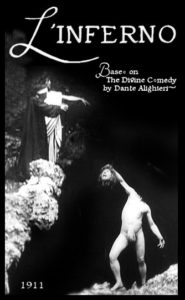

A truly astonishing restoration, this pioneering literary adaptation from 1911, long thought lost, was at last pieced together and exhibited in 2004. L’INFERNO is a fairly literal, if extremely broad, adaptation of Dante’s INFERNO with incredibly elaborate special effects. While quite primitive by today’s standards, this silent classic is still required viewing, if for no other reason than to experience the real origins of modern horror cinema.

L’INFERNO (1911) Full Film

L’INFERNO took over three years to make and was reportedly the first ever Italian feature film, and furthermore boasted the highest budget of its time. It reportedly took in over $20 million in the US alone, an astounding amount in the early days of cinema. Its international success wasn’t surprising, considering the widespread fascination Dante’s Fourteenth Century masterpiece THE DIVINE COMEDY, or at least the INFERNO portion, continues to exert. Notable modern permutations include Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s witty 1976 novel INFERNO and the postmodern spectacle A TV DANTE: THE INFERNO, co-directed by Peter Greenaway in 1992.

Incidentally, the 1911 film under discussion here is NOT the best known silent film version of Dante’s INFERNO. That honor goes to a 1912 remake by one of the earlier film’s three directors Giuseppe de Liguoro. The later film was apparently more elaborate and extensive clips from it were included in two subsequent films entitled DANTE’S INFERNO from 1924 and 1935, respectively, as well as Ken Russell’s ALTERED STATES. It is also credited in The Guinness Book of World Records as the first ever film to feature full frontal male nudity and, unlike the earlier version, appears to still be lost.

As in THE DIVINE COMEDY the poet Dante, on a stroll one day, finds himself lost in a dark and gloomy wood. He’s confronted by the “Hill of Salvation” which he endeavors to ascend, but is blocked by three avaricious animals representing different foibles of mankind. Luckily, the angel Beatrice (a young woman whose real-life death inspired Dante to pen his DIVINE COMEDY) descends from Paradise into Limbo and convinces the poet Virgil to guide Dante through the underworld.

After passing through a rocky portal adorned with the words “Abandon Hope all Ye Who Enter Here”, the poets approach the river Acheron, where the boatman Charon ferries the souls of the dead, those who in the “Great Rebellion” were “neither for God nor against Him, only themselves.”

From there they confront the chubby Judge Minos, who sits atop a rock and assigns punishment to each guilty soul. Around them swirl the carnal sinners, blown through the air by infernal gusts of wind (and whose ranks include Cleopatra and Helen of Troy). Next the poets enter the Circle of Gluttons, who lie on the ground tortured by eternal rain, guarded by Cerebus the three-headed monster. Virgil appeases Cerebus by throwing it a handful of earth and they continue on into the domain of the giant Pluto, who guards the misers and spendthrifts, who are condemned to roll great bags of gold around and around.

Next Dante and Virgil head for the City of Dis, the inner circle of the Inferno. The boatman Phleguyas ferries them across a river filled with tormented souls, but their entrance to the city of Dis is barred by a horde of evil spirits; three angels appear, however, to banish the spirits and grant the poets entrance. They subsequently pass through the swamp of the Styx, where souls overcome by anger are forever affixed, and the pits of fire where heretics are entombed. Dante and Virgil next approach the blasphemers, who suffer an eternal rain of fire (actually a few scattered fireballs).

Geryon, a creature with a man’s head and dragon’s body, carries the protagonists to the next circle of Hell. There they enter a forest of gnarled trees that are actually the souls of people who committed suicide. In a succeeding valley wastrels are chased around and lashed by demons, followed by the river of filth, where flatterers and dissolutes are immersed, attempting in vain to wash themselves clean. Then there are the summonists, who’ve sold the Church’s goods for profit, buried in the ground head downward and tortured by fire on the souls of their feet.

In the next circle, those who misappropriated the monies or properties of others are immersed in a river of boiling pitch, guarded by a bevy of vindictive demons who Virgil manages to placate. From there Virgil and Dante fly into the next circle, where they confront the hypocrites, condemned to walk around in heavy lead cloaks. In another valley are dozens of serpents which continually bite robbers—in the same location grafters and faithless custodians of public funds are transformed into ugly, reptilian critters. Fraudulent councilors and evil advisors are wrapped in flaming garments and the sowers of discord are continually maimed by demons. Forgers, falsifiers and counterfeiters are changed into lepers, left writhing on the ground.

Virgil gets the giant Antaeus, chained to a rock for his crimes, to lift up him and Dante and place them in final circle of hell, where traitors are immersed in a lake of ice. At the end of this circle is Lucifer himself, a gigantic winged dude gnawing on the bodies of Brutus and Cassius. The poets climb down the sides of Lucifer’s vast body and manage to exit Hell for good.

Cinematically you won’t find much to savor here, as the film was made long before the innovations of D.W. Griffith’s BIRTH OF A NATION. It’s composed entirely of wide shots that more often than not feature the two protagonists wandering around the edges of the frame while dozens of nearly naked folks (loincloths cover the genital areas) writhe in the center. Lengthy title cards fill us in on the action and dialogue before they happen.

Where the film distinguishes itself is in its rich and imaginative visual design, patterned after Gustave Dore’s illustrations for Dante’s work and shot on location in and around mountainsides, rivers and caves. The special effects certainly don’t measure up to those of today but retain their power to startle and intrigue; indeed, some of the optical work is quite ingenious in its use of forced perspective and superimposition. Particularly memorable effects include the sight of a guy holding his own severed head aloft (which chatters as if it were still affixed to his body) and the final shot of the devil joyously noshing on a flailing human body.

Another aspect of this restoration we’ll have to consider is the newly recorded score by Tangerine Dream, which has thus far proven quite controversial. TD here utilize uncharacteristically subtle tones in their score, which comes complete with English language vocals. The vocals are definitely an annoyance, but otherwise I found the score surprisingly effective; its dark, restrained ambiance actually makes for a haunting contrast to the hysteria of the visuals.

Vital Statistics

L’INFERNO

Eye Four Films Ltd. /Snapper Music

Directors: Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, Giuseppe de Liguorno

Based on THE DIVINE COMEDY by Dante Alighieri

Cast: Salvatore Anzelmo Papa, Arturo Pirovano, Giuseppe De Liguoro, Atilio Motta, Augusto Milla, Emilise Beretta