By W.A. HARBINSON (Custom Books Publishing; 2011)

By W.A. HARBINSON (Custom Books Publishing; 2011)

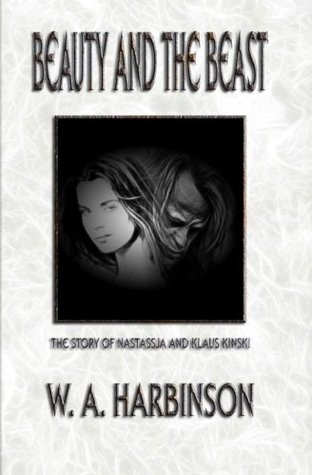

With this self-published book author W.A. Harbinson has hit upon a topic of unquestioned dramatic intensity: the story of actor Klaus Kinski and his daughter Nastassja. Theirs is a saga as sordid and outrageous as nearly any fictional account you can imagine, with a cast of equally outsized supporting characters that includes Roman Polanski, James Toback, Werner Herzog and Francis Ford Coppola.

The late Klaus Kinski was the so-called “Beast of cinema,” the star of films great (AGUIRRE: THE WRATH OF GOD, NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE) and not-so (VENOM, CRAWLSPACE) whose debauched off-screen life was and remains the stuff of legend. His daughter Nastassja is an actress and world-renowned beauty who was once compared to Greta Garbo and Brigitte Bardot, yet has led extremely rocky personal and professional lives. Harbinson relates the Kinskis’ respective stories through various media sources—books, articles and interviews—without any direct contact with his sources (the first of whom died in 1991, while the second tends to keep to herself these days).

Harbinson’s characterization of Nastassja, as a “clever self-creation, a beautiful female Frankenstein, whose real talent was for attracting enormous media attention, no matter how little she may have warranted it,” seems an accurate assessment of an actress who never fulfilled the early promise she showed in 1979’s TESS yet nonetheless became one of the world’s most famous women (all the while maintaining a staunch anti-publicity stance). The author, alas, has a bit more trouble characterizing Klaus, relying overmuch on his memoirs for background info, despite the fact that, as Harbinson himself admits, those memoirs were highly sensationalized.

Yet Harbinson deserves credit for conclusively showing just how intertwined his subjects’ lives truly were. Neither Klaus or Nastassja ever admitted to any sort of co-dependency—it was something, in fact, that was strongly disavowed by both—yet the two lived quite close to one another in LA during the 1980s and shared a number of acquaintances (such as the aforementioned Polanski and Toback). Nastassja, for the record, estranged herself from Klaus, who in turn seems to have lavished the majority of his parental affections on his son Nikolai, but again, theirs was not a mutually exclusive relationship by any means.

Harbinson also succeeds in dredging up some facts of which I was previously unaware, such as the truth about the pulping of the initial US edition of Klaus’ memoir, which apparently came about not because of a lawsuit by Nastassja (as has been widely alleged) but, rather, a copyright dispute. Such revelations help smooth over many of the book’s shortcomings, some of which are the author’s fault (the 128 page length, which is far too scant to do its subjects justice) and some not (the fact that the revelations of Nastassja’s half-sister Pola about her father’s sexual abuse aren’t included in these pages, due to the fact that Pola Kinski didn’t make those claims until two years after BEAUTY AND THE BEAST was published). So it is, on balance, a recommended read.