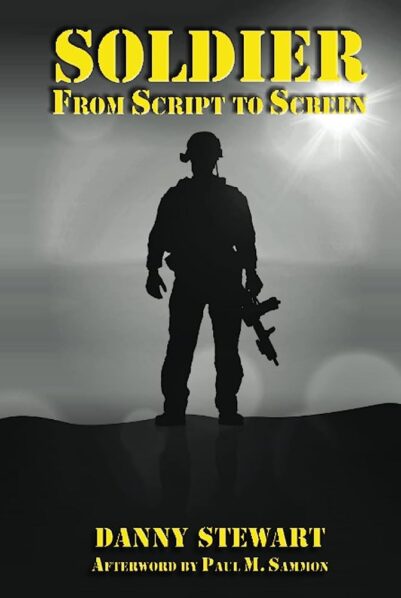

By DANNY STEWART (Bear Manor Media; 2023)

I’ve admittedly never been too enthusiastic about the 1998 Kurt Russell science fiction vehicle SOLDIER, but thoroughly enjoyed this passionate account of its making. It’s a Bear Manor Media movie book, and an above-average example. In contrast to others, such as Declan Neil Fernandez’s scholarly-oriented HORRIBLE AND FASCINATING—JOHN BOORMAN’S EXORCIST II: THE HERETIC and Paul Downey’s unruly THE SHARK IS ROARING—THE STORY OF JAWS: THE REVENGE, Danny Stewart’s SOLDIER: FROM SCRIPT TO SCREEN is straightforward and no-nonsense, featuring in-depth interviews with quite a few of SOLDIER’S crewmembers and critical analyses by Stewart, John Hansen, Mark Stratton and John Kenneth Muir. Spoiler alert: if you were hoping for a cynical deconstruction a la the abovementioned Fernandez and Downey books you’ll be disappointed, as SOLDIER’S shoot, despite some logistical challenges, was apparently a harmonious one, with the only major note of conflict, it seems, having been co-star Gary Busey (not a fellow known for his restraint).

Moreover, Stewart really reveres SOLDIER, and makes an impassioned case for its brilliance. An early chapter places it in the company of MAD MAX, ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK, ROBOCOP and UNFORGIVEN, as SOLDIER was, like them, a neo-western pastiche. Its basis was a David Webb Peoples script that Stewart brands “a true genre landmark” (Peoples, for the record, also scripted BLADE RUNNER and UNFORGIVEN).

Peoples is among the interviewees, providing his recollections of the development and production of SOLDIER. Claiming to have conceived it after viewing THE TERMINATOR in 1984, and written the initial draft that same year, he flatly denies that it was ever intended as a sequel to BLADE RUNNER or a remake of SHANE (although the film’s director Paul W.S. Anderson apparently thought differently). Peoples also laments that “the studio didn’t get” his screenplay, and that he’s never seen the finished film.

Other interviewees include associate producer Fred Fontana, production designer David L. Snyder, actor Mark Bringleson and visual effects supervisor Van Ling. Fontana calls the film’s main set, built on the Warner Bros. studio lot, “one of the most impressive sets I’ve ever seen,” while Snyder discusses how his job of production designer differed from that of his art director duties on BLADE RUNNER—“It takes many skills to be a production designer, as opposed to an art director. A lot of it has to do with politics”—and Ling admits he never actually met Kurt Russell or Paul W.S. Anderson, having spent the entirety of his employment in post-production.

This is all undeniably compelling. I may not care for SOLDIER (I tend to agree with author Paul M. Sammon, who in an afterword to the present book takes the film to task for its “pedestrian direction, misjudged horror flourishes, and a listless pace”), but the enthusiasm of Stewart and his collaborators is infectious, and makes me wonder if a personal reappraisal might be in order.