By MARIO MASINI (Damocle; 2020)

By MARIO MASINI (Damocle; 2020)

One of the more pleasantly surprising developments of 2020 was the inrush of attention paid to the work of Italy’s late Carmelo Bene, who was previously all-but unknown in the English speaking world. A true iconoclast, Bene was an actor, playwright, novelist and filmmaker who in his films (as in his life) favored the ridiculous, the outlandish and the extreme.

A true iconoclast, Bene was an actor, playwright, novelist and filmmaker who in his films (as in his life) favored the ridiculous, the outlandish and the extreme.

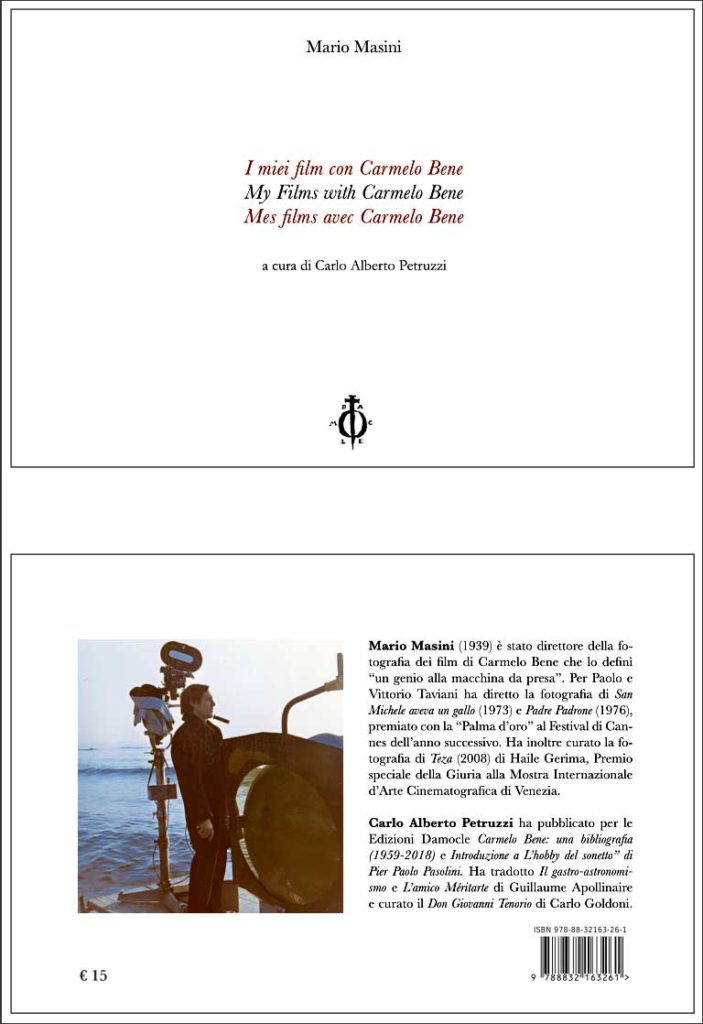

MY FILMS WITH CARMELO BENE consists of oral testimony by Mario Masini, the cinematographer on four of Bene’s five feature films, transcribed by Carlo Alberto Petruzzi. A trilingual book, it is quite short, consisting of about thirty pages of text printed in Italian, English (translated by Carole Viers-Andronico, who also Anglicized Bene’s autobiographical I APPEARED TO THE MADONNA) and French, followed by Bene and Masini filmographies, and ten pages of behind the scenes photos. I say Masini could have gone on a lot longer about his relationship, personal and professional, with Mr. Bene, but given the dearth of English language Bene resources this book ranks as a must-read for anyone with even the slightest interest in the films of this neglected genius—although as Masini admits in these pages, “Only a small number of people appreciated his films.” Hopefully this book will go some way toward changing that.

“Only a small number of people appreciated his films.”

Masini claims he first met Bene in 1967. Masini had just been fired from a film project and Bene was gearing up to make his debut feature NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI (1968). Masini ended up photographing the film, upon which he and Bene developed a mental bond that proved quite useful given that Bene worked without a script and was a compulsive improviser.

Masini went on to photograph Bene’s subsequent films DON GIOVANNI (1970), SALOME (1972) and UN AMLETO DI MENO (1973), all of which were subject to the same eccentric conditions under which Bene had lensed his debut. The major difference was that Bene and Masini had greater financial support on the latter two films, which were shot in Italy’s prestigious Cinecitta studio.

Once again: a longer and more detailed treatment would have been preferable, but Masini provides a good overview of his Bene collaborations, and some fun tidbits. The superimpositions of NOSTRA SIGNORA DEI TURCHI, he claims, were apparently accomplished via a pane of glass held in front of the camera, while in another scene some peasant villagers mistook the film’s co-star (and longtime Bene GF) Lydia Mancinelli for the Madonna. Masini also reveals that the filming of DON GIOVANNI took place entirely in Bene and Mancinelli’s tiny apartment, and that a tampon “spurting out” of a naked extra ruined a shot in SALOME, and that Bene made use of a soot-covered wall for the UN AMLETO DI MENO shoot after said wall unexpectedly caught fire. We also get a brief remembrance of an aborted Bene filming of FAUST that was to involve live tigers, and another prospective feature entitled GIUSEPPE DESA DA COPERTINO, which was pronounced “unmakeable” due to an unprecedented two camera shoot conceived by Bene.

We also get a brief remembrance of an aborted Bene filming of FAUST that was to involve live tigers…

In closing Masini states that “I hope, with these pages, I was able to provide a glimpse into Carmelo’s cinematic experience, which remains unprecedented in the history of cinema.” As a longtime Bene fan, I completely agree. I also concur with Masini’s parting observation that “We need to get back our sense of irony, to get back our sense of sarcasm, and to get back to making fools of ourselves. In short, we need someone like Carmelo.”