A milestone in film history, and a requisite for any cult movie buff. FREAKS, a 1932 sideshow drama notable for featuring actual human oddities, isn’t especially polished or refined, but its deranged fascination and sheer uniqueness are undeniable.

A milestone in film history, and a requisite for any cult movie buff. FREAKS, a 1932 sideshow drama notable for featuring actual human oddities, isn’t especially polished or refined, but its deranged fascination and sheer uniqueness are undeniable.

Director Tod Browning (1880-1962), already something of a genre legend, had just scored an unexpected hit with DRACULA (1931), inspiring MGM’s Irving Thalberg to sign Browning to a multi-picture deal. That deal was set to begin with “Something Horrifying,” an adaptation of the 1923 story “Spurs” by Tod Robbins (and also, it would seem, the 1928 tale “The Children of Bondage” by Dagney Major, which contained many plot points replicated by FREAKS). The finished film allegedly caused viewers to run screaming from preview screenings and a pregnant woman to miscarry, and underwent heavy Thalberg-instituted editing, resulting in the 63 minute version (said to be around thirty minutes shy of its initial runtime) in which it currently exists.

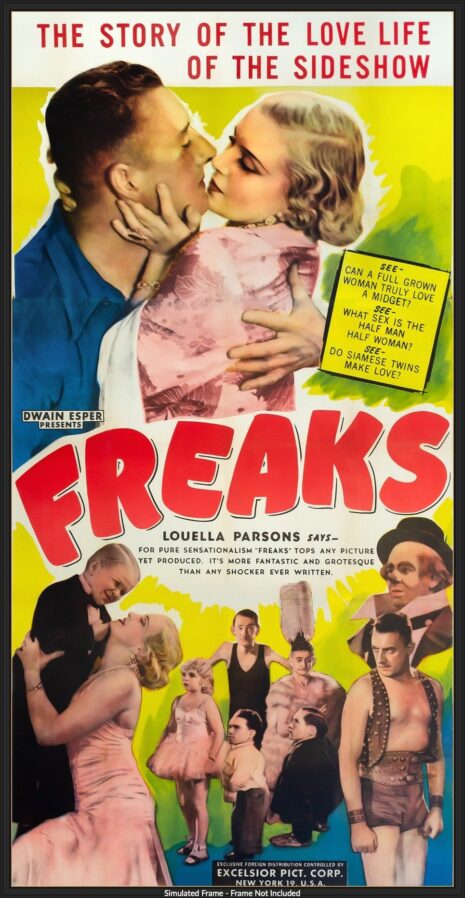

A massive flop, the film was disowned by MGM and banned in Britain. It was quickly purchased by the legendary sleazemeister Dwain Esper, who built up interest via roadshow distribution in the late 1930s and 40s (complete with a specially created textual prologue enumerating the historical basis for sideshows). FREAKS’s true coronation occurred at the 1962 Venice Film Festival, which brought it to the attention of film buffs the world over, and led to a dramatic critical turnabout; once dismissed as shameless exploitation, FREAKS now tends to be praised as thoughtful and compassionate cinema. Which viewpoint is correct? Let’s see.

The film opens with a sideshow barker at a traveling circus directing a gawking audience to “the most astounding living monstrosity of all time,” a former trapeze artist named Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova). As depicted in an extended flashback, Cleopatra was a sultry blonde lusted after by Hans (Harry Earles), a sideshow dwarf, and Hercules (Henry Victor), the circus strongman. She chooses the latter but agrees to marry Hans due to the fact that he’s set to receive a sizeable inheritance.

In the meantime we’re introduced to Hans’ fellow circus dwelling “freaks.” They include Half Boy (Johnny Eck), Human Skeleton (Peter Robinson), Armless Girl (Frances O’Connor), Half-man Half-woman (Josephine Joseph), Bearded Lady (Olga Roderick), Armless Girl (Frances O’Connor), Siamese Twins (Violet and Daisy Hilton), Living Torso (Prince Randian) and Hans’ dwarf fiancée Frieda (Harry Earles’s sister Daisy), who are seen fighting, hooking up and giving birth.

The Hans-Cleopatra marriage takes place off-screen, with the action picking up at the nighttime wedding party (signified by a silent movie-esque intertitle). Here, in the film’s most famous scene, the freaks try to initiate Cleopatra into their ranks via a ceremony that involves a fraternity cup being passed around and the chant “We accept her, one of us. We accept her, one of us. Gooble-gobble, gooble-gobble.” This only exacerbates the woman’s surly nature, resulting in a most undignified flip-out and the parading around of Hans jockey-like on Cleopatra’s back (an explicit nod to “Spurs,” whose primary motif was human horseback riding).

Cleopatra and Hercules plan to slowly poison Hans to death, with the first dose administered at the wedding party. As Hans grows progressively sicker his fellows take notice, and enact the “Code of the Freaks” during a rainstorm. Its then that Hercules attempts to kill Venus (Leila Hymans), one of the circus’ only sympathetic non-freaks, due to the fact that she knows about his plot against Hans. This sets in motion a melee that results in a violent death and the transformation of Cleopatra into the monstrosity of the opening scene.

Viewers will have to be accepting of the stilted performances of the non-actor title characters, and also the truncated nature of the film. Due to the unusually severe postproduction editing, the proceedings are rife with underdeveloped characters, unresolved subplots and scenes that tend to cut off before their logical conclusion, resulting in a lot of sudden fades to black and an ending that exists in three different forms, none of which are satisfying (or complete).

Yet there’s much to admire. The early scenes of offstage carnival life have an unforced naturalism (and are said to be the screen’s most authentic depiction of carny existence), while the storm-set climax, in which we’re shown misshapen knife-wielding figures crawling—nay, slithering-–through mud, is authentically terrifying.

Tonally the film is quite innovative, beginning as a comedy, morphing into a melodrama and concluding as a horrorfest. The title characters are presented as, variously, objects of ridicule (as when the suitors of a conjoined twin tells her sister’s fiancée that “You must come to see us sometime”), sympathetic outsiders and monstrosities of the type in which Tod Browning’s other films tended to specialize. Politically correct it isn’t, but FREAKS contains what is undoubtedly the most complex view of human oddities that exists in any film, meaning those 1930s-era critics who dismissed it as amoral exploitation and the later ones who praised its sympathetic portrayal are both right.

Vital Statistics

FREAKS

Metro Goldwyn Meyer

Director: Tod Browning

Producers: Tod Browning, Harry Rapf, Irving Thalberg

Screenplay: Willis Goldbeck, Leon Gordon

(“Suggested by” a short story by Tod Robbins)

Cinematography: Merritt B. Gerstad

Editing: Basil Wrangell

Cast: Olga Baclanova, Harry Earles, Daisy Earles, Henry Victor, Wallace Ford, Leila Hyams, Rose Dione, Daisy Hilton, Violet Hilton, Schlitze, Josephine Joseph, Johnny Eck, Frances O’Connor, Peter Robinson, Olga Roderick, Koo Koo, Prince Randian, Martha Morris, Elvira Snow, Johnny Lee Snow, Elizabeth Green, Angelo Rossitto, Edward Brophy, Matt McHugh