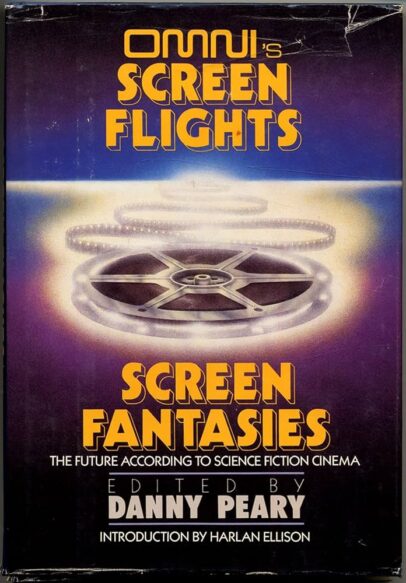

Edited by DANNY PEARY (Doubleday; 1984)

This now four-decades-old OMNI Magazine sponsored anthology was once the single greatest print resource for science fiction cinema. The only reason the book has lost that distinction is because it’s so dated, with important science fiction films that appeared after its publication such as THE TERMINATOR (1984), ROBOCOP (1987) and THE MATRIX (1999), going undiscussed. For its time, though, the Danny-Peary-edited OMNI’S SCREEN FLIGHTS/SCREEN FANTASIES offered the most exhaustive take on big screen sci fi in existence, covering not just classics of the form like FORBIDDEN PLANET and 2001 (although both are discussed at some length), but also lesser-known releases like TERIMNAL ISLAND (1973), CAFÉ FLESH (1982) and the genre excursions of England’s Peter Watkins and Russia’s Andrei Tarkovsky.

The book commences with an introduction by Harlan Ellison, who offers a highly opinionated overview of science fiction cinema in which OUTLAND (1981) is dismissed as “monkey-puke” (Ellison takes a second shot at the film in an essay appearing elsewhere in the book), THE THING (1982) as a “deranged beast of a film” and the STAR WARS trilogy as “nothing more than adolescent wish fulfillment, and if we have no more of it we’ll have had enough.” There follow over thirty highly learned essays by an assortment of critics, novelists and directors, and a handful of interviews with sci-fi movie luminaries like Roger Corman, Michael Crichton, Ridley Scott and Tarkovsky.

Highlights include Isaac Asimov’s “Movie Science,” in which Asimov gauges the accuracy of sci fi cinema’s imaginings, with the asteroid field flythrough in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK and the forest chase in RETURN OF THE JEDI dismissed because “human reaction time is actually so slow that neither the asteroids nor the trees can possibly be avoided.” I particularly enjoyed “A Cannibalized Novel Becomes SOYLENT GREEN,” in which author Harry Harrison gives his none-too-effusive opinion on the big screen adaptation of his novel MAKE ROOM! MAKE ROOM!, and also the late Dan O’Bannon’s “The Remaking of DARK STAR,” in which he details the making of that 1974 no-budget wonder. More brainy goodness is provided by Robert Silverberg’s “The Way the Future Looks: THX-1138 and BLADE RUNNER,” which compares two very distinct films that each “create a landscape of the mind, vivid and compelling and complete, that for one breathless moment of suspension of disbelief seems to be the real thing…”

Also of interest are “The Master and METROPOLIS” by Robert Bloch, who pens a loving tribute to that 1927 classic, based on Bloch’s own friendship with its director Fritz Lang. In “NO BLADE OF GRASS: A Warning for Our Time,” Cornel Wilde writes of how his self-directed apocalyptic drama NO BLADE OF GRASS (1970) became more relevant in the years following its release, while in “Thoughts on How Science Fiction Films Depict the Future” THE DAY AFTER (1983) director Nicholas Mayer offers up the book’s shortest piece, stating that, quite simply, THE DAY AFTER and most all post-nuke movies are completely inaccurate because they feature survivors, when in actuality a nuclear conflict would leave no one standing. That’s a point echoed by MAD MAX (1979) director George Miller in “Directing MAD MAX and THE ROAD WARRIOR,” in which the witty and intelligent Miller is interviewed by Peary.

There are no unworthy entries (although “Mathemagicians: Computer Moviemakers of the 1980s and Beyond,” in which journalist Tom Onosko writes about early 1980s digital technology, comes close), making this book a must-read, dated though it may be. I’d also recommend tracking down some back issues of the no-longer-extant science magazine that provided the title heading, as its quality standards were similarly lofty.