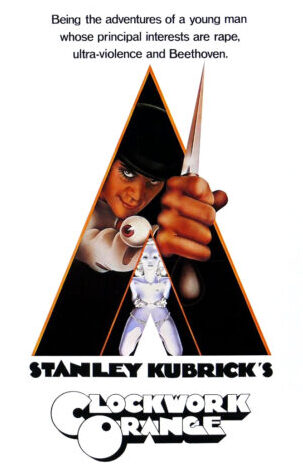

A film that was quite controversial upon its initial release in 1971 and remains a topic of enormous contention (its September 2022 bow on Netflix inspired much handwringing by establishment journalists). For that reason alone, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, the most financially successful film ever made by the late Stanley Kubrick, deserves attention, along with the fact that it’s one of the great films of our time.

… the most financially successful film ever made by the late Stanley Kubrick…

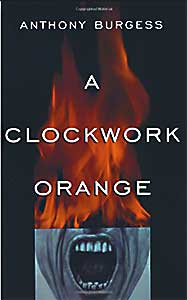

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE was based on a 1962 novel by Anthony Burgess, which he later claimed was dashed off in three weeks. That explains why, despite its impressively rendered Russian-tinged invented language—Nadsat—the novel feels hasty and under conceived. Kubrick’s adaptation (which Burgess dismissed as “a film which seemed to glorify sex and violence”) closely replicates the novel’s narrative and language, although it ignores Burgess’ non-ironic concluding chapter, in which the seemingly irredeemable teenage protagonist grows up to become a contented family man.

The film’s supposed glorification of sex and violence occurs entirely in its opening twenty minutes, in which we’re introduced to Alex (Malcolm McDowell), a young punk (aged 15 in the book but considerably older here) living in some unspecified future Britain whose décor looks suspiciously like that of the late 1960s. Alex’s principal interests are, as enumerated by the iconic poster art, “rape, ultraviolence and Beethoven.” We see Alex and his three “droog” underlings running cars off a road, beating up a bum, getting into a brawl with rival droogs, conning their way into a woman’s house to rape her and beat up her husband (a sequence taken from an actual WWII-era assault on Burgess’ wife by deserting American soldiers), and eventually turning on themselves. But when Alex accidentally murders a “catlady” (a woman with a lot of cats) during a botched break-in he’s caught by police and sent to prison.

The film’s supposed glorification of sex and violence occurs entirely in its opening twenty minutes…

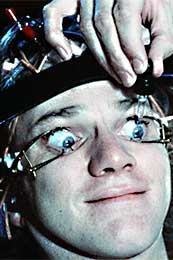

There he becomes a guinea pig in an experiment involving a serum that promises to change Alex’s criminal nature. He’s forced to view film clips involving sex and violence, with his eyelids held open by clamps, causing his reactions to undergo a dramatic shift. Before long Alex becomes violently ill whenever he sees, or commits, a violent or sexual act, and, due to the fact that the film clips are set to Beethoven tunes, has a similar reaction to the music of his beloved Ludwig van.

Upon getting released from prison Alex runs into everyone he interacted with earlier on in the film (and does so in the space of a few hours!). His parents, he discovers, have taken in a surrogate son, while the bum he beat up does the same to him, and his droog pals, now cops, further brutalize him. Alex ends up at the home of the woman he raped; she’s since died, but her traumatized husband is very much alive, and out for revenge.

That Kubrick was highly ambivalent about A CLOCKWORK ORANGE is evident in the fact that he himself was directly responsible for it being suppressed in the United Kingdom for 27 years. That ambivalence did not go unnoticed; Quentin Tarantino went so far as to claim (in an imaginary confrontation with Kubrick about CLOCKWORK) “I know and you know your dick was hard the entire time you were shooting those first twenty minutes, you couldn’t keep it in your pants the entire time you were editing it and scoring it.” For context, here’s a claim made by critic Manohla Dargis about Austria’s highbrow master of disaster Michael Haneke: “Like most art-house filmmakers who fill the screen with extreme gore and sadism…(Haneke) has tried to obscure his love for carnage with bankrupt rationalizations—it’s the audience that’s guilty and so forth—rather than just admitting it turns him on.”

That Kubrick was highly ambivalent about A CLOCKWORK ORANGE is evident in the fact that he himself was directly responsible for it being suppressed in the United Kingdom for 27 years.

Kubrick was likewise turned on by what he created in A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, although he also pushed the sociopolitical angle quite hard via lengthy conversations about free will and corporal punishment. That sense of duality extends to the visual style, marked by distorted wide angle lenses and handheld camerawork inspired by the anarchic new wave films of the 1960s that hailed from Paris, Japan, and other countries (with the major influence, according to Kubrick, being Toshio Matsumoto’s 1969 classic FUNERAL PARADE OF ROSES / Bara no soretsu), a style at direct odds with Kubrick’s famously precise and controlled aesthetic. The dichotomy works far better than it should due to the fact that the material, as laid out by Anthony Burgess, functions equally well as both a political satire and a dystopian thriller.

The actors deserve a great deal of credit for the film’s brilliance. Kubrick always had a weakness for uninhibited performers, and in Malcolm McDowell he found a collaborator who really understood the film’s tone (it was McDowell who apparently came up with the idea of crooning “Singin’ in The Rain” during the rape scene). Still, it could be argued the supporting roles are where the actors in Kubrick’s films really shined, from Timothy Carey in PATHS OF GLORY to Peter Sellers in LOLITA to Slim Pickens in DR. STRANGELOVE to Vincent D’Onofrio in FULL METAL JACKET.

In A CLOCKWORK ORANGE Kubrick corralled a number of stand-out supporting players, including the late Warren Clarke as Alex’s aptly named pal Dim, Miriam Karlin as the not-long-for-this-world “Catlady” and Patrick Magee as the writer whose wife Alex rapes. Magee could always be counted on to take things clear over the top, and was in rare form here, with facial expressions and speech patterns that might be called (highly) excessive. Such unfettered emoting can be said to camp things up, yes, but given the overall wildness of the film it also fits right in.

Vital Statistics

A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

Warner Bros.

Director/Producer/Screenwriter: Stanley Kubrick

(Based on a novel by Anthony Burgess)

Cinematography: John Alcott

Editing: Bill Butler

Cast: Malcolm McDowell, Patrick Magee, Michael Bates, Warren Clarke, John Clive, Adrienne Corri, Carl Duering, Paul Farrell, Clive Francis, Michael Gover, Miriam Karlin, James Marcus, Aubrey Morris, Godfrey Quigley, Sheila Raynor, Madge Ryan, John Savident, Anthony Sharp