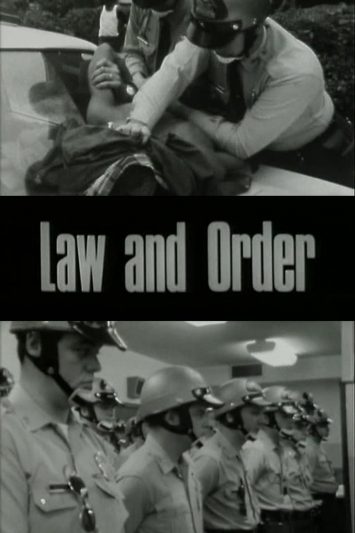

A documentary about police officers from 1969 that seems especially relevant to 2020. LAW AND ORDER is a classic of the Direct Cinema documentary movement (referring to the once-revolutionary practice of utilizing lightweight handheld cameras and live sound), and a signature film by the pioneering American documentarian Frederick Wiseman, who had already made the classics TITICUT FOLLIES (1967) and HIGH SCHOOL (1968). For LAW AND ORDER Wiseman travelled to Kansas City, where he spent a reported 400 hours accompanying policemen on various calls. The finished film, lensed in black and white, was broadcast in March, 1969 on the late National Educational Television (NAT) network, and won an Emmy Award for best news documentary.

A documentary about police officers from 1969 that seems especially relevant to 2020. LAW AND ORDER is a classic of the Direct Cinema documentary movement (referring to the once-revolutionary practice of utilizing lightweight handheld cameras and live sound), and a signature film by the pioneering American documentarian Frederick Wiseman, who had already made the classics TITICUT FOLLIES (1967) and HIGH SCHOOL (1968). For LAW AND ORDER Wiseman travelled to Kansas City, where he spent a reported 400 hours accompanying policemen on various calls. The finished film, lensed in black and white, was broadcast in March, 1969 on the late National Educational Television (NAT) network, and won an Emmy Award for best news documentary.

Playing nowadays like an especially blunt and unforgiving precursor to COPS, the film, in common with most Wiseman docs, contains no narration or narrative arc, nor any music or sound effects. We’re simply plunged into the action, with various policemen (no women) seen interviewing, lecturing and abusing people.

In one early scene a white cop helps a black woman find her stolen purse in a rare depiction of racial harmony. For the most part, though, the treatment of African Americans on display here is pretty ugly. We see a young black man held down by a cop’s hand pressed to his neck, a scene that obviously plays a lot differently now than it did in ‘69, and an even more disturbing bit in which a black woman is put in a choke hold by a burly white officer who dares her to “Go ahead, resist!”

We also see some white folks mistreated, most notably a middle aged man knocked to the ground when he attempts to walk away during an arrest, and a black cop coming to the aid of a woman being harassed by a cab driver–unusually for this movie, she thanks the officer for his help. In quieter scenes cops are admonished by a superior officer to not use degrading terminology when interviewing perps (“hoss,” “buddy,” “bub” and “hoosier” are the examples used, although he likely had another, more racially charged term in mind), and are seen casually chatting about their lives and profession, demonstrating Wiseman’s uncanny flair for capturing his subjects at their most natural and unguarded.

That talent is on further display in another Wiseman trademark: the cutaway shots, which are as important in their way as the foreground action. Noteworthy character-defining cutaways in LAW AND ORDER include a young woman tenderly nuzzling her infant child as her mom argues with a police officer and a young boy eagerly studying his reflection in the rearview mirror of a police car.

Overt politics are avoided until the final five minutes, when Richard Nixon is seen preaching about law and order at the 1968 Republican National Convention. Wiseman claimed he initially sought to “do in the pigs” with this film but had a change of heart, admitting “we liberals frequently forget that people do terrible violence to each other, against which the police form a minimal and not very successful barrier. I understand now the fear that cops live with.”

Part of the appeal of Wiseman’s 1960s films, from a modern perspective, is their time capsule fascination. LAW AND ORDER certainly has its share of late sixties time capsule elements—in the hilariously dated hairstyles, slang, etc.—but what’s ultimately most striking about the film’s depiction of policemen is how little has actually changed from then to now.

Vital Statistics

LAW AND ORDER

Osti Inc.

Director/Producer/Editor: Frederick Wiseman

Cinematography: Bill Brayne