By DOUGLAS E. WINTER (Berkley; 1985)

By DOUGLAS E. WINTER (Berkley; 1985)

This is perhaps the key nonfiction text of the Horror Boom of the 1970s and 80s. Patterned after Charles Platt’s science fiction based DREAM MAKERS anthologies, FACES OF FEAR consists of mini-profiles of seventeen horror writers by the prolific critic, anthologist and sometime novelist (and fulltime attorney) Douglas E. Winter.

This is perhaps the key nonfiction text of the Horror Boom of the 1970s and 80s.

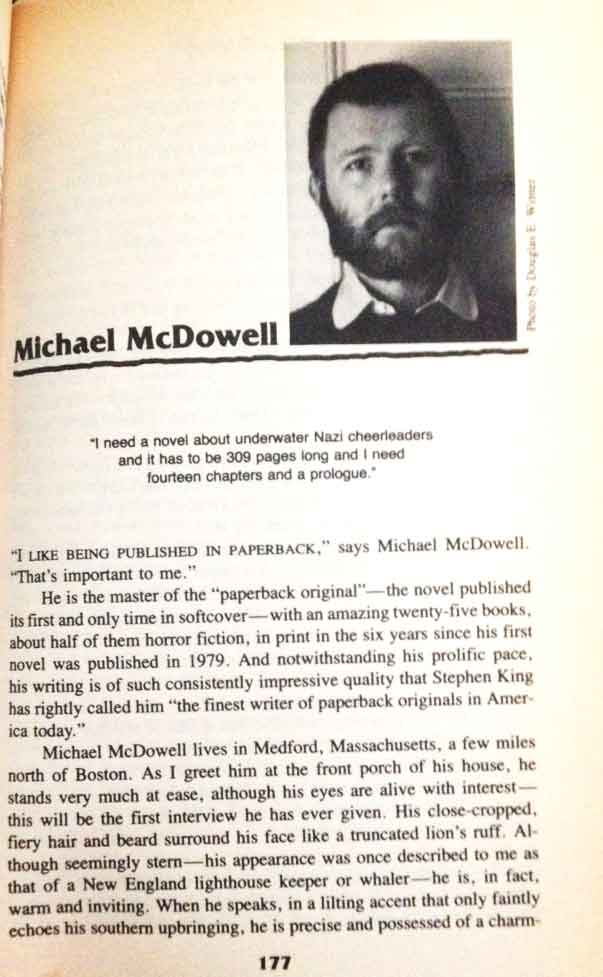

The book begins with coverage of the old-timers Robert Bloch, Richard Matheson and William Peter Blatty, and concludes with (then) young turks like Michael McDowell and Clive Barker, while the two final slots are given over to the decade’s most prominent horror writers: Peter Straub and Stephen King. The latter chapter is formatted differently from the others, consisting of an interview with King in which he, in contrast to the ordinary guy persona he likes to present, comes off as quite disturbed, airing any number of phobias and anxieties (“Every day, when I wake up and turn on the news, I wait for someone to say that Paris was obliterated last night”), and admitting “I’ve remained quasi-suicidal all the time.”

“Every day, when I wake up and turn on the news, I wait for someone to say that Paris was obliterated last night.”

Of the rest of the writers, there are definite similarities. Nearly all are men (with the late V.C. Andrews, who takes pains to distance herself from the horror label, being the sole female) and, this being a 1980s publication, all are white—although, for the record, there were non-white horror writers active in 1985, such as Joseph Nazel and S.P. Somtow. For that matter, there were quite a few Caucasian horror scribes who go MIA here, including Charles Beaumont, T.M. Wright, Dean Koontz and Jack Ketchum.

Of the rest of the writers, there are definite similarities. Nearly all are men (with the late V.C. Andrews, who takes pains to distance herself from the horror label, being the sole female) and, this being a 1980s publication, all are white—although, for the record, there were non-white horror writers active in 1985, such as Joseph Nazel and S.P. Somtow. For that matter, there were quite a few Caucasian horror scribes who go MIA here, including Charles Beaumont, T.M. Wright, Dean Koontz and Jack Ketchum.

Anyway: Bloch, Matheson and Blatty, unsurprisingly, tend to rail against explicit violence in fiction. As Matheson states, “When you feel like averting your face, that’s not frightening, that’s revolting” (quite a contrast with Barker’s claim that “I like to be able to deliver the vileness. There’s never going to be any evasion”). That sentiment is echoed by the late “Quiet Horror” adherent (and notorious curmudgeon) Charles L. Grant, who states “I really wonder if the people who made FRIDAY THE THIRTEENTH have any respect for themselves…I don’t think I’d want to meet them. They are not my kind of people.”

…this being a 1980s publication, all are white—although, for the record, there were non-white horror writers active in 1985, such as Joseph Nazel and S.P. Somtow.

Lapsed or nonexistent religious beliefs are further commonalities (religion being an evident obsession with Winter, who underwent a strict Southern Baptist upbringing), as is anti-elitism. Barker is especially pointed in his claims that “I think it would be much healthier if the Sunday Times reviewed the books which people are reading, instead of those being read by a very small percentage of the general public.” The late Alan Ryan (whose first interview this was) goes even farther, rubbishing the very idea of “art” (apparently “a nineteenth century concept”) and proclaiming “I don’t think it’s embarrassing to make money. I don’t think it’s embarrassing to be on the bestseller list. I don’t think it’s embarrassing to be popular.” A definite case of wishful thinking, as during his lifetime Ryan never made much money, didn’t appear on any bestseller lists and wasn’t too popular.

“When you feel like averting your face, that’s not frightening, that’s revolting.” (Quite a contrast with Barker’s claim that “I like to be able to deliver the vileness. There’s never going to be any evasion”).

Where these authors differ is on the age-old question of why anyone would want to write horror. John Coyne admits he turned to it because “I wanted to write a book that had a built-in audience,” while King opines that “I guess it’s just my fate” he became a genre novelist. Childhood experiences are another frequently discussed topic, with Ramsey Campbell leading the way in horrific upbringings (as enumerated in his famous introduction to THE FACE THAT MUST DIE). Whitley Strieber also has some disturbing childhood recollections, although I feel we have reason to disbelieve his claims (see below).

Where these authors differ is on the age-old question of why anyone would want to write horror.

Obviously there are portions that seem politically incorrect by modern standards, as when Grant rails against a hypothetical “fanatical feminist” around whom he has to “watch every word that I utter for fear of offending her with a “sexist” remark. Well, shit on that—a broad is a broad.” The most controversial portion concerns Strieber, who makes an ass of Winter and himself, with Winter beginning his chapter on Strieber with an apparently “true” recollection about how he was caught up in the 1966 Charles Whitman shooting spree, a story Strieber has since admitted was bullcrap (blaming it on “screen memories” brought about by the aliens he says abducted him).

Yet ultimately, controversy or not, there’s plenty to enjoy in this book. Plus, those of you with an interest in horror fiction, and the 1980s fiction market, simply won’t find a more authoritative resource.