A surreal gem from 1972, finally unearthed after years of obscurity in a newly restored director’s cut. Director Harry Kumel doesn’t entirely do his outsized ambitions justice, but MALPERTUIS (which roughly translates as “House of the Devil”) is a near-classic with a style, attitude and narrative arc that are entirely its own.

MALPERTUIS started life as an acclaimed 1943 novel written in French by the famed Belgian fantasist Jean Ray (1887-1964). An English edition didn’t appear until 1998, and it, like the film adaptation under review, has since become fairly obscure. Nevertheless I highly recommend the book, being a rich, complex epic of horror filled with mystery and weirdness. Told through multiple narrative strands, copious flashbacks and innumerable subplots, it relates the macabre tale of the forbidding abode Malpertuis and its eccentric inhabitants, all of whom share an unearthly secret.

In adapting this bizarre work Belgian filmmaker Harry Kumel (following up the international hit DAUGHTERS OF DARKNESS), together with screenwriter Jean Ferry, pared Ray’s multi-pronged narrative down considerably. Only a portion of the book ultimately made its way to the screen, with subplots involving a globe-trotting sorcerer, an accursed island, a werewolf and an inquisitive monk all excised.

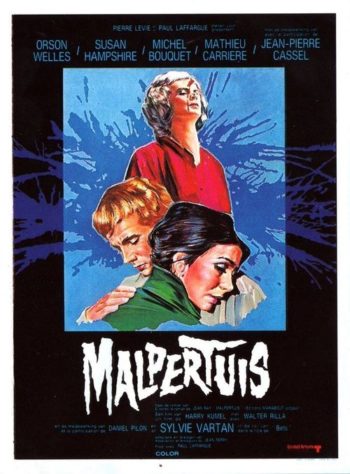

The film, featuring top-notch European actors like Michel Bouquet, Susan Hampshire (playing three separate roles) and Jean-Pierre Cassel, along with Orson Welles, was partially financed by United Artists and granted the highest budget ever accorded a Belgian film. Alas, it was not a success, with a heavily reedited and rescored 100-minute cut prepared for the 1972 Cannes Film Festival without Kumel’s input (the original cut reportedly ran 124 minutes). For years the Cannes version was the only available version of MALPERTUIS; it wasn’t until mid-2007, with the release of Barrel Entertainment’s DVD set (which is now out of print, sadly), that the film was at last allowed to be seen in its intended version.

Jan, a naïve sailor, disembarks one day in the town where he grew up. Depressed after finding that his childhood home is under new ownership, he’s drawn into dark, labyrinthine streets, ending up in a raucous bar where he’s nearly beaten to death. Jan’s been followed by two mysterious figures, who haul his unconscious form aboard a schooner bound for an accursed mansion called Malpertuis.

At Malpertuis several eccentric people are currently ensconced, including the sinister Euryale; the airy harp player Matthias; the seductive Alice; the staunch and pragmatic Nancy, who happens to be Jan’s sister; the gaunt and dejected Lampernisse, who’s always screaming about “the light!”; and their dying Uncle Cassavius. Before kicking off Cassavius informs his relatives that as a condition of his will they’ll all have to stay in Malpertuis and never leave.

This it turns out is only the first of several mysteries confronting Jan. Before long Cassavius passes on and Euryale tells Jan she wants to marry him after everyone else dies. But then Alice starts coming on to him and the weirdness piles up: Jan discovers a tiny severed human arm caught in a rat trap, finds that Cassavius’ corpse has inexplicably turned to stone, stumbles upon Matthias with a spike through his head (to which Malpertuis’ other residents pay little heed), and sees an invisible something snuffing out the lights, much to Lampernisse’s dismay.

One night Jan is drawn away from Malpertuis by Alice. The citizens of the surrounding town are, appropriately enough, engaged in a vast costume party, and Jan uses the opportunity to flee the confines of Malpertuis–or at least try to! But Jan’s ultimate fate, it seems, is inexplicably tied up with those of his doomed family members, and the dark secret underlying everything.

In its restored form, this film is a dazzler. The visuals are bold and impressive, the color scheme eye-popping and the camerawork never less than attention grabbing, with many arrestingly off-kilter set-ups. Harry Kumel’s filmmaking is incredibly dense, which may not be immediately apparent on one’s initial viewing. Subsequent viewings reveal the amazing proliferation of elements Kumel and cinematographer Gerry Fisher worked in: The lighting has a tendency to change unexpectedly, often in a single shot, and the complex visual compositions subtly prefigure the mystery at the story’s center.

That mystery, steeped in mythology and divinity, is quite farfetched, and raises just as many questions as it answers. But there is a real disorienting logic to the film’s construction; even though it falls apart somewhat in the end (the concluding Lewis Carroll epitaph, “Life, What is it but a Dream?” seems a little too pat), it’s still an admirable achievement.

Please note that the above applies solely to the newly released 119-minute director’s cut, even though technically it’s a bit ratty. It suffers from inconsistencies in the quality of the film stock and contains quite a few scenes that conclude in freeze frames. This was apparently because it had to be reconstructed from the 100-minute Cannes version, which was all that remained of the original film. But this new cut is still the only one worth viewing, because even if it isn’t entirely definitive, it’s still the closest we’ll ever come.

Vital Statistics

MALPERTUIS (a.k.a. THE LEGEND OF DOOM HOUSE)

Sofidoc/Artemis Film/United Artists

Director: Harry Kumel

Producers: Paul Laffargue, Rita Laffargue

Screenplay: Jean Ferry

(Based on a novel by Jean Ray)

Cinematography: Gerry Fisher

Editing: Harry Kumel

Cast: Orson Welles, Matthieu Carriere, Susan Hampshire, Michel Bouquet, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Sylvie Vartan, Charles Janssens, Daniel Pilon, Dora van der Groen, Walter Rilla