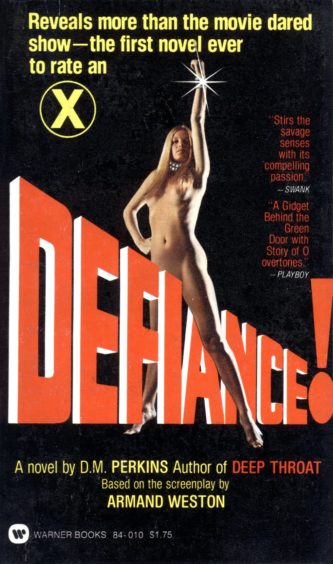

By D.M. PERKINS (Warner Books; 1976)

By D.M. PERKINS (Warner Books; 1976)

THE DEFIANCE OF GOOD (1975) was one of the better films to emerge from the golden age of porn. About an absurdly naïve young woman (Jean Jennings) drawn into a depraved S&M vortex after her parents commit her to a most unorthodox mental institution, it’s a dark, literate (the title is a quote from de Sade) and impacting piece of work that still holds up.

This novelization was written by the famed porn novelist and poet Michael Perkins. Given the dark and gritty nature of Perkins’s best-known work (EVIL COMPANIONS, THE TOUR, etc.), he would certainly seem like the ideal novelizer for THE DEFIANCE OF GOOD—which was published under the “D.M.” Perkins moniker previously slapped on Perkins’s bestselling DEEP THROAT novelization. His skills as a novelist were well utilized in that 1973 book (whose entire second half was largely invented by Perkins), and again in DEFIANCE; the front cover blurb promising that it “Reveals more than the movie dared show” is entirely correct. It’s also better written than it has any right to be, although this “first novel ever to rate an X” will assuredly never be confused with any of Perkins’s “real” books.

The protagonist is the virginal 17 year old Cathy, who after being committed to a sleazy mental hospital undergoes a dramatic transformation. She’s surrounded by sex-mad lunatics who all seem to want to manhandle her, and even more horrifying is the fact that Cathy finds herself enjoying the sexual abuse her tormentors dish out, which grows increasingly sadistic over the course of her stay. The sexual content here is far more varied—and plain gross—than that of the film, with Perkins going gleefully over the top in his descriptions of one-on-one coitus and polysexual orgies, with many lascivious details that were not in the film (such as “Mrs. Caine farted on her tongue”).

Perkins also adds an extra twenty pages onto the point where the film ends, with a conclusion that neatly sums up the story’s themes and meanings. Unfortunately, this mania for codifying and explaining has the effect of negating the film’s hallucinatory charge. The suggestion that its events may all be a dream or hallucination is bluntly negated by Perkins (with the line “No, it hadn’t been a nightmare”). The result is a text that ranks high in adults-only excess but doesn’t quite live up to the film it novelizes, nor the other work of its talented author.