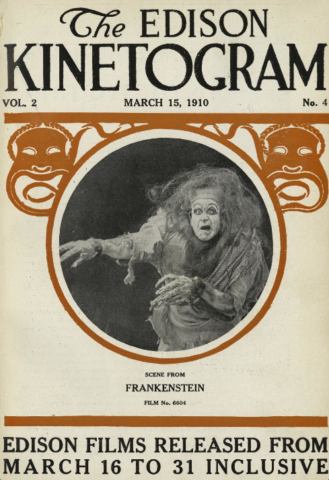

This is the holy grail of horror films, a one-reel silent adaptation of Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN made under the auspices of Thomas Edison back in 1910. Is it any good? Frankly, no. It is, however, required viewing for anyone with an interest in the evolution of horror cinema.

This is the holy grail of horror films, a one-reel silent adaptation of Mary Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN made under the auspices of Thomas Edison back in 1910. Is it any good? Frankly, no. It is, however, required viewing for anyone with an interest in the evolution of horror cinema.

The full story of this film’s making and reception can be found in the 2010 publication EDISON’S FRANKENSTEIN by Frederick C. Wiebel, Jr. While many of the details have been lost to history, Wiebel does an excellent job filling us in on the particulars of the film and its creators.

The actors in this FRANKENSTEIN all go unbilled (as was the custom at the time). They include Augustus Phillips, a regular in Edison films, as Dr. Frankenstein. Frankenstein’s monster was played by the tall and imposing Charles Ogle, another Edison mainstay who went on to become a prolific supporting player in countless silent films. Mary Fuller played Dr. Frankenstein’s sweetheart; she was one of the Edison Company’s biggest stars but never succeeded in making the transition to feature length films. The writer/director J. Searle Dawley was an innovator who pioneered many of the techniques modern filmmakers take for granted. All four, alas, have been largely forgotten and are now known solely for the film under discussion.

Regarding that film, it was evidently filmed and packaged like Edison’s other productions of the time: running just fifteen minutes, it was shot in three days at the Edison Studios in the Bronx, New York. It was the world’s first true horror film, although it wasn’t apparently advertised as such—the Edison Company doesn’t appear to have had any idea of what it put in motion!

This FRANKENSTEIN was believed lost for decades, and indeed might well have been were it not for one Alois Felix Detlaff, Sr., who acquired the only surviving print back in the 1950s. It’s that print, faded and decayed though it is, that now provides our sole glimpse of this vital piece of history.

The young Victor Frankenstein leaves his family home for college, and two years later discovers the “Mystery of Life.” Frankenstein writes his girlfriend to inform her that he’s about to use his skills to create the world’s first “Perfect Human Being,” after which he’ll return home and take her for his bride.

The none-too-Perfect being is created from chemicals in a vat in Frankenstein’s laboratory. Upon seeing his creation Frankenstein is horrified and retreats to his bedroom. But the creature, a tall, bushy-haired monstrosity with big feet and a mighty large forehead, peeks in on Frankenstein in his bed—and then abruptly disappears.

As promised, Frankenstein returns to his family home to propose to his sweetheart. The monster follows and, finding itself jealous of Frankenstein’s relationship with his bride-to-be, torments its creator incessantly.

Things come to head on Frankenstein’s wedding night. Frankenstein’s bride spots the monster in the living room and faints, after which Frankenstein succeeds in banishing the critter from the room. Back in Frankenstein’s bedroom the monster sees itself in a mirror and, apparently “Overcome by Love,” disappears.

To really comprehend this film one has to understand the limitations faced by moviemakers in 1910. Films back then rarely lasted over 15 minutes, which is about the length of this FRANKENSTEIN (although the surviving print is actually a couple minutes short). Being outgrowths of the stage, where the present director J. Searle Dawley got his training, films of 1910 were much like plays: close-ups were a no-no, with narratives presented in a succession of fixed-camera wide shots that began with someone entering from one side of the frame and concluding after they exited through the other, with textual intertitles delineating the particulars of the narrative. This explains what nowadays feels like a glaring omission: we never get a good look at Frankenstein’s monster, who is seen only in long shot.

There are some interesting elements herein. The special effects of the monster slowly forming before our eyes are beyond-primitive by today’s standards but were unprecedented for 1910. The use of mirrors is equally interesting, with the monster visible in several scenes solely through the door-sized looking glass in Frankenstein’s bedroom, suggesting the creature may be a refection of its creator’s own baser impulses.

The scene of Frankenstein’s monster looking in on its creator in his bed, taken directly from Mary Shelley’s original, is the only such scene in any FRANKENSTEIN movie and, together with the wedding night set climax, hints at the sexual panic of the novel. However, like so much else about this film, we’re left desiring more such hints–or at least a more fully rounded presentation of same.

Some background info on the story and characters might have helped matters. We never learn much—make that anything-–about what led Frankenstein to create his monster or precisely how he goes about doing so, nor the college he attends or the home he’s so eager to return to. For all we know, he pulled the spare body parts from his collection in a pods storage unit. Clearly Mary Shelley’s classic was not ideal material for a 15-minute film!

Ultimately, what you’ll see here are the seeds of something far greater. Virtually everything in this FRANKENSTEIN, from the special effects to the scare scenes to the histrionic performances to the disturbing sexual undertones, formed the basis of what we’ve come to recognize as horror cinema.

Vital Statistics

FRANKENSTEIN (a.k.a. EDISON’S FRANKENSTEIN)

Edison Studios

Director: J. Searle Dawley

Screenplay: J. Searle Dawley

(Based on the novel by Mary Shelley)

Cast: Augustus Phillips, Charles Ogle, Mary Fuller