The magnum opus of Japanese animator Keita Kurosaka, a 55-minute phantasmagoria offering further proof that any film with a heroine named Midori is well worth the attention of all weird movie buffs. Known for abstract Lynchian shorts like SEAR ROAR (UMI NO UTA; 1988), PERSONAL CITY (KOJIN TOSHI; 1990) and BOX AGE (HAKO NO JIDAI; 1992), Kurosaka’s bizarre aesthetic was furthered by MIDORI-KO (2010), which as with many weird movie classics (ERASERHEAD, LITTLE OTIK, etc.) is centered on child-rearing.

MIDORI-KO Trailer

The opening scenes are conveyed via childlike still pictures, accompanied by narration. We learn that a little girl named Midori hates meat because she feels sorry for the animals that died to create it, and wishes to be transported to the “Land of Vegetables.”

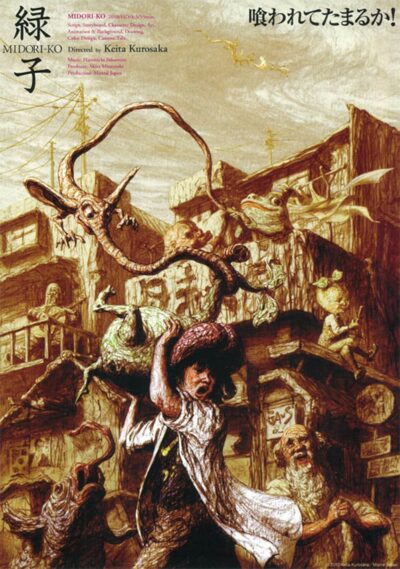

At this point we’re introduced to the film’s true animation style, consisting of vaguely humanlike figures making their way through a deliberately sketchy black-and-white landscape with surface textures that flow and shift. In this universe, which would appear to be intended as a dream or hallucination experienced by Midori, objects and people are subject to constant mutation.

Midori, one of the sole fully human-looking characters to be found, collects mutant vegetables while living in a boarding house that appears straight out of the nineteenth century (albeit with a computer), peopled with pumpkin and banana headed children and talking fish. Midori spends her days selling her vegetable finds at a roadside stand, where she gets robbed more often than not.

One particular veggie, which initially takes the form of a blob-like critter that crashes through Midori’s glass ceiling, has what looks like a man’s face. As the days advance the plant becomes increasingly human-like, and Midori takes to bathing, burping and protecting it from predators both human(ish) and otherwise. One day, however, she accidentally sits on and flattens the baby plant, which turns out to have physical properties equivalent to a whoopee cushion, meaning it can be blown up and makes fart sounds when deflated.

As the plant person grows it becomes quite mischievous and has to be put in a cage. It breaks out, however, and gets devoured by a frog man, only to be vomited out in an impossibly massive form that all the townspersons enthusiastically devour. “Get your butts out of here!” Midori implores them, but to no avail.

All this is punctuated with miscellaneous mutilations, transformations and strange creatures that Kurosaka (whose interest in sequential narrative is admittedly limited) included seemingly on a whim. Such an overabundance of matter-of-fact lunacy leads to a problem that’s quite standard with weird animation, in that the setting is so overtly fantastic and irrational, the surreality of the core narrative makes little impression—meaning a plant baby doesn’t feel at all out of place.

Yet the visuals, drawn and animated by Kurosaka, have an undeniably gorgeous sheen, resembling classic paintings brought to life. Movement was limited by the non-budget with which Kurosaka had to make do, but the artfulness of the enterprise helps forgive the paltry resources.

As with other contemporary weird animation specialists like Jan Svankmajer and the Quay brothers, Kurosaka places great importance on sound. In MIDORI-KO’s universe ambient sound is muted and music used sparingly, with bangs, stomps and thumps registering most strongly. Credit goes to sound effects creator Naoto Iwano and mixer Yoshihisa Omata, in addition to Kurosaka, who with this film proved himself a true master of cinema du bizarre.

Vital Statistics

MIDORI-KO

Mistral Japan

Director/Screenplay/Cinematography/Editing: Keita Kurosaka

Producer: Akira Mizuyoshi

Cast: Sayaka Suzuki, Rina Yuki, Chicapan, Miwako Mishima, Asuka Amane, Fumihide Kimura, Hiroyuki Kawai, Manta Yamamoto