” now seems like an oblique commentary on AIDS.

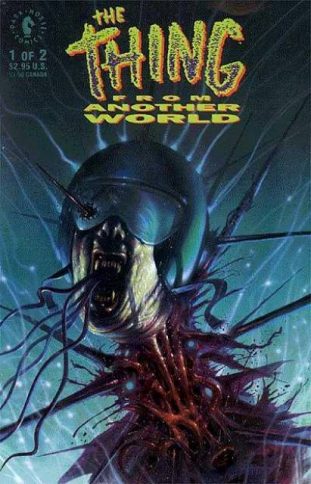

Over the years there have been quite few proposed sequels to Carpenter’s masterpiece, including an abandoned 2003 Sci Fi Channel mini-series and a proposal by John Carpenter himself that evidently never got beyond the conceptual stage. As it happened, two separate THING sequels came to fruition, though both occurred outside the film arena: a 2002 video game for PC, Playstation 2 and Xbox that I haven’t played, and four comic book miniseries from Dark Horse.

I’ve read the first of those comic minis, 1991’s 2-issue THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD (titled so as not to conflict with FANTASTIC FOUR’s the Thing). It picks up where the film left off, with the surviving protagonists McReady and Childs lost in the wilds of Antarctica. Childs leaves McReady with the crew of a passing whaling ship, where the latter steals a helicopter. Flying back to the site of his destroyed compound, McReady meets up with some Navy Seals, one of whom is the Thing. What follows is a chaotic mélange of shooting, explosions and gory transformations. McReady eventually meets back up with Childs, who turns out not to be infected—unfortunately, it seems that just about everyone around them is.

The scripter Chuck Pfarrer is a Hollywood screenwriter, and his THING reads very much like an eighties-era Hollywood actioner in its (over)emphasis on firepower and machismo. The painterly artwork by John Higgins is quite eye-pleasing but for the depictions of the title critter, a toothy bug-like monstrosity that looks more like something out of ALIEN than the imagination of Rob Bottin (whose creations are as distinct and artistic as those of nearly anyone). In short, this THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD, despite its creators’ best efforts, is a disappointment.

Speaking of non-cinematic offshoots of THE THING, Peter Watts’ immensely intelligent and subversive 2010 short story “The Things” ranks high. The story recounts the events of Carpenter’s film from the Thing’s point of view. This enormously thoughtful and introspective creature is puzzled, if not outright shocked, by the behavior of the people it encounters after its spacecraft crash lands in Antarctica. The Thing views its assimilation into other life-forms as a joyous and ecstatic form of communion (seeing itself as “a soldier, at war with entropy itself”) and can’t understand why humans so steadfastly resist it.

Combining a strong grasp of hard science with wildly fanciful speculation, “The Things” is a triumph in every respect. It will make little sense to readers who haven’t seen the film, but those familiar with Carpenter’s classic will experience a thoughtful and appropriately reverential take on the material that’s certain to enhance one’s understanding and appreciation of THE THING.

Getting back to the cinematic arena, we arrive at, last but definitely least, the 2011 THING prequel. This new THING, however, is actually a thinly disguised remake of Carpenter’s masterpiece. Despite certain cosmetic changes—a babe scientist (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) in the lead role, a climactic immersion inside the alien spaceship seen briefly in the original—this THING hits nearly all the same beats as its predecessor, from an early scene in a dog pen to a crucial test to see who among the protagonists is the thing (accomplished, in the film’s only truly original addition, via the sight of teeth fillings the thing can’t assimilate) to a fateful rec room confrontation with two guys tied up.

What’s missing is the tautness and suspense of Carpenter’s filmmaking, which Matthijs van Heijningen Jr.’s bland direction doesn’t come close to equaling, as well as the wizardly creature design of Rob Bottin. Certainly the digital effects here far outdo Bottin’s in frequency and elaborateness, yet none of these “improved” effects are as memorable as the original THING’S sight of a severed head sprouting tendrils and scuttling across a floor—a strong example of the primacy of in-camera special effects (however primitive) over CGI.

Are there any more THING offshoots visible on the horizon? Not at the moment (unsurprisingly, the ‘11 THING didn’t exactly light the box office on fire), but based on all that has come before, I can’t help but conclude that more will be heard from the Thing, and sooner than you think.