The first of Roger Corman’s stately and refined Edgar Allan Poe adaptations. An affecting film, but I prefer my Corman pictures down and dirty.

The first of Roger Corman’s stately and refined Edgar Allan Poe adaptations. An affecting film, but I prefer my Corman pictures down and dirty.

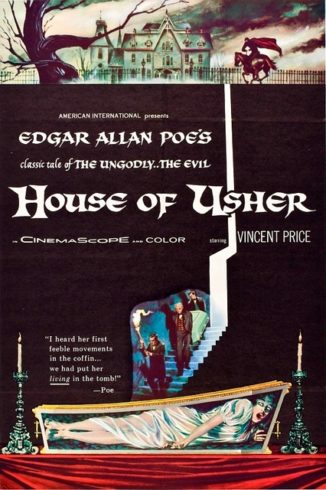

HOUSE OF USHER (1960) was the most expensive film yet made by the legendary exploitation outfit American International Pictures (its budget was $200,000!), run by James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff. It was also the first AIP picture to be released by itself (i.e. not on a double bill), and, according to its director Roger Corman, it single-handedly established AIP as a viable entity. Furthermore, Corman was given an unheard-of 15 day shooting schedule, as opposed to the standard 10 he was usually granted, and a cinemascope (2:35.1) aspect ratio.

Playing in “hard top” as opposed to drive-in theaters, HOUSE OF USHER was an enormous critical and financial success, and led to several more Corman directed Poe adaptations: THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM, PREMATURE BURIAL, TALES OF TERROR, THE RAVEN, THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH, and THE TOMB OF LIGEIA.

The mild-mannered Philip is set to marry Madeline Usher, who lives in a forbidding castle with her older brother Roderick. Philip arrives to find the surroundings looking ravaged and burnt out.

He meets Roderick, who’s immediately suspicious of Philip’s intentions. Roderick believes the Ushers are tainted by an ancient curse that has spread insanity through the succeeding generations; apparently the castle and its surroundings were once green and inviting, but, due to the effects of the apparent curse, are now withered and burnt-out. The castle itself seems complicit in Roderick’s claims in the way it appears to be literally cracking up.

But then one night Philip overhears an argument and a struggle between Madeline and Roderick issuing from the latter’s bedroom. Philip rushes in to find Madeline lying prone on the floor—dead, it seems.

Philip is present at a hastily held funeral for his beloved, and her subsequent interment in the basement of the castle (along with Madeline and Roderick’s ancestors). But Philip grows suspicious about Roderick’s claims regarding his ancestry…and the idea that Madeline is really dead. Could Roderick have interred her alive?

This film showcases Roger Corman, the master of fly-by-night low budget moviemaking, in restrained form. The proceedings are slow and talky, and set amidst an atmosphere of stately museum-like sets and artwork. Virtually the entire film was shot on sets rather than locations, which Corman claims was intentional, the idea being to create an enclosed subconscious state—the living house idea, BTW, was apparently added at the request of AIP co-chair Samuel Arkoff, who demanded a “monster.”

This brings us to the screenplay by Richard Matheson, which opens up Poe’s insular tale to include a love story, and largely jettisons the supernatural elements. Yet a hint of the poetry and strangeness of the original tale survives in Matheson’s surprisingly thoughtful, contemplative script. That’s also true of the lead performance by Vincent Price, who’s at his commanding best playing a character that’s both a monstrous villain and a tortured anti-hero.

The big shocks are saved for the end, which is easily the film’s finest sequence, a delirious mélange of blood, fire and lurid close-ups, all fully in line with the exploitation-happy Corman I know and love.

Vital Statistics

HOUSE OF USHER (a.k.a. THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER)

American International Pictures

Director: Roger Corman

Producer: Roger Corman

Screenplay: Richard Matheson

(Based on a story by Edgar Allan Poe)

Cinematography: Floyd Crosby

Editing: Anthony Carras

Cast: Vincent Price, Mark Damon, Myrna Fahey, Harry Ellerbe