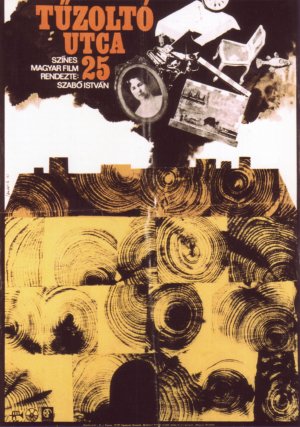

An ambitious piece of avant-garde filmmaking from early-1970s Hungary that’s both an impassioned political statement and a hallucinatory spectacle. 25 FIREMAN’S STREET (TUZOLTO UTCA 25; 1973) was very much a part of the New Hungarian Cinema, which also gave us classics like SZINDBAD (1971) and RED PSALM (1972), both of which 25 FIREMANS STREET recalls (along with the work such non-Hungarian filmmakers as Luis Bunuel and David Lynch). The director was Istvan Szabo, of the 1981 classic MEPHISTO, in one of his earliest and most ambitious features. More recent Szabo films include MEETING VENUS (1991), SUNSHINE (1999) and BEING JULIA (2004).

An ambitious piece of avant-garde filmmaking from early-1970s Hungary that’s both an impassioned political statement and a hallucinatory spectacle. 25 FIREMAN’S STREET (TUZOLTO UTCA 25; 1973) was very much a part of the New Hungarian Cinema, which also gave us classics like SZINDBAD (1971) and RED PSALM (1972), both of which 25 FIREMANS STREET recalls (along with the work such non-Hungarian filmmakers as Luis Bunuel and David Lynch). The director was Istvan Szabo, of the 1981 classic MEPHISTO, in one of his earliest and most ambitious features. More recent Szabo films include MEETING VENUS (1991), SUNSHINE (1999) and BEING JULIA (2004).

The setting is a Hungarian apartment building slated for demolition, located at 25 Fireman’s Street. Over the course of a single night the building’s residents experience a riot of dreams and memories that we perceive in a morass of reality and hallucination centering on the events of WWII.

As the film begins a woman literally swims through her room while another waits for a sleeping pill to take effect. The latter has visions of past lovers whose faces are mashed together and speak with each other’s voices. A middle aged woman, meanwhile, is ravished by a much younger man, and a young woman pines away for another tenant–who, upon entering the communal bathroom, finds himself face to face with a naked woman.

Elsewhere a group of young Nazis hold a meeting and an old man finds himself tasked with taking care of a roomful of screaming babies, just as a snowfall occurs inside the building. A wedding reception is held in one room and a birthday dance in another, while soldiers stage war drills in the courtyard and Barbie dolls parachute down from the sky.

From there things grows appreciably darker as a woman commits suicide by throwing herself into the courtyard, and a mass round-up takes place in which the buildings’ residents are stripped naked and deloused. In the process one of the tenants is forced to admit she harbored political dissidents during the war as people are hung in the street outside the building and gunfire is exchanged by anonymous combatants.

In relating this authentically dreamlike reverie, which follows no narrative conventions of any sort and demands a fair amount of attention on the parts of viewers, Istvan Szabo utilizes every conceivable cinematic technique. Characters frequently break the fourth wall to stare into or directly address the camera amid whiplash tonal shifts, as when an emotional death scene unexpectedly segues into a straightforward depiction of a doctor bitching about his compensation. Sound is also utilized quite effectively in a layered and complex audio-scape whose most striking component is, unexpectedly enough, silence.

The cinematography by the great Sandor Sara is another indispensable asset. Sara’s work on Zoltan Huszarik’s SZINDBAD is legendary, and the painterly visuals of 25 FIREMAN’S STREET are nearly as strong, being a pivotal component in the film’s hallucinatory aura.

The one major sore spot? None of the characters are especially interesting, a fact exacerbated by the fact that most of the cast members look alike. But then, in-depth characterization evidently wasn’t among Szabo’s concerns. Rather, he was attempting to convey the troubled psyche of his country, irreducibly scarred by the Nazi occupation of 1944, in the form of an extended dream. A lofty ambition, certainly, and one Szabo doesn’t entirely pull off, but he does succeed in creating a wholly unique and confounding piece of cinema.

Vital Statistics

25 FIREMAN’S STREET (TUZOLTO UTCA 25)

Budapest Filmstudio/Hungarofilm

Director: Istvan Szabo

Screenplay: Luca Karall, Istvan Szabo

Cinematography: Sandor Sara

Editing: Janos Rozsa

Cast: Lucyna Winnicka, Margit Makay, Karoly Kovacs, Adras Balint, Erzsi Pasztor, Edit Lenkey, Ervin Csomak, Janos Jani, Zoltan Zelk