In a 2007 BAFTA interview, David Lynch called ERASERHEAD (1977) his “most spiritual” film. “Elaborate on that,” the interviewer prompted, to which David Lynch replied “No, I won’t.”

ERASERHEAD, one of the world’s premiere examples of abstract filmmaking, was Lynch’s first feature. The production was a five year labor of love, filmed in and around the Beverly Hills based Doheny Mansion under the auspices of the American Film Institute, with Lynch delivering newspapers to fund it. The finished film, shepherded by midnight movie guru Ben Barenholtz, was Lynch’s most profitable, grossing $7.1 million against a reported $100,000 budget. It was not a little influential, with ATRAPADOS (1980), COMBAT SHOCK (1984), TALES FROM THE GIMLI HOSPITAL (1988), THE GROCER’S WIFE (1991), JO JO AT THE GATE OF LIONS (1992), ASHES AND FLAMES (1997), MIGRATING FORMS (1999), THE FLEW (2003) and ELEVATOR MOVIE (2004) being among the many, many films that have followed its lead.

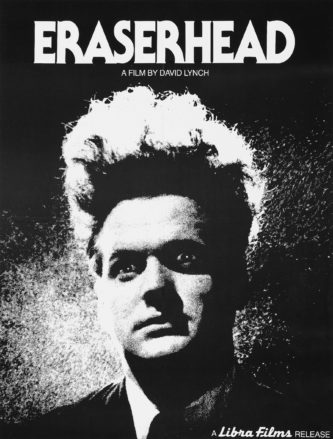

It opens with Henry (Jack Nance), a working stiff with hair arranged in a way that makes him resemble just what the title portends, opening his mouth and emitting a gruesome worm-like fetus, engineered by a deformed man (Jack Fisk) residing on a planet located inside Henry’s head. Not long after this, Henry learns that his girlfriend Mary (Charlotte Stewart) has given birth to a premature baby, as reported by her disapproving, and insane, mother (Jeanne Bates).

Cut to sometime later, when the baby, consisting of a severely mutated, animalistic head and a towel-wrapped body we never see (Lynch created the baby himself, but was fastidious about keeping the details secret, a secret he literally kept to his grave), resides on a table in Henry’s filthy apartment. The baby’s presence drives a wedge between Henry and Mary, who decides she can’t stand either of her companions. Henry for his part never seems entirely sure if Mary is present in the apartment or not.

In the meantime, he deals with illness, as experienced by the baby, who becomes covered in ugly sores, and Mary, who emits wormy secretions from her private parts, and the intrusions of a vixen (Judith Roberts) living across the hall. Salvation is offered by an angelic lady (Laurel Near) bearing ugly protuberances on both her cheeks, who in a stage inside Henry’s radiator lip synchs a song called “In Heaven Everything is Fine” (sung by Jack Fisk’s wife Sissy Spacek) and gleefully stomps on fetuses of a type seen in the opening scene. It’s she who awaits Henry after he quite gruesomely puts the baby out of its misery, accepting him into an indistinct heavenly realm (presumably the “spiritual” dimension specified by Lynch).

Viewers looking for clarity are in for a disappointment. The definitive ERASERHEAD analysis, “ERASERHEAD: AN APPRECIATION” by Kenneth George Godwin (contained in the 1984 issue of CINEFANTASTIQUE and reprinted in the 2020 book ERASERHEAD, THE DAVID LYNCH FILES: VOLUME ONE), views the baby as a penis and Henry’s major issue being thwarted desire, which seems authoritative enough, but the film’s primary allure is as (to quote Lynch himself) “a dream of dark and troubling things.”

ERASERHEAD is, in fact, the screen’s premiere example of dream logic, with a sense of artfully textured irrationality, punctuated with moments of comedy, which demonstrates the touch of a filmmaker who even at such an early stage of his career had already mastered his form. The low budget is belied by the assured visual design, and the lighting of cinematographers Herbert Cardwell and Frederick Elmes (who replaced Cardwell after a year’s work and collaborated with Lynch twice more) is simply some the finest, most expressive black and white photography that exists. Equally impressive is the sound recording and editing of Alan Splet, who imparts a tone-setting industrial drone that’s been imitated too often to catalogue but has never been duplicated (not even in Lynch’s subsequent films).

Yet as mind-bending as ERASERHEAD is, its real power lies in its spot-on depiction of real-life frissons. As with THE GRANDMOTHER (which gave voice to childhood fears), BLUE VELVET (in which the underside of picket fence America was laid bare) and LOST HIGHWAY (which probed marital anxiety), ERASERHEAD was rooted in reality, specifically the pressures of fatherhood, as experienced by a 21-year-old David Lynch trying to raise an infant daughter (future director Jennifer Lynch, who appears in ERASERHEAD) while attending art school in Philadelphia. The “realities” of that period may not show up onscreen, but its tensions and anxieties made it through unfiltered.

ERASERHEAD is certainly not for everybody, but if you’re one of those who (like me) is receptive to its ghoulish charms then my recommendation won’t mean much, as you’ve doubtless already viewed it at least a dozen times.

See more of Adam’s commentaries and reviews on David Lynch.

Vital Statistics

ERASERHEAD

Libra Films

Director/Producer/Screenplay/Editing: David Lynch

Cinematography: Herbert Cardwell, Frederick Elmes

Cast: Jack Nance, Charlotte Stewart, Allen Joseph, Jeanne Bates, Judith Roberts, Laurel Near, V. Phipps-Wilson, Jack Fisk, Jean Lange, Thomas Coulson, John Monez, Darwin Joston, “Neil Moran” (T. Max Graham), Hal Landon Jr., Jennifer Lynch, Brad Keeler