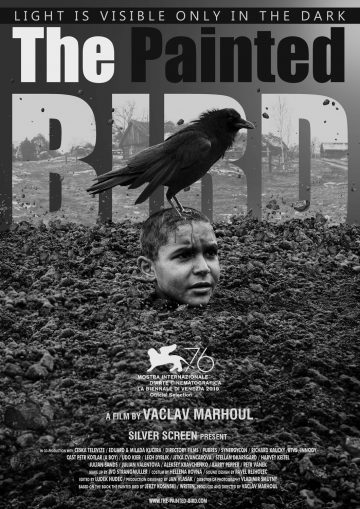

Arguably the most controversial film of 2019 (and also 2020, when it debuted in much of the world), this is a near-three hour adaptation of the iconic 1965 novel THE PAINTED BIRD by the late Jerzy Kosinski (whose name, to the filmmakers’ credit, comes first in the end credits). The film was an eleven year labor of love by writer-director Václav Marhoul, who managed to render Kosinski’s gruesome and unforgiving text in prestige movie fashion (it’s currently ranked as the 7th most expensive Czech film ever made), and with a cast that included a number of respected performers (Udo Kier, Harvey Keitel, Stellan Skarsgård, Julian Sands, Barry Pepper). Nobody involved appears to have been aware that during his life Kosinski was adamant that his novel not be adapted for film.

Arguably the most controversial film of 2019 (and also 2020, when it debuted in much of the world), this is a near-three hour adaptation of the iconic 1965 novel THE PAINTED BIRD by the late Jerzy Kosinski (whose name, to the filmmakers’ credit, comes first in the end credits). The film was an eleven year labor of love by writer-director Václav Marhoul, who managed to render Kosinski’s gruesome and unforgiving text in prestige movie fashion (it’s currently ranked as the 7th most expensive Czech film ever made), and with a cast that included a number of respected performers (Udo Kier, Harvey Keitel, Stellan Skarsgård, Julian Sands, Barry Pepper). Nobody involved appears to have been aware that during his life Kosinski was adamant that his novel not be adapted for film.

The novel, about a young boy’s wanderings through an unidentified Eastern European landscape during WWII, both made and destroyed Jerzy Kosinski’s reputation. Its infernal brilliance was fully recognized upon its publication, and it was the cornerstone upon which Kosinski, a New York based Polish immigrant, built his fame—but things looked quite bad when it was revealed in 1982 that the novel was actually put together by a fleet of uncredited translators and editors, and contained a great deal of plagiarized content. The revelation led, many believe, to Kosinski’s 1991 suicide at age 57.

The film is the first to be presented in the Interslavic language (because, according to Marhoul, “I didn’t want some nation to be associated with” the awfulness it depicts). It’s barely a year old as I write this, but has already garnered an impressive amount of controversy, having apparently caused mass walk-outs during festival screenings and faced widespread criticism for its extreme violence.

The opening scene, in which the boy in question (Petr Kotlár), here named Joska, has his pet ferret doused with oil and burned to death, adequately sets the tone. Joska, we learn, has been separated from his Jewish parents and left to stay with his elderly aunt in her country home, located somewhere in Eastern Europe during WWII. Inevitably the old woman dies one day, and Joska accidentally burns down her house.

From there he wanders from one gruesome situation to the next. Literally everyone Joska meets—superstitious peasants, corrupt priests, sadistic educators and trigger-happy military men (allied and otherwise)—is corrupt, ignorant, depraved or all three, leading to abuse of every conceivable stripe. To whit: Joska is beaten, buried up to his neck in dirt, dragged behind a horse-drawn carriage and forced to contend with a vicious dog. After an especially traumatic incident that concludes with the boy being tossed into a manure pit by an angry mob he loses his ability to speak.

Joska initially tries to do good (as when he gives the eyeballs of a man who’s just had them gouged out back to him), but after being spurned by a randy young woman he allows his baser instincts to take over, resorting to murder, thievery and hanging out with a deranged Russian soldier. The boy is eventually reunited with his long-lost father (who’s just been liberated from a concentration camp), but the relationship is a strained one.

All of this is depicted in beautifully lit and composed black and white imagery, courtesy of cinematographer Vladimír Smutný, who claims the intent was to replicate the look of black and white WWII photos. Smutný’s work goes well with the stately pacing and handsome art direction, courtesy of production designer Jan Vlasák. Whatever else this film may be, it’s certainly among the most sumptuously mounted collection of horrors ever committed to cinema.

Obviously a full rendering of the Kosinski novel’s outrages, which include rape, bestiality, pedophilia, sadomasochism, mutilation and dismemberment (and that’s only a partial list), would be inadvisable, if not impossible, to transpose to the screen. For those familiar with Kosinski’s text a large part of the film’s interest is in what portions Marhoul chose to include; a passage in which Joska is molested by a seductress known as Stupid Ludmilla is omitted, for instance, but Marhoul and his collaborators apparently had no trouble dramatizing the following one, in which Ludmilla is killed by having a bottle jammed up her vagina.

In truth Marhoul handles the mayhem about as “tastefully” as possible, with most of the nastier bits (including the aforementioned eyeball gouging and bottle rape) occurring off-screen, although more disturbing than the violence itself is the nonchalant air with which it’s presented. Commonplace drama and sentimentality have been completely expunged from this film’s universe, where unspeakable acts occur without dramatic music cues or tonal changes. In this sense the film is very much in sync with the novel, which took a similarly unimpressed view of its characters’ doings.

Ultimately THE PAINTED BIRD is unique among WWII set films, as it’s not a black comedy (a la the similarly themed EUROPA EUROPA), nor a historical saga (a la COME AND SEE), nor a hallucinatory drama (a la DIAMONDS OF THE NIGHT). Rather, this film’s only real point of comparison is to its own gruesome, unsparing and ultimately quite brilliant self.

Vital Statistics

THE PAINTED BIRD (NABARVENE PTACE)

PubRes/Silver Screen/IFC Films

Director: Václav Marhoul

Producers: Aleksandr Kushaev, Václav Marhoul

Screenplay: Václav Marhoul

(Based on a novel by Jerzy Kosinski)

Cinematography: Vladimír Smutný

Editing: Ludek Hudec

Cast: Petr Kotlár, Nina Shunevych, Alla Sokolova, Udi Kier, Michaela Dolezalová, Zdenek Pecha, Lech Dyblik, Jitka Cvancarová, Stellan Skarsgård, Harvey Keitel, Julian Sands, Julia Valentova Vidrnakova, Aleksey Kravchenko, Barry Pepper, Petr Vanek