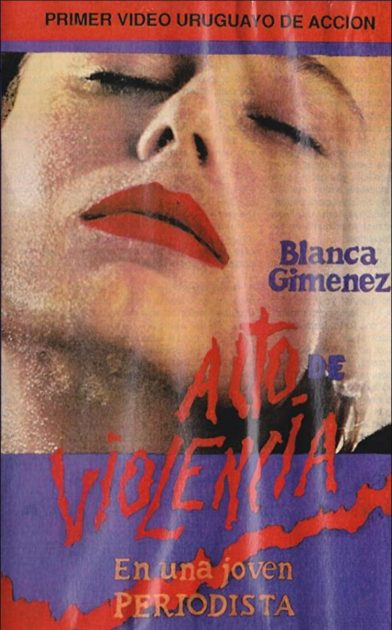

This beyond-obscure camcorder lensed 1988 feature, one of the first to receive a straight-to-video release in its native Uruguay, was given new prominence by the 2021 semi-documentary STRAIGHT TO VHS/DIRECTAMENTE PARA VIDEO. The maker of that film was Emilio Silva Torres, and the subject his fascination with ACT OF VIOLENCE IN A YOUNG JOURNALIST (ACTO DE VIOLENCIA EN UNA JOVEN PERIODISTA). Torres’ investigation, as depicted in STRAIGHT TO VHS, uncovered a network of Uruguayans as passionate about ACT OF VIOLENCE… as he, but very little data about the film’s creation.

This beyond-obscure camcorder lensed 1988 feature, one of the first to receive a straight-to-video release in its native Uruguay, was given new prominence by the 2021 semi-documentary STRAIGHT TO VHS/DIRECTAMENTE PARA VIDEO. The maker of that film was Emilio Silva Torres, and the subject his fascination with ACT OF VIOLENCE IN A YOUNG JOURNALIST (ACTO DE VIOLENCIA EN UNA JOVEN PERIODISTA). Torres’ investigation, as depicted in STRAIGHT TO VHS, uncovered a network of Uruguayans as passionate about ACT OF VIOLENCE… as he, but very little data about the film’s creation.

… given new prominence by the 2021 semi-documentary STRAIGHT TO VHS…

Finding background information on this project (which is included in its entirety on the STRAIGHT TO VHS DVD), as Torres acknowledges, is all-but impossible. The film’s director Manuel Lamas is deceased, and none of the surviving cast and crew members seem to want to speak about it. Torres tries to infer that this reticence is due to some kind of curse, although the more likely explanation is that, simply, these actors and technicians are embarrassed by the pic.

…simply, these actors and technicians are embarrassed by the pic.

It’s been likened to a student film, but I strongly doubt film student could get away with something as discordant, ill-conceived and profoundly incompetent as ACT OF VIOLENCE…. Still, there’s an undeniable fascination to it, provided one is willing to put up with a lot (and I do mean lot) of clumsiness.

The film opens with a lengthy textual scroll in which Lamas thanks his sponsors for helping make financing a reality. That explains the innumerable Coca-Cola logos flashed onscreen, and a sequence in which the lead actors enter a Wrangler outlet, where all sorts of Wrangler merchandise is lovingly paraded before the camera. As for the story, getting to it takes some doing, as the filmmaking is insanely disjointed and the tone profoundly schizophrenic—but it’s those very things, as gradually becomes clear (multiple viewings are a necessity), that give the film its Ray Dennis Steckler-like schizophrenic fascination.

Blanca is a radio reporter doing research for a report on violence in Uruguay. This entails lengthy interviews on the subject with various public officials, which Lamas plays out in real time. Dramatically offsetting this is a grade-Z subplot involving a creep identified as “Bebote” (Baby) by his mother, which whom he shares an unhealthy bond. Bebote is also determined to kill Blanca—we know this because early on in the film we see him proclaim his hatred for her via a histrionic beachfront shouting fit.

But then those two plot strands are dropped for the next 40 or so minutes. What we get in their place is a romantic interlude between Blanca and Carlos, the hunky cousin of her friend Gabriela. Blanca and Carlos’s first encounter is an unpleasant one involving a pay phone, but the two gradually warm to each other, as conveyed by a succession of on-the-town montages (including the aforementioned Wrangler plug-fest). Yet there’s trouble in the form of some Tarot cards, whose meaning, as interpreted by Blanca, portends dark things.

Re-enter Bebote, who stalks Gabriela and slashes her throat. Next he dispatches Carlos by stabbing him in the back, and then sets his sights on Blanca. She, despite being grief-stricken over the deaths of her friend and lover, allows herself to be seduced by Bebote, even though there are plenty of warning signs (such as the ultra-creepy smile he flashes when they first meet). Their courtship, as you might guess, doesn’t go too well, and concludes with a fateful confrontation in Bebote’s ominous house.

Limas’ directorial missteps are too voluminous to fully cover, but I’ll call out few of them.

Limas’ directorial missteps are too voluminous to fully cover, but I’ll call out few of them. There’s the poorly recorded soundtrack (whose dialogue is frequently drowned out by background noise), an amateurish synthesizer score accomplished by Limas himself, and visual compositions that in some scenes look thoughtfully constructed and in others like the camera was plunked down at random in the middle of a crowded sidewalk. Such discordance is fully in keeping with a film that freely utilizes voice-overs by the heroine to fill in the (many) gaps in its narrative, renders a key murder sequence for some reason in the form of a succession of still photos (a la LA JETEE), and interrupts a wholly gratuitous shot of the heroine sunbathing topless for a rumination on some birds fluttering in the air above her.

All this is enhanced in an odd way by the fact that the only available versions of this pic (whose raw materials have long since been lost) are via glitch-filled VHS transfers. That’s an entirely appropriate state of affairs given the nature of the film, which depending on one’s point of view can be viewed as a better-forgotten product of a long-since-deceased industry or an unprecedented work of demented (and most likely accidental) genius.

Vital Statistics

ACT OF VIOLENCE IN A YOUNG JOURNALIST (ACTO DE VIOLENCIA EN UNA JOVEN PERIODISTA)

Director/Screenwriter/Cinematography/Editing: Manuel Lamas

Cast: Blanca Gimenez, Vittorio Maganza, Gabriela Novasco, Carlos Reguiero, Venus Suárez