One of the few films I can confidently assert will “shock the unshockable.” THE CHEKIST is a blistering look at an executioner going about his work in the wake of the Russian Revolution that’s guaranteed to traumatize the most hardened viewers.

One of the few films I can confidently assert will “shock the unshockable.” THE CHEKIST is a blistering look at an executioner going about his work in the wake of the Russian Revolution that’s guaranteed to traumatize the most hardened viewers.

THE CHEKIST (TCHEKIST) thus far hasn’t received the attention it should have. It was made in the former Soviet Union in the early days of Glasnost—needless to say, it could NOT have been made before then. Its graphic and unforgiving approach was an incredibly audacious choice, before or after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Set in 1917, the year of the Russian revolution, THE CHEKIST concerns itself with the Bolshevik Secret Police, or C.H.E.K.A., the forerunners of the KGB, whose job it was to round up and deal with those opposed to communist principles. Inevitably, the Cheka “dealt” with the latter via cold-blooded execution (foreshadowing the Stalinist purges of the coming years), something this film makes horrifically clear.

Interestingly enough, it was released in 1992, the same year as Andrei Konchalovsky’s THE INNER CIRCLE, another work by a Russian filmmaker casting a critical eye on his country’s none-too-distant past. A big-budgeted Hollywood production with American actors speaking in fake Russian accents, THE INNER CIRCLE makes for a fascinating contrast with THE CHEKIST, in whose shadow Konchalovsy’s film plays like a Disney cartoon. Quite simply, there aren’t too many other films of any type as unforgiving as THE CHECKIST, and it deserves a much wider audience than it’s received thus far.

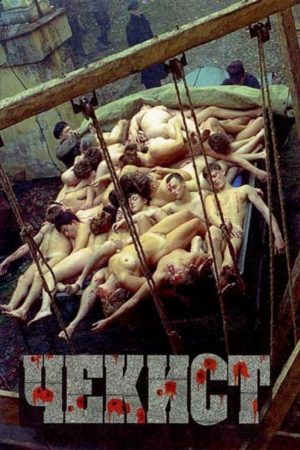

In the early days of the Russian Revolution a secret police force called Cheka is instigated to round up and snuff out any and all opposition to the new communist rule, including Jews, Christians, aristocrats and friends and relatives of the above. Cheka officer Andrei Srubov and his men decide to take their captives into the dank basement of their building and, against a wall lined with old doors, shoot them in the backs of their heads. The bodies are then loaded onto a rolling cart and wheeled to the bottom of a hole; next, men waiting above lower down a noose that is used to haul the corpses above ground, where they’re shipped off to mass graves.

Thus a routine is established that continues over a lengthy period, with Srubov and his men dispassionately executing hundreds of people. Srubov takes his job seriously enough that he stops one of his subordinates from raping an intended victim (“what’s the difference?” the guy asks, “she’s going to die anyway”), yet his conscience does bother him…and, as the executions continue, his fellow Chekists begin cracking up: one tries to hang himself and another senselessly bayonets a woman. Eventually Srubov goes mad himself, stripping off his clothes and, during one of the executions, running directly into the line of fire.

What makes this film especially potent is the matter-of-fact manner its protagonists go about their grisly duties. Director Alexandr Rogozhkin doesn’t embellish or sensationalize the film’s countless executions in any way, which makes them all the more unnerving to watch. Rogozhkin is less effective in presenting the characters’ lives outside the killing chamber, where they tend to speak in political slogans rather than dialogue. The film is at its most potent in scenes of undiluted horror, and the way Rogozhkin presents the grotesquerie is intriguing, beginning with cutaways and then gradually adding detail until, by mid-film, the shootings are graphically and relentlessly portrayed in a near-montage of remorseless slaughter.

Again, the killings are rendered especially effective in the way Rogozhkin steadfastly refuses to succumb to the lure of melodrama. His characters aren’t presented as psychopathic killers but as workers—some politically motivated, some not—going about their business, and we see them joking around and dealing with the myriad problems (the doors behind the victims becoming brittle from too many gunshots, the executioners’ aim being off, etc.) that come up just as workers would in any job.

This may make the film sound cold-blooded, but I’d argue the opposite. What Rogozhkin is above all else is honest, and brutally so, about the period he depicts, and I can’t imagine any viewer being unmoved by what he/she sees. THE CHEKIST is likely the most potent denunciation of communism ever made, particularly when one considers that the many hideous scenes it presents are but a microscopic glimpse of what actually occurred.

Vital Statistics

THE CHEKIST (TCHEKIST)

Lenfilm Associates/Trinity Bridge Productions

Director: Alexandr Rogozhkin

Screenplay: Jacques Baynac, Andre Milbet

Cinematography: Valeri Myulgaut

Editing: Tamara Denisova

Cast: Igor Sergeyev, Aleksei Poluyan, Mikhail Vasserbaum, Sergei Isavnin, Vasili Domrachyov, Aleksandr Medvedev, Aleksandr Kharashkevich, Igor Golovin, Nina Usatova