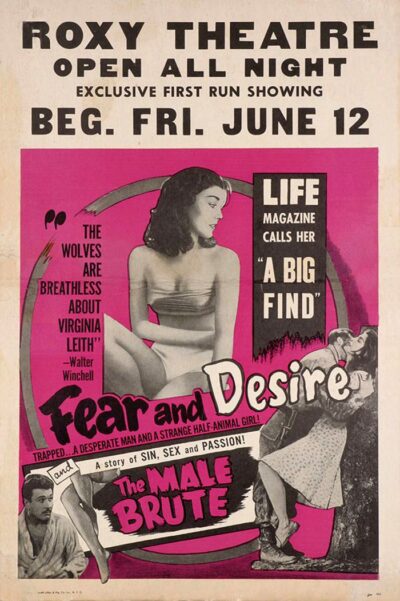

Yes, this was the 1953 feature debut of 22-year-old Stanley Kubrick, known at the time as a wunderkind still photographer for LOOK magazine. A precocious masterpiece (as some have tried to claim)? Nope. Worthless juvenilia (as many others, including Kubrick himself, maintain)? No, again. FEAR AND DESIRE is actually an interesting forerunner of things to come for a director who didn’t hit his filmmaking stride until his third feature (1956’s THE KILLING).

Scripted by future Pulitzer Prize winner (for 1967’s GREAT WHITE HOPE) Howard Sackler and filmed in the woodland bordering Los Angeles, FEAR AND DESIRE (initially titled THE SHAPE OF FEAR) followed the Kubrick directed shorts DAY OF THE FIGHT and FLYING PADRE (both 1951). Its final cost was around $50,000, bequeathed by Kubrick’s father and drugstore magnate uncle Martin Perveler. Lensed without sound (with dialogue and ambience dubbed in later), the film had a threadbare crew and an inexperienced cast that included future director Paul Mazursky (DOWN AND OUT IN BEVERLY HILLS), Virginia Leith (THE BRAIN THAT WOULDN’T DIE), Frank Silvera (THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD), Kenneth Harp (DIVORCE AMERICAN STYLE) and Stephen Coit (THE LONG GOODBYE).

Initially running 70 minutes, the film (anticipating the fate of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY) was shorn of 9 minutes by Kubrick after early audiences greeted it with laughter. In later years Kubrick sought to destroy the original negative (which, for the record, was unearthed in Puerto Rico in the nineties), and released this statement: “FEAR AND DESIRE was written by a failed poet, crewed by a few friends and is a completely inept oddity, boring and pretentious, a bumbling amateur film exercise.”

The subject is one Kubrick would return to multiple times: war. As a narrator (David Allen) intones over wide shots of an unidentified forest, “There is a war in this forest. Not a war that has been fought or one that will be, but any war. And the enemies who struggle here do not exist unless we call them into being. This forest, then, and all that happens now, is outside history.”

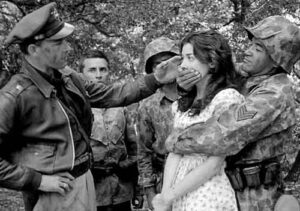

Four soldiers are left stranded in enemy territory by an unseen plane crash. Their ranks include the snarky Lieutenant Corby (Harp), the bulky Fletcher (Coit), the youthful Sidney (Mazursky) and the steely Mac (Silvera). A reconnaissance by the latter uncovers the existence of a riverfront house where several enemy combatants (played, in a surreal touch, by the same actors we’ve just seen) are stationed. Also discovered is a cabin in which two more soldiers are stationed, and, either to eliminate the enemy or simply to get at the food contained inside, our “heroes” massacre both men.

Later the quartet happen upon three beautiful women, one of whom (Leith) they capture and tie to a tree. Sidney is chosen to watch over the bound woman while his fellows head off. He intones, for some reason, passionate soliloquies from THE TEMPEST (the inception of Paul Mazursky’s interest in the play, which culminated in his 1982 filming of it) and nearly rapes the woman. She ends up escaping and getting shot by Sidney, who then goes completely mad.

His fellows, meanwhile, mount an attack on the riverfront house containing the enemy combatants. This leaves many corpses, including that of one of the protagonists, who’s stationed on a makeshift raft.

My verdict: the screen direction is nonexistent, the pacing wildly uneven, the lighting inconsistent, the staging clumsy and the dialogue hopelessly pretentious (“Sometimes, talk is an indispensable medicine”). The skilled music by Gerald Fried is about the only professional contribution, but it fails to hold things together.

There are interesting elements, such as the overlapping thoughts heard on the soundtrack in an early scene (“One foot fights the other,” “How much is in the back of us?,” “Don’t die here!”). There are also indelible images (gloppy stew slopping on the ground during the cabin massacre, a dead man’s feet displaced by a door, a pan across drooping trees bordering a river) that are impeccably lit and framed, evidencing Kubrick’s skills as a skill photographer while offering glimpses of his filmmaking genius.

Further foreshadowing is evident in the treatment of the lone female character, who as with most of the women cast members in future Kubrick films gets very little to do. And then there’s the depiction of Sidney’s insanity, which harkens forward to Kubrick psychopaths like Gen. Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) in DR. STRANGELOVE, Alex (Malcolm McDowell) in A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) in THE SHINING and Pvt. Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio) in FULL METAL JACKET.

Finally: FEAR AND DESIRE’s original 70 minute version, which was believed lost for many decades, is presented on the Kino Blu-ray together with the more common 61 minute cut-down. The former is said to be an interesting psychological study and the latter a more conventional war movie, but in my view both versions are equally interminable, with the 70 minute version merely being longer.

Vital Statistics

FEAR AND DESIRE

RCA

Director/Producer/Cinematography/Editing: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Howard Sackler

Cast: Frank Silvera, Kenneth Harp, Paul Mazursky, Stephen Coit, Virginia Leith, David Allen