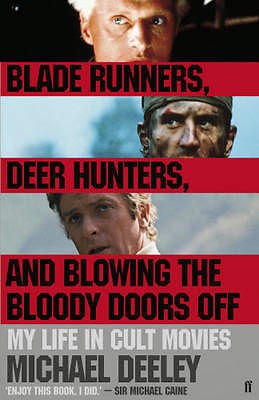

By MICHAEL DEELEY (Faber and Faber; 2008)

By MICHAEL DEELEY (Faber and Faber; 2008)

A likeable and enjoyable memoir by Michael Deeley, a prolific British movie producer whose films have nearly all attained cult status. Those movies include the original ITALIAN JOB, THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH, THE DEER HUNTER, BLADE RUNNER and the iconic 1970s horror films THE WICKER MAN and DON’T LOOK NOW.

The book commences with perhaps the shortest forward in history penned by Ridley Scott, who asserts that “A producer’s life is not for the faint-hearted.” From there Michael Deeley keeps things moving right along, wisely limiting his childhood reminisces and revelations about his personal life (which in all frankness doesn’t seem very interesting). Throughout, the focus is exactly where it should be: on the many films Deeley produced.

The book commences with perhaps the shortest forward in history penned by Ridley Scott, who asserts that “A producer’s life is not for the faint-hearted.”

Deeley got his start in the nudie film industry of the early 1960s, which led to the production of director Richard Lester’s successful THE KNACK…AND HOW TO GET IT, along with assorted oddities like ONE-WAY PENDULUM, SLEEP IS LOVELY and THE LONG DAY’S DYING. Then there was THE ITALIAN JOB, which is little known here in the U.S. but has become quite iconic in Britain. This explains why Deeley devotes several chapters’ worth of verbiage—a bit overmuch if you ask me—to the film’s preparation, filming and reception.

Following this apparent triumph was the Peter O’Toole headlined WWII picture MURPHY’S WAR, whose calamitous Venezuela shoot was, according to Deeley, “the toughest I have ever experienced.” Next Deeley wound up heading British Lion Films, and so was directly responsible for the recutting of THE WICKER MAN, which pissed off many aficionados of that film as well as its star Christopher Lee. Deeley defends his actions on the grounds that its British distributor demanded the film be shortened, and that “In making a picture, certain tough choices and compromises are often inevitable.”

As for DON’T LOOK NOW, Deeley recounts arguing with Warren Beatty, the then-boyfriend of co-star Julie Christie, over its infamously graphic sex scene. The film’s severely botched U.S. release was apparently due to the fact that it was hastily shunted into theaters in place of JONATHAN LIVINGSTON SEAGULL(!) after outraged theater owners demanded the latter be replaced with “anything that wasn’t about a seagull.”

Further misadventures occurred during the making of THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH, whose shoot was subject to the famously eccentric whims of its director Nicolas Roeg, while Sam Peckinpah was in the throes of cocaine-induced psychosis on Deeley’s production of CONVOY, and THE DEER HUNTER was marred by its duplicitous and egomaniacal helmer Michael Cimino. Of the latter film’s Best Picture Academy Award, Deeley sneers that “the only flaw I find in my Oscar is that Michael Cimino’s name is also engraved on it.”

This leads to the production of BLADE RUNNER, Deeley’s favorite of his films, which like THE ITALIAN JOB takes up several chapters. The problem is that most of the anecdotes related here were already told in Paul M. Sammon’s more authoritative 1996 book FUTURE NOIR: THE MAKING OF BLADE RUNNER—although there is at least one fresh remembrance involving Deeley barring from the set a “friend of Harrison Ford” who turns out to be a very annoyed Steven Spielberg.

Following BLADE RUNNER’S unsuccessful initial release Deeley commenced a retirement of sorts. He couldn’t stay away from movies for long, however, and immersed himself in the 1990s made-for-TV arena. During that period he produced Volker Schlondorff’s well-received racial drama A GATHERING OF OLD MEN and endured diva-ish behavior from a young Julia Ormond on the TNT miniseries YOUNG CATHERINE, which turned out to be Deeley’s final production.

All of the above adds up to an entertaining read for film buffs curious about precisely what a movie producer–specifically a British movie producer—does. No, this isn’t the greatest book about making movies I’ve ever read, but it’s far from the worst.