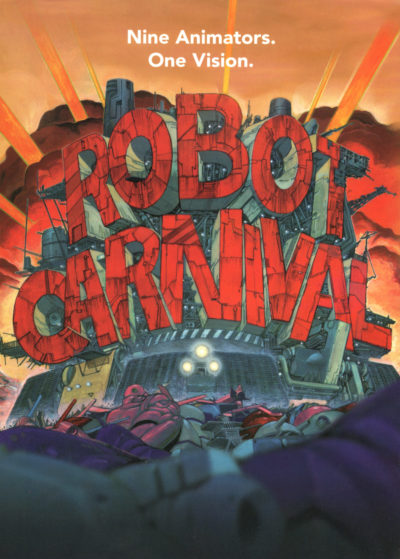

In the category of films that should have gotten a much grander reception than they did, ROBOT CARNIVAL looms large. An extremely ambitious production, it was nothing less than 1980s-era Japan’s answer to FANTASIA (1940), a highly artistic compilation of (mostly) wordless imagery in the form of eight animated segments, each created by one of Japan’s top animators, involving robots.

In the category of films that should have gotten a much grander reception than they did, ROBOT CARNIVAL looms large. An extremely ambitious production, it was nothing less than 1980s-era Japan’s answer to FANTASIA (1940), a highly artistic compilation of (mostly) wordless imagery in the form of eight animated segments, each created by one of Japan’s top animators, involving robots.

Japan’s answer to FANTASIA (1940)

The film was initially released in 1987 but took until 1991 to make its way to the US (courtesy of Steamline Pictures). By that point one of its creators, Katsuhiro Ôtomo, had wowed the world with AKIRA in 1988, and so served as the “star” contributor.

Ôtomo’s segment (co-directed by Atsuko Fukushima) opens the film with an APOCALYPSE NOW inspired bit of wonton destruction in which a firepower equipped “Robot Carnival” (as is written in English) barge invades a desert community, laying waste to everything in sight. It’s hard to discern whether Ôtomo and Fukushima are decrying the mayhem or reveling in it, but the visual bravura on display is undeniable.

…a highly artistic compilation of (mostly) wordless imagery in the form of eight animated segments, each created by one of Japan’s top animators, involving robots.

It’s followed (in the theatrical version, although for some reason not the VHS and DVD releases) by “Franken’s Gears,” written and directed by Kouji Morimoto. It’s a visually dazzling (if conceptually limited) FRENKENSTEIN-inspired depiction of a mad scientist creating a robot that upon coming to life wrecks the laboratory in which it and its creator are housed. Ethereal spot lit illumination is a constant.

“Starlight Angel,” from Hiroyuki Kitazume, contains everything we’ve come to expect from traditional sci fi anime: a doe-eyed young woman being rescued from the clutches of a robotic monster by a young man who’s every bit as pretty as she, all occurring in and around an amusement park at night (where Akira and Tetsuo from AKIRA also appear). The music, at least, is strong.

“Cloud” by Mao Lamdo (a.k.a. Manabu Ôhashi) is the most self-consciously “artistic” segment. Rendered in highly impressionistic black and white drawings, it depicts a cute robot boy traversing a wind-swept cloud-scape in which said clouds take the form of various animals and an atomic bomb, until a young woman angel becomes enraptured with the robot boy and transforms him into a human. An eccentric take on PINOCCHIO? A metaphoric depiction of Japan in the 20th Century? An excuse for some excess artiness? Your guess is as good as mine.

The chaotic “Deprive” by Hidetoshi Ômori (who worked as an animator on the XXX-rated UROTSUKIDOJI series) offers another run-through of traditional anime tropes, with another young woman getting kidnapped by an evil robot, and another heroic young man saving the day.

“Presence” by Yasuomi Umetsu (a key animator on GRAVE OF THE FIREFLIES) is a lyrical Ray Bradbury-esque narrative involving a refined inventor and a robot woman that haunts him. It’s admirably ambitious, but suffers from an overly self-conscious treatment, and glacial pacing that makes it difficult if not impossible for the viewer to maintain attention.

“A Tale of Two Robots” by Hiroyuki Kitakubo (who would go on to helm BLOOD: THE LAST VAMPIRE) is a comedic narrative involving two massive robotic constructs battling each other in the 17th Century. One is manned by an evil scumbag who’s looking to destroy Japan and who (crucially) speaks English, and the other, less high-tech one is run by a band of plucky youngsters who constantly bicker. I wouldn’t dream of revealing who wins.

“Nightmare” by Takashi Nakamura is ROBOT CARNIVAL’S answer to FANTASIA’S “Night on Bald Mountain.” The setting is an above-ground industrial hellscape lorded over by a robotic monstrosity and an army of mechanical demons amid ever-present smoke and flame, while in the city below a drifter is pursued by one of the creature’s minions, a beady-eyed, black-coat wearing creep. The dark and evocative score (inspired, allegedly, by Jerry Goldsmith’s music for the George Miller segment of TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE) is the segment’s major selling point.

The film concludes with the Robot Carnival barge from the opening scenes literally falling apart upon hitting an impassable mound. Yet it has a final outrage in store, involving a robot figurine that when unveiled in an impoverished family’s shack blows both the shack and its inhabitants sky high.

Taken as a whole, ROBOT CARNIVAL is not the masterpiece its creators intended, but it is striking. At its best—represented IMO by the intro and outro segments, “Franken’s Gears” and “Nightmare”—the film is gripping and eye-pleasing. Its segments, furthermore, are (in the original theatrical version) quite effectively ordered.

…not the masterpiece its creators intended, but it is striking.

The film’s greatest failing is that it never transcends the traditional anime model–indeed, in “Starlight Angel” and “presence” it bolsters that model. Thus it can never hope to approach, much less surpass, FANTASIA (or even ALLEGRO NON TROPPO).

Vital Statistics

ROBOT CARNIVAL

A.P.P.P./ 4°C/Steamline Pictures

Directors: Katsuhiro Ôtomo, Atsuko Fukushima, Kouji Morimoto, Hiroyuki Kitazume, Manabu Ôhashi, Yasuomi Umetsu, Takashi Nakamura, Hiroyuki Kitakubo

Producer: Carl Macek

Screenplay: Hiroyuki Kitakubo, Hiroyuki Kitazume, Kôji Morimoto, Takashi Nakamura, Yasuomi Umetsu, Manabu Ôhashi, Hidetoshi Ômori, Katsuhiro Ôtomo

Cinematography: Toshiaki Morita

Editing: Yukiko Ito, Harutoshi Ogata, Osamu Toyosaki

Cast: Kôji Moritsugu, Yayoi Maki, Keiko Hanagata, Kumiko Takizawa, Aya Murata, Nariko Fujieda, Satoru Inagaki, Hideyuki Umezu, Ikuya Sawaki, Hidehiro Kikuchi, Daisuke Namikawa, Tatsuhiko Nakamura, Kei Tomiyama, Chisa Yokoyama, Katsue Miwa, Kaneto Shiozawa, Toku Nishio, James R. Bowers