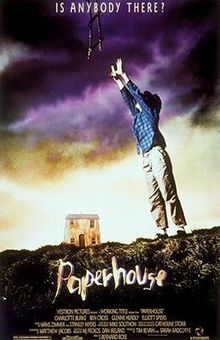

This brilliant but criminally neglected horror-fantasy is long overdue for a rediscovery. In an increasingly rare development, PAPERHOUSE spins a gripping, consistently surprising narrative, and, even rarer, does so with a great deal of originality.

PAPERHOUSE (1988) Trailer

PAPERHOUSE, a modestly budgeted British production from 1988, was adapted from the young adult novel MARIANNE DREAMS by Catherine Storr. The film was the well-received (by the lucky few who got a chance to see it) feature debut of director Bernard Rose, and in many ways set the tone for what was to come from this staunchly idiosyncratic filmmaker, who’s best known for the successful Clive Barker adaptation CANDYMAN.

PAPERHOUSE also foreshadowed the distribution problems many of Rose’s subsequent films would undergo in its truncated theatrical release by the short-lived Vestron Films. Later Rose projects include the true crime drama CHICAGO JOE AND THE SHOWGIRL (1990), which was barely released, ANNA KARENINA (1997), which was recut by its distributors, and the acclaimed IVANSXTC (2000), which like PAPERHOUSE was given extremely limited distribution.

In PAPERHOUSE the 11-year-old Anna is coming down with something—she suffers from fainting spells during which she dreams of a foreboding house situated in the midst of an oddly deserted plain. Anna comes to realize that the strange abode of her dreams is directly inspired by a drawing she made earlier. She makes some additions to the drawing, most notably a glum-faced boy in one of the house’s upper windows. Lo and behold, the next time Anna approaches the house in her dreams she finds a boy staring out that very window. He can’t move, though, as he’s paralyzed from the waist down.

Turns out the boy, named Mark, is real. He’s currently interred in a hospital located near the apartment where Anna lives with her aloof photographer mother and largely absent father. Anna decides it’s up to her to save the ailing Mark in her dreams, which for some reason Mark shares. Anna makes a mistake, though, in introducing her father into the dream world, as her subconscious renders him as a dark, eyeless brute who only makes Mark’s problems worse.

Mark it seems is going to die, and Anna has no way of helping him. Nor is she too easy on herself, as the more time she spends in her dream world, the more her physical body suffers, slipping into fever and delirium to the point where she no longer has to dream in order to contact Mark in the forbidding house!

Although his filmography is wildly uneven, Bernard Rose is an uncommonly gifted moviemaker. That’s fully evident in PAPERHOUSE, which has a smooth, confident flow and uniformly solid performances. The American Glenne Headly, speaking with a convincing British accent, is quite good as the lead character’s mother, and Charlotte Burke extremely winning as the winsome Anna. The latter is not the type of wide-eyed innocent favored by Hollywood, but a conflicted young woman who’s often bratty and self-centered–in other words, a girl who could have been snatched directly out of the real world.

Rose also demonstrates evident skill in his presentation of Anna’s dream world, done with an unshowy surrealism and a subtly unnerving aura of creeping menace. The film is mercifully free of gratuitous gore or cheap scares, and concludes with an exhilarating epic flourish that remains virtually unique in modern genre cinema.

What ultimately distinguishes PAPERHOUSE, however, is its narrative prowess. As arrestingly odd as it is, it’s the old-fashioned storytelling that seduces viewers, and which lingers long after the film is over. The tale has the elemental power of a campfire tale, and contains all the virtues of such an account, being scary, suspenseful and consistently unpredictable.

Vital Statistics

PAPERHOUSE

Vestron Pictures

Director: Bernard Rose

Producer: Tim Bevan, Sarah Radclyffe

Screenplay: Matthew Jacobs

(Based on a novel by Catherine Storr)

Cinematography: Mike Southon

Editing: Dan Rae

Cast: Glenne Headly, Charlotte Burke, Ben Cross, Elliott Spiers, Jane Bertish, Samantha Cahill, Sarah Newblood, Gary Bleasdale, Gemma Jones, Steve O’Donnell, Karen Gledhill, Barbara Keogh