Perhaps the ultimate surreal film, though far from the best, an anthology feature with segments designed by the renowned surrealists Max Ernst, Fernand Leger, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and Alexander Calder, and directed by the avant-garde film specialist Hans Richter.

Perhaps the ultimate surreal film, though far from the best, an anthology feature with segments designed by the renowned surrealists Max Ernst, Fernand Leger, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and Alexander Calder, and directed by the avant-garde film specialist Hans Richter.

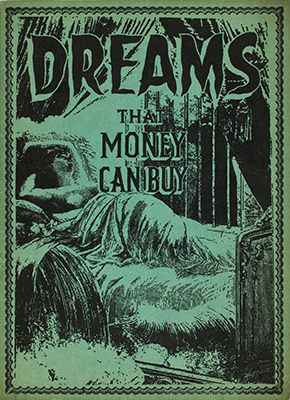

The German born, Dada affiliated Hans Richter made several avant-garde shorts throughout the 1920s and thirties, notably “Rhythmus 21” (1921), “Filmstudie” (1926) and the fantastic “Ghosts for Breakfast” (1927). The 1947 DREAMS THAT MONEY CAN BUY was made for $25,000 in a NYC loft in collaboration with several of Richter’s surrealist pals. It was given a generous spread in Life Magazine and won a special prize at the Venice Film Festival.

Surrealism began in Paris of the 1920s as a subversive art coalition, but by the late 1940s had become heavily commercialized and diluted, essentially a parody of itself. DREAMS THAT MONEY CAN BUY can be viewed as either the last hurrah or final nail in the coffin of this once-vital movement.

Joe, a “self-appointed bum,” discovers he can “look inside himself” (so insists an unseen narrator) and comes up with a novel money making scheme: selling dreams in his big city apartment to those who have none.

Case #1 is “Mr. A,” a boring art-obsessed Asian man who Joe bequeaths a Max Ernst designed dream involving a sleeping woman who devours a floating ball and several people who emerge from a misty expanse under her bed.

Case #2 is a woman suffering from “Organizational Neurosis.” Her dream, courtesy of Fernand Leger, involves two mannequins who get married and then break up—which apparently gives the woman the hots for Joe!

Case #3 is a lady dissatisfied with her socialite existence. Her dream centers on a film whose audience is encouraged to mimic the actions of its performers (the ROCKY HORROR of its time?), and includes a cameo by its designer/scripter, the surrealist photographer Man Ray.

Case #4 is a severely agitated gangster who, once Joe manages to get him to relax, dreams of swirling shapes and scantily clad women conjured by Marcel Duchamp. The gangster ends up hauled off by a cop.

Much of Case #5 occurs while Joe is out. Its subject is an old blind man and his granddaughter, who experience Alexander Calder designed visions of shadows on a wall cast by various objects within Joe’s apartment. When Joe returns he’s given a dream (likewise designed by Mr. Calder) by the old man rather than the other way around, depicting a circus drama enacted by small wire figures.

Joe’s last “Case” is himself. This final dream, courtesy of the film’s director Hans Richter, has Joe’s skin turning green, after which he finds himself reenacting events from his past as the mythological figure Narcissus. Obstacles in this dream world include a ladder with no rungs, an ominous bloody knife (a la MESHES IN THE AFTERNOON) and a woman’s eye that appears inside a poker chip.

One is tempted to go easier on this film than it deserves, as it was clearly a labor of love made with the best of intentions. Yet the fact is surreal cinema had already reached its apex back in the 1920s, with UN CHIEN ANDALOU, L’AGE D’OR and THE SEASHELL AND THE CLERGYMAN. There are inspired moments in the present film, certainly (the mannequin wedding in particular), and it contains one asset those earlier films don’t: a rich, glittering color scheme, ensuring that even at its most irritating and low budget the film is quite pleasing to look at.

From an auditory standpoint there are many interesting touches, including the disembodied voice-overs that take the place of much of the dialogue—most likely a budgetary consideration, yet it adds a truly surreal feel—and the jazzy music of Louis Applebaum, Jack Bittner, Darius Milhaud, John Cage, David Diamond and Paul Bowles.

Offsetting the good things is the haphazard structure. It’s clear that at least five of the six dreams on display were designed with no thought to the wraparound segments, as they bear little relation to the personalities or situations of the ersatz dreamers.

But what’s most disappointing about DREAMS THAT MONEY CAN BUY is the never-varying (even in the dark-hued final scenes) tone of cloying whimsy. It’s a far cry from the shock and audacity of UN CHIEN ANDALOU, and offers ample evidence why the surrealist movement degenerated.

Vital Statistics

DREAMS THAT MONEY CAN BUY

Films International of America

Director/Producer: Hans Richter

Screenplay: Hans Richter, Joseph Freeman, Hans Rehfisch, David Vern

Cinematography: Arnold Eagle

Cast: Jack Bittner, Libby Holman, Josh White, Norman Cazanjian, Doris Okerson, John La Touche