By CARL GOTTLIEB (Newmarket Press; 1975/2001/05)

By CARL GOTTLIEB (Newmarket Press; 1975/2001/05)

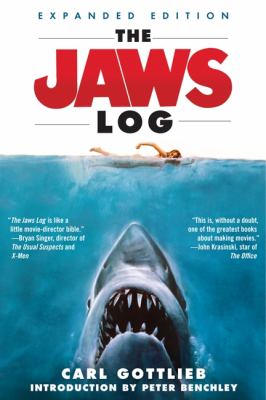

First things first: THE JAWS LOG is not, as the back cover of the 2005 edition wrongfully claims, “the only book on how twenty-six year old Steven Spielberg transformed Peter Benchley’s number-one bestselling novel into the classic film it became” (see also THE MAKING OF THE MOVIE JAWS by Edith Blake), but it is the best, being an admirably frank, succinct and compulsively readable account pulled off with a great deal of self-effacing humor. It’s a relic from an era when movie making-of books contained real—and not always flattering—information about the films they chronicled, unlike the studio-vetted puff pieces we get nowadays.

Carl Gottlieb was the screenwriter of JAWS, although, as he freely acknowledges in these pages, he got the job only after several attempts at adapting Peter Benchley’s novel had been made by Benchley himself and playwright Howard Sackler. Gottlieb was also present for the calamitous Martha’s Vinyard shoot, and provides an unflinching first-hand account of the experience.

Gottlieb warns upfront that his memory of the events described isn’t entirely accurate, but his claims generally mesh with those of most every other account I’ve uncovered about the making of JAWS. Here we learn that the film rights to Benchley’s text were snapped up by producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown before it was even published, and the novel’s monster success on the marketplace, which occurred while the movie was being filmed, was a major reason Universal’s overseers refrained from pulling the plug on JAWS’S increasingly chaotic production.

Among the problems faced by Spielberg and his collaborators were hostile Martha’s Vinyard locals, whose antics included extortion, stealing equipment and putting bullets through the front door of the house rented by JAWS’S late co-star Robert Shaw. There was also the matter of the mechanical shark who essayed the title role, which was never ready in time and caused all manner of production delays (being a primary reason the critter is so little seen in the finished film).

Dwarfing those things, however, was the time spent filming at sea, which, as subsequent ocean-set productions have proven (WATERWORLD, anyone?) is always a dicey proposition. Among the problems the crew faced on the open sea were consistently unpredictable weather and a horizon that was rarely ever clear (the days when things could be digitally erased were a long way off). This led to widespread tension and anxiety among the cast and crew, with crewmembers callously killing tiger sharks in revenge for the problems the movie’s shark was causing, star Roy Scheider flipping out near the end of the production and Spielberg suffering an anxiety attack.

The 2005 edition of this book includes extensive footnotes that provide updates to the 30 year old text, which is obviously a bit out of date. It’s in these newly written footnotes that we learn the final cost of JAWS came to around $11 million, that the Martha’s Vinyard locals who had bit parts in the movie have been well compensated over the years in the form of lucrative residual checks, and that a pivotal underwater scene was filmed in the backyard swimming pool of JAWS’ editor Verna Fields. It all adds up to an indispensable volume that’s must reading for anyone interested in JAWS, or moviemaking in general.