Friedrich Durrenmatt’s 1957 novel DAS VERSPRECHEN, or THE PLEDGE, is perhaps the most cruel and sardonic crime novel ever written. It contains all the twisted wit and macabre invention that tend to characterize Durrenmatt’s other novels and plays—TRAPS, THE ASSIGNMENT, THE VISIT, THE PHYSICISTS, etc.—combined with a compulsive readability and ingeniously conceived narrative. Still, THE PLEDGE is very much a Friedrich Durrenmatt tale, meaning it’s anything but warm and cuddly; as Jack Nicholson, the star of director Sean Penn’s ‘00 film adaptation, has stated, “you can’t win with Durrenmatt.”

Friedrich Durrenmatt’s 1957 novel DAS VERSPRECHEN, or THE PLEDGE, is perhaps the most cruel and sardonic crime novel ever written. It contains all the twisted wit and macabre invention that tend to characterize Durrenmatt’s other novels and plays—TRAPS, THE ASSIGNMENT, THE VISIT, THE PHYSICISTS, etc.—combined with a compulsive readability and ingeniously conceived narrative. Still, THE PLEDGE is very much a Friedrich Durrenmatt tale, meaning it’s anything but warm and cuddly; as Jack Nicholson, the star of director Sean Penn’s ‘00 film adaptation, has stated, “you can’t win with Durrenmatt.”

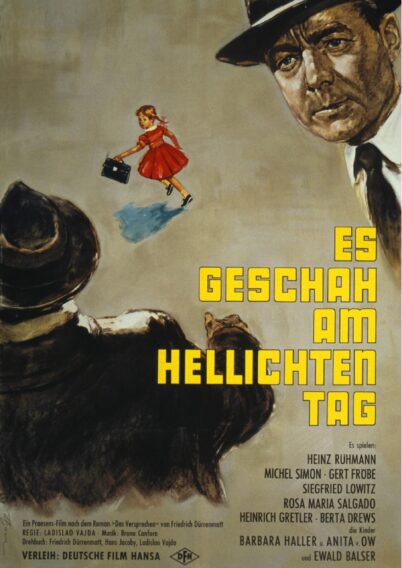

In truth THE PLEDGE began life as a novelization of sorts of the 1958 German film ES GESCHAH AM HELLICHTEN TAG, or IT HAPPENED IN BROAD DAYLIGHT, which was partially scripted by Durrenmatt. He apparently worked on both media simultaneously, with the novel representing his preferred take on the material.

THE PLEDGE is first and foremost a furiously readable book, related in short, intensely focused chapters. The hero is Matthai, a deeply methodical, determined detective not unlike those we’ve come to admire in movies ranging from THE FRENCH CONNECTION to DIE HARD. As with those films’ protagonists, Matthai isn’t above bending rules and going against his fellows’ findings in his all-consuming pursuit of justice.

Matthai has made a pledge to the mother of a murdered child that he’ll track down the killer, and he isn’t about to break that promise. Matthai’s relentlessly methodical approach to his profession, and life itself, has been unexpectedly replaced by an all-consuming sense of purpose, and he takes to this newfound passion a bit too whole-heartedly.

Matthai’s descent into obsession and insanity is seen from the point of view of his police chief—known to us as Dr. H—who finds himself alarmed at Matthai’s increasingly erratic behavior. Among other things, Matthai blows off a scheduled plane trip, buys a rural gas station and adopts a young girl named Annemarie. She’s the bait Matthai is using to lure the killer, whose path, Matthai is convinced, will intersect with his gas station at some point.

Despite his reservations, Dr. H participates in a Matthai-led sting operation that entails spying on Annemarie as she awaits the promised arrival of a “wizard.” This operation concludes in a particularly Durrenmattian bit of dark comedy when, after days of waiting for the killer to show up, the detectives grow fed up and take out their frustrations by beating up on poor Annemarie. What they don’t know is that the killer died in a car accident on his way to the meeting. This latter fact is eventually discovered by Dr. H independently of Matthai, thus rendering the latter’s crusade at once on-target and futile.

Another striking bit of dark comedy is Matthai’s reaction upon learning that his adopted daughter has been fraternizing with the killer, news Matthai  receives with “an enormous happiness” that his suspicions have been confirmed. Perhaps the most unforgettable bit of comedic mirth, however, occurs in a soliloquy Dr. H gives near the end of the book, in which he imagines an alternate version of the story “so uplifting and positive that it will just have to be published or turned into a film in the near future.”

receives with “an enormous happiness” that his suspicions have been confirmed. Perhaps the most unforgettable bit of comedic mirth, however, occurs in a soliloquy Dr. H gives near the end of the book, in which he imagines an alternate version of the story “so uplifting and positive that it will just have to be published or turned into a film in the near future.”

That film did indeed arrive in the near future, and with all the promised alterations. For starters, there’s no pledge in IT HAPPENED IN BROAD DAYLIGHT, with Matthai robbed of the book’s raison d’etre. As played by Heinz Ruhmann, the film’s Matthai is a far nicer guy, freed of the dark obsessions that drove his counterpart in THE PLEDGE.

In the film Matthai’s bad behavior is excused by the end-justifies-the-means climax, in which, to further quote from THE PLEDGE’s climactic monologue, Matthai “is no longer able to continue with his plan of using the child as bait, whereupon he could take Annemarie and her mother out of harm’s way and put a big doll” in the girl’s place. From there “a huge, solemn figure would come striding out of the forest, straight up to the look-alike doll…then, realizing he had fallen into a diabolic trap, (the figure) would fly into a rage, a fit of madness, there’d be a fight with Matthai and the police…” By the end of it all, “hope is rewarded, faith triumphs, and the story becomes acceptable for the Christian world.” I couldn’t have summed up the final scenes of the film better myself!

Nearly all the story’s rough edges have been blunted in IT HAPPENED IN BROAD DAYLIGHT, arguably the most perverse of THE PLEDGE’S movie incarnations. Yet taken as is the film actually works fairly well, being sprightly paced, suspenseful and atmospheric. In fact, if anything can truly be said to mar the film it’s the annoying conventions of the time—noisy music cues that sound whenever some big event occurs, hammy-by-modern-standards performances—more than its divergences from the novel.

performances—more than its divergences from the novel.

There were three more screen adaptations of Durrenmatt’s masterpiece following IT HAPPENED IN BROAD DAYLIGHT (actually five, if you count 1979’s poorly regarded LA PROMESSA and the equally maligned 1997 German TV remake of IT HAPPENED IN BROAD DAYLIGHT, both of which I’ll skip over). It took 32 years for the first of those adaptations, the Hungarian SZURKULET, or TWILIGHT, to reach screens in 1990.

This TWILIGHT, scripted and directed by the late György Fehér, is not to be confused with the better known book/movie franchise of that name, being a severely arty and affected film very much in the mold of Fehér’s fellow countryman Bela Tarr (who’s listed in the end credits as a “Consultant”). Some critics call Fehér’s TWILIGHT an epoch defining masterpiece and others a pretentious waste of time. I feel there’s justification for both views.

Fehér’s magisterial visuals are a wonder to behold, pulled off in a series of lengthy single takes and lensed in (deliberately) hazy black-and-white. The effect is profoundly eerie and foreboding, imparting the texture of a dimly recalled nightmare. But such filmmaking requires a great deal of painstaking effort, which is all too clear in this severely labored, deeply ponderous film (any and all scenic beauty has been drained from the mountain locations, and the actors all affect unwavering scowls).

As for Durrenmatt’s story, Fehér utilizes only bits and parts, winding up with a disjointed and confusing narrative. Storytelling clearly wasn’t the primary  concern, taking a back seat to the brooding imagery and overall mood of hallucinatory apprehension, which is, again, pulled off with undeniable flair.

concern, taking a back seat to the brooding imagery and overall mood of hallucinatory apprehension, which is, again, pulled off with undeniable flair.

1996 brought the British made COLD LIGHT OF DAY, a somewhat more faithful rendering of Durrenmatt’s tale. It will likely play best to viewers unfamiliar with the novel or the other adaptations, being a low budget affair that lacks the inspiration and visual splendor that characterize the previous films.

Still, there are compensations in the form of a strong performance by Richard E. Grant, who’s appropriately obsessive in the lead role, and some interesting twists that don’t appear in any of the other versions. This is the only one of the PLEDGE films to give the surrogate daughter any sort of personality, sharply conveying the loneliness and disillusionment that lead the girl into the arms of the killer (among other traumas, she spots Grant and her mother having sex). But the tacked-on action-oriented finale (involving a car crash, a foot chase and hokey cop-killer mano-a-mano) and happily-ever-after fade-out are a far, far cry from Durrenmatt.

The same cannot be said for Sean Penn’s THE PLEDGE, which follows Durrenmatt’s narrative fairly closely. The locale and timeframe have been transposed from fifties-era Zurich to the scenic wilderness of Nevada and Utah (actually British Columbia) in the final days of the 20th Century, but otherwise the new film’s screenwriters Jerzy Kromolowski and Mary Olson-Kromolowski (with uncredited assistance from Penn) are admirably faithful to the novel’s tone and narrative arc.

An immensely watchable Jack Nicholson essays the Matthias role, here remonikered Jerry Black. Jerry’s descent into madness is in many respects even bleaker than that of Durrenmatt’s hero, as Penn, unlike Durrenmatt, continually taunts us with the possibility that Jerry might settle down with the mother of his adopted daughter and overcome his obsessions. He doesn’t, alas, which greatly upset critics and audiences who found the film’s arc overly grim; as LOS ANGELES TIMES critic Kenneth Turan bemoaned, “sitting through this long dirge of a movie is like walking inexorably toward an execution that feels suspiciously like our own.”

The film, however, is a strong one: nuanced, absorbing and visually bold. The cinematographer was the great Chris Menges, whose supremely colorful imagery is nearly as impressive as TWILIGHT’S austere black-and-white visuals. The many distracting cameos by Penn’s Hollywood pals (including Benicio del Toro, Helen Mirren, Vanessa Redgrave, Harry Dean Stanton and Mickey Rourke, who it seems is on hand solely so we can see him cry) are an irritant, but in most all other aspects Penn displays enormous skill and an uncompromising commitment to his dark vision, which accords quite harmoniously with Durrenmatt’s.

Regarding the film’s much contested ending, I’ll have to borrow yet another portion of the novel’s climactic monologue quoted above: “Matthai would actually find a murderer…some sectarian preacher with a heart of gold who is, of course, innocent and incapable of doing evil, and just for that reason…he would attract every shred of suspicion the plot has to offer.” The apparent killer here is indeed a preacher, who according to actor Tom Noonan was not supposed to be the actual culprit but became so after harsh weather and a tight budget prevented a scene identifying the real killer from being shot.

Yet THE PLEDGE works. So do its predecessors IT HAPPENED IN BROAD DAYLIGHT, TWILIGHT and THE COLD LIGHT OF DAY, which despite their respective flaws have much to recommend. Do not, however, let them distract you from Friedrich Durrenmatt’s novel, which remains the fullest expression of this shocking, bleakly ironic and disquieting tale.